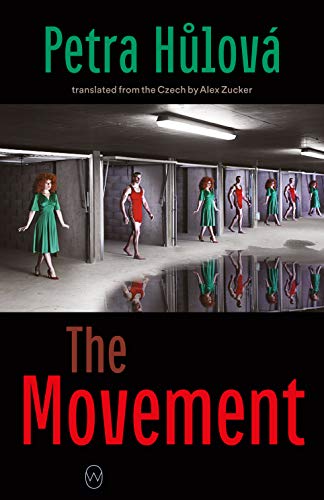

THE MOVEMENT

Today is the first Wednesday of the month, open-door day. I show the visitors around—women, married couples, and men (more and more older bachelors are now entering treatment of their own free will)—to the canteen, the classrooms, the client dorms, and if anyone is interested, I also take them down to the solitary confinement cells. Back when the Institute was a meatpacking plant, the basement rooms were used to store preservatives, barrels of flavoring, and spare parts for the conveyor belts—all nonperishable items immune to the damp, which clients tend to complain about after their second, third, or fourth month locked away. We sympathize with the fact that it’s damp, but not with the complaints, since there are reasons why the men are sent to solitary, and those reasons are reviewed by at least three people—section head, doctor, and guard—as well as the nursing staff.

“My Míša would go out of his mind in here,” says a long-legged blonde as I give her the tour. Her knees nearly buckle as she peeks into one of the two cells, both currently vacant, and even though just a moment ago, when I took her through the garden, she was ready to send her husband here next week, it looks like now she’s starting to reconsider.

“You said he suggested you get breast implants, which would mean he qualifies for the maximum stay with us.” I wonder which illegal clinic he wants to send her to, the lout, since external cosmetic modifications have been illegal for at least five years. Manhood Watch has spent those years bemoaning the fact that procedures now take place in unsanitary and unprofessional conditions (with women being crippled at clinics run by unlicensed doctors out to make a quick buck), but in the Old World, when doctors screwed up a woman’s plastic surgery nobody gave two hoots, and what else was a plastic surgery clinic but the Old World in a microcosm.

After the Interior Ministry basement, the second place Rita bombed was a plastic surgery clinic, without hesitation, and I say without hesitation because she blew it up just three days after the ministry. The whole country was gripped with panic. Out of fear for the safety of their employees, most clinics “interrupted operations” within a few days. The doctors just stopped going to work.

“But I’m the one who wants them,” the woman replies as I relatch the basement door (my smart card’s acting up again). We head up to my office, then I dash out and a minute later come right back with coffee. One for me, one for her. I know from experience the conversation will take at least an hour. An hour for me to convince her, plus another till she signs the papers. And if you asked me what percentage of women who come to the Institute to have their men interned end up in facilities themselves, I would say fifteen plus. Community Centers is what we call the treatment facilities for women.

“It’ll give you a chance to relax, Mrs. Ptáčková,” I say, handing packets of sugar across the desk. I don’t intend to hide anything, it’s solely up to her. “While your husband is here being treated for his addiction to porn, you can rid yourself of your addiction to makeup, the ideal of the Old World figure, and your obsession with the size of your breasts,” I say as she stirs sugar into her coffee.

I figure she must be from the countryside. It’s the only way to explain how she’s been getting away with her illegal behavior. In some rural areas, the Old World is still hanging on, tooth and nail. I know from the media as well as from my colleagues, who passed through several villages on their way to the capital for the anniversary of Rita’s speech in Europarliament.

“The world doesn’t look at you—you look at it.” I choose my words carefully. It’s important not to moralize, or she might be scared off and not even bring us her husband. Choosing the right words in the midst of so many prejudices is like walking through a minefield. But introducing the New World in a way that will appeal to a woman with no education, you have to forget finesse and take the blunt approach: “For starters, there’s nothing wrong with pigging out on sweets,” I say. Suddenly Mrs. Ptáčková is all ears.

“With a figure like yours, you can do whatever you want. Once Míša completes his reeducation, the only thing that will matter to him is what you’re like on the inside. Your true self, the richness of your soul, the way you relate to each other. Which means you can finally grow old without worrying, and eat whatever you want, as long as you keep an eye on your health. But that’s purely up to you.”

The blonde stares silently into her coffee.

“Every Community Center program includes wellness procedures and field trips. The one I’d recommend to you is next to a preserve with natural mineral springs …”

I remember my own visit there several years ago. The paths in the adjacent park where the residents went for walks between procedures were lined with a rare variety of orange tulips (reportedly a gift from a donor in the Netherlands).

“Does wellness include cosmetics?” asks the blonde. “I’ve been considering permanent makeup,” she adds, and I wonder what kind of backwater she must be from to be thinking about getting something that years ago women in cities paid good money to have removed, and whether diversity is really the right word to describe the diametrically opposed situation between cities and rural areas, or if it’s time to bring the term “two-speed Europe” back into style.

In the end we agree that Mrs. Ptáčková, like so many others, will attend the Community Center on an outpatient basis. The Movement has no desire to drag women away from their children, especially not nowadays, when thanks to our efforts their interest in giving birth has increased.

I think what finally tipped the scale was my comment about her husband’s young female coworkers, whom she mentioned in passing, setting me up for the smash: “After his stay at the Institute, he won’t pay any attention to those girls at the front desk anymore—that I guarantee.”

Hearing those words, it was like a weight lifted from her shoulders, and when I told her again that she could eat whatever she wanted, and that the Community Center offered an all-you-can-eat buffet 24-7, she was practically in the bag. Especially when she revealed that the main reason she wanted to get her breasts enlarged was because of the girls at her husband’s job.

“You really think he’ll still love me when I’m old?” she asked skeptically. It was as if she had slept right through the last decade. She insisted on showing me the bags under her eyes, “to make me understand.” She smiled when I told her we didn’t have any mirrors. That clinched the deal. After two hours in my office, she walked out in a state of elation.

“I’ll drop him off on Wednesday, I promise, right after work.”

PETRA HŮLOVÁ’s provocative novels, plays, and screenplays have won numerous awards, including the ALTA National Translation Award for Alex Zucker’s translation of her debut novel, All This Belongs to Me, and she is a regular commentator on current events for the Czech press. She studied language, culture, and anthropology at universities in Prague, Ulan Bator, and New York, and was a Fulbright scholar in the USA. Her eight novels and three plays have been translated into thirteen languages. She used to define her writing as “3G”: always working with topics of gender, generations, and geography. Her novels are often narrated in first person and range from intimate confessions to buoyant epic sagas. The Movement is her latest work.

About the Translator:

ALEX ZUCKER’s translations include novels by J. R. Pick, Jáchym Topol, Magdaléna Platzová, Tomáš Zmeškal, Josef Jedlička, Heda Margolius Kovály, Patrik Ouředník, and Miloslava Holubová. He has also translated stories, plays, young adult and children’s books, essays, subtitles, song lyrics, reportages, poems, and an opera. His translations of Petra Hůlová’s Three Plastic Rooms and Jáchym Topol’s The Devil’s Workshop received Writing in Translation awards from English PEN, and he won the ALTA National Translation Award for Petra Hůlová’s All This Belongs to Me. He lives and works in Brooklyn.

Read more work by Petra Hůlová:

Fiction in B O D Y

Interview in Project Plume

Fiction in Words Without Borders

Interview in Literalab