THREE PLASTIC ROOMS

(an excerpt)

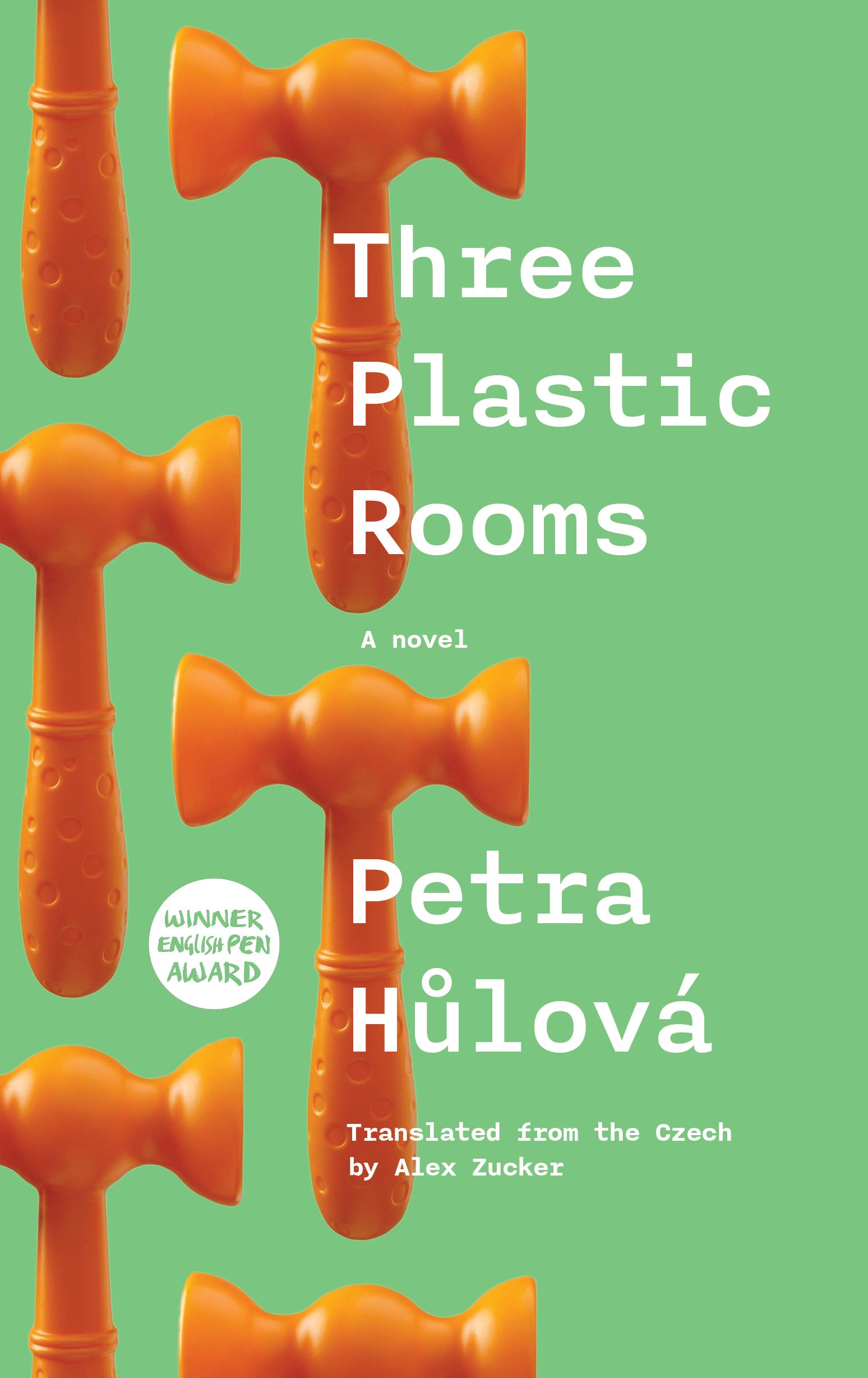

Three Plastic Rooms

A novel by Petra Hůlová

Translated from the Czech by Alex Zucker

Published by Jantar Publishing

TV Episode One: Women With Handbags

I wonder if anyone ever gives her a grinding down to the bone? That one there, who doesn’t take care of herself and stuffs her face with whatever she feels like. I wonder if her slit too is like a peephole into a lobby with a blown-out lightbulb, a long dark narrow hallway that can turn supple and slicken, and tighten and choke like elastic on a pair of panties? I wonder whether hers does that too? I wonder if she knows how to strangle a snake until it turns red, to take hold of it by the throat and give it a proper yanking? Because if she did, she would have no reason to take care of herself anymore, and wouldn’t have to worry that her makeup was expired, crusty, and peeling off in strips like the damp plaster of the building where she sits out every day.

I see her when I walk past. Out there on the corner, where the overhang makes for a cozy feel in spite of the piss that rains against the wall every night from the men who think that nobody can see them in the dark and that no one will come walking by at such a late hour. Her hair is short and her fat face is covered in red spots, but they aren’t pimples. She just scrubs her face too hard before she goes out. I don’t think it helps.

I wonder if any man has ever turned to look at her out of sheer eagerness, and decided to choose her because she has something to give? Probably not, or she wouldn’t be sitting there so downcast every morning, looking like she was waiting to be rescued.

Some women hardly take care of themselves at all. They get fat and think no one will notice as long as they dress in loose-fitting clothes. I suppose that no one has ever told them high heels aren’t for comfort, you wear them to make your legs look slim. Women like that don’t walk the streets, much less strut them. They plod along the sidewalk like they were wading through leafsludge in a neglected city park, and they may think that it’s all the same, but it’s not.

