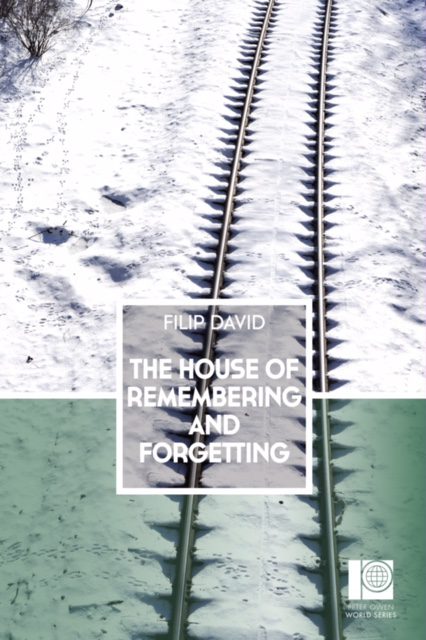

THE HOUSE OF REMEMBERING AND FORGETTING

(an excerpt)

The House of Remembering and Forgetting

A novel by Filip David

Translated from the Serbian by Christina Pribićević-Zorić

Published by Istros Books

In which a mysterious event is described but nothing is explained. Everything is in doubt, including life itself

It was two o’clock in the afternoon when the telephone rang.

‘Albert Weisz?’

Holding the telephone with one hand, I wiped the sweat off my brow with the other. The rasping, chilling voice had been calling for the past few nights, always at the same time.

‘Yes, this is Weisz.’

‘Bertie,’ said the stranger. That’s what my mother used to call me, but she has been gone for a long time now.

‘Who is that? Tell me. What do you want?’

No answer. The person at the other end of the telephone was silent. And then he hung up, as he always did when questioned.

Who is it that keeps disturbing me at night? Where is he calling from and why? I could not picture a face to go with that voice. Who is it behind that cold, metallic voice that has something unhuman about it? Maybe it is a voice straight from the grave. Why not? Technology is so advanced these days that anything is possible. Whoever is calling is certainly doing so for a reason. Does he suffer from insomnia like I do? But that is no explanation. It would be insane to think that these late-night calls have no purpose. Of course, that, too, is possible. The world is full of lunatics, and disturbed people are guided by their own mad ideas.

Such troubling thoughts give me insomnia. I amble around like a sleepwalker, put the water on for coffee, and as I wait for it to boil I step over to the window and peek out through the curtains at the deserted street. For a long time now I’ve had the feeling that I am being followed. And there, in the doorway of the building across the way, I spot the spy. He is hiding but his shadow gives him away. Who is he working for? Maybe he belongs to a secret neo-Nazi organization? Insufficient evidence for the police: just as it is impossible to place that rasping voice on the telephone, although its owner is obviously calling for some reason, so this spy is momentarily merely a shadow, or, rather, the shadow of a shadow, invisible yet present. I reported it to the nearby police station, and they wrote it up, but the good gentlemen did not take my complaint seriously. The police receive complaints of this nature every day from people of a certain age prone to fantasizing.

All the same, I found my visit to the police station and their lack of concern upsetting. I came out barely holding back my tears. I was deeply, truly humiliated that the police officer did not believe me. I’ve been enduring humiliation on a daily basis for a long time now.

I was not supposed to have survived. That’s the problem. It was not planned for me to survive. I often talked about it with Solomon. We were connected by age and fate. Scientists had announced the discovery of a new particle, known as the God particle. The exciting findings of a decades’-long ‘hunt’ for a particle that could help humankind understand the birth of the universe were announced at a press conference, and they attracted a lot of international attention. But both Solomon and I, each in our own way, had been searching for the God particle that explained evil.