Don’t stink and watch your weight. Those are the most important resolutions I know of. Every morning I plop myself down in front of the mirror and stare into my face, just in case it might finally tell me something I don’t know. It stares right back, as if expecting the same from me. We’ll never settle anything doing it like that, but still, every morning I try just the same. Maybe one day it will give in. Sometimes it looks like a wisp of myself. Smirking at me with the innocent grin of a bird. Then again, other times it looks like it was slapped together from rags, like a hastily stitched soccer ball, and it’s asking for a kick, too, and all this in the time it takes us to reach a lasting agreement. Meanwhile the stool has imprinted a square into my rear and I can feel parts of my own edges, the ones that don’t hold together too well, overflowing the stool’s edges, even though I’m not overweight. It’s always lovely to have your day get off to a cheerful start.

If I had a courtyard, I would sweep it from corner to corner using a birch broom I bound together myself, and every time I did my chores, I would feel like one of those women at the country fairs who dress in traditional folk costume. Not like in the room where I wake, occasionally with a man at my side, surrounded by molded plastic. Including my little yellow molded-plastic bird, though its cage is metal, just like a real bird’s. I take great joy in the ingenuity of human invention. Everybody’s little yellow plastic bird is the same, pumped out of a machine in the far reaches of China, and so even if it was produced by child labor it still bears a whiff of the distant lands from whence it came, no matter that it flew on the wings of a Boeing.

At least it will never abandon me for warmer climes in Africa. I already get sad every fall as it is, when the birds begin to disappear. They roost even though no one forces them to, which takes some real self-discipline, so I wave at them from the street, and at least in that small way I share in their concerns. Apart from that, it doesn’t mean much in my life, I’m not the depressive type. Never have been. Some might say disorderly house, but I call it a human nest, filled with warmth and cozy corners hiding all kinds of surprises. Including the used tissues that fall behind the bed when I squirm too much at night. I slip them under my pillow after I blow my nose, and I’m not sure if they have retractable legs, or maybe more like cat’s claws in tiny little sheaths, but somehow or other they get down there, and within a few weeks they’re nice and hard. Then later, when I try to smooth them out, they crackle like the radio, or the way the radio would crackle if it weren’t e-.

The e-world plagues me, it makes me feel I’m not fast enough, even if I am still young and hairless and need warmth and caressing to blossom like the flower that every woman is, and nowadays men are flowers too and also need to be cared for. So much work goes into caring, and the labor force for it is lacking, and that’s why it’s so important for our labor market to be open to outsiders, who aren’t yet exhausted by the ups and downs of daily life, though it’s true they don’t take such good care of their looks, which puts them at a bit of a disadvantage on our streets. But flaws are part of the e-world too, since otherwise there would be nothing to improve upon, and large-scale industry would wilt like a lily.

The cheap manpower is what I like best, when they stand in the street, sunning themselves, leaning on their shovels, sweat beading on their dark, firm arms. I’m sure they could use a back massage, but they won’t come out and say so. Instead they just stand there puffing away, hiding inside a cloud of tobacco smoke, though they could easily hold their own in any local bodybuilding contest. And of course, if you’re a bodybuilder, massages come with the territory. Muscles need to be kneaded in order to remain supple yet still be pumped enough for the audience in the back rows. But I just walk right past those men with the shovels, sunken in manholes up to their waists, just as I do past the fat woman with the short hair on the corner, my brain just quietly kneading the little marble of my thoughts.

Years from now, when my periods stop, and I sweat like a dog even in winter, I’ll have to trade in my purse for a proper handbag to make sure that I have enough room for a backup supply of blouses. I can carry the weight, and it might help keep my body firm, assuming that anyone still cares about it by that point.

These are the kinds of mysteries that deserve a special TV series all their own. A series illuminating the little mysteries of life that we otherwise dismiss. Are we all really just stationmasters waving our signal discs up and down, traffic police directing motorists in a traffic jam? Let them go right on waving their arms along with the rest of the idiots while I fill the gap in the market, since we don’t have an educational series like that yet. The whole thing’s my idea, I came up with it just now, and I promise, I’ll be thinking about it the whole time, from here on in. You’ll see how well suited to teamwork I am. I’ve got ten people I can count on every finger, at least on some days of the week.

____________________________________________________________________

PETRA HŮLOVÁ’s novels, plays, and screenplays have won numerous awards, and she is a regular commentator on current events for the Czech press. She studied language, culture, and anthropology at universities in Prague, Ulan Bator, and New York, and was a Fulbright scholar in the USA. Her eight novels and two plays have been translated into more than ten languages. Three Plastic Rooms is her second novel to be translated into English after All This Belongs to Me (2009).

____________________________________________________________________

About the Translator:

ALEX ZUCKER (b. 1964) has translated novels by Jáchym Topol, Petra Hůlová, Patrik Ouředník, Heda Margolius Kovály, Tomáš Zmeškal, and Magdaléna Platzová. He is winner of an English PEN Award for Writing in Translation, an NEA Literary Fellowship, and the ALTA National Translation Award. In addition to translating, he has worked in journalism and human rights. From 1990 to 1995 he lived in Prague, and he currently lives in Brooklyn, New York.

____________________________________________________________________

Read more work by Petra Hůlová:

Fiction in Words Without Borders

Interview in Literalab

Essay in The Guardian