Solomon Levy was one of my few surviving friends. He’s gone now, too. His death was a warning. But who cared about that? The papers merely carried a small, barely noticeable item saying that a senile old man had caused a fire in his flat, probably out of negligence, and that the place had been full of old papers and books. He alone was to blame for having been burned alive and enduring such a terrible death. The on-the-scene reporter wrote that the spacious three-room attic apartment was an absolute dump, crammed from floor to ceiling with old newspapers that the old man had collected, probably with the intention of selling them, so, when a cigarette end or cigar fell on them, it started a fire of catastrophic proportions. So many falsehoods in just a few lines of reporting. Solomon Levy did not smoke; anyone who knew him knew that, and the ‘old papers’ that the reporter describes were an important, indeed the most important part of his life’s work: his collection of writings about the many forms of evil, from the Holocaust to the daily chronicles of crime. My late friend Solomon Levy could be described as a researcher. He was a diligent, devoted archivist of everything published on the subject of evil. He was collecting material for a comprehensive book he wanted to write about the criminal aggression that lies behind a wide range of behaviours, about different manifestations of wrongdoing and madness. I helped him to collect and classify this material. We met every day, trying to identify patterns that would give us a lead. It was our obsession, you might say. Day after day, crimes occurred that were so monstrous they defied the imagination:

Son kills sleeping father. Newborn baby drowned by mother and dumped on rubbish tip. Man sets vicious dog on neighbour and tosses corpse in well. Ninety-year-old woman raped by drunkard. Entire family murdered in moment of madness. Violent clashes between fifteen-year-old boys. Pathologically disturbed people organize fights between boys that they treat like dogs. Young man confesses he just killed a man and drank his blood. Killer paid by a local drug cartel and terrorizing Mexico is only twelve but has already murdered dozens of people. Polish woman stabs seven-year-old son and five-year-old daughter more than 150 times ‘because there is evil in them’.

Over a period of just a few days there were lots of news items like that. No wonder Solomon was buried deep in newspaper clippings and articles. All these routine yet bizarre cases will be properly interpreted and explained once we find a mathematically reliable way to identify what they all have in common, what lies at the heart of such incidents; once we discover the actual ‘seed of evil’, the God particle we are looking for.

In the margin of an article about war crimes, my dear Solomon had quoted a poet who said that since time immemorial ‘killers of all nationalities have belonged to but one nation, the nation of killers’ and that ‘everywhere the children of light and the children of darkness have already separated’.

A few days after the fire and Solomon Levy’s funeral at the Jewish cemetery, I decided to go to the apartment of my deceased friend. I had the keys to his place just as he had to mine. We had both been on our own and had agreed to help one another if necessary. But even with that key I could not help Solomon Levy any more.

Like a thief, which is what I was, I practically tiptoed up to Solomon’s attic. The police had put up a No Entry sign. The stench of burning pervaded the corridor. Traces of the fire were everywhere.

I had an irresistible urge to see my friend’s flat one last time; we had spent so many long hours talking there, having conversations that were very important to us. But the flat no longer belonged to Solomon, and I was afraid that I might be stopped and asked what I was doing there. Having barely managed to unlock the crooked wooden door, I stepped into a room that was unrecognizable. All you could see were the blackened, sooty rafters and charred pieces of furniture strewn around. Nothing worth mentioning was left, just the remains of a place where someone had once lived, traces of someone’s life. Miraculously, a stack of papers written in Solomon’s hand had survived. The flames had devoured everything but not this one pile of paper. I remembered the famous saying that manuscripts do not burn. Was it the Devil who said that or somebody close to him? Anyway, that was all that remained of our friendship. I had the right to take what had escaped the flames. But the moment I touched the sheets of paper they disintegrated into powder and ash. If these writings had ever held the unsolved secret of the origin of evil, that secret was now destroyed, and all our hopes and efforts to trace it were lost.

I hurried away from the place where my friend had so tragically died. I could not shake the uneasy feeling that an all-seeing eye was constantly watching me. Did it belong to the person who hounded me late at night; was that the reason for my long, troubling hours of insomnia?

Night was falling. The city lights went on. Everything now had its shadow: the trees, the houses, the few passers-by. My own shadow followed me, fear followed me; something in the darkness said, ‘You can run, but you cannot escape!’

____________________________________________________________________

FILIP DAVID (b. 1940, Kragujevac) is one of Serbia’s pre-eminent cultural figures. He is the author of three novels, four short story collections, in addition to several collections of essays and a long career writing for film and television. His stories and novels have won many prizes, including the Mladost, Milan Rakic and BIGZ awards, the Prosveta Prize for book of the year, and the Ivo Andric Prize. His books have been translated into several languages. His short stories are included in more than twenty anthologies. For The House of Remembering and Forgetting he was awarded the most prestigious Serbian literary prize, the NIN Award, for the best novel in 2014, and the “Meša Selimovic” Award for the best novel in the region of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Serbia and Croatia. Filip David lives in Belgrade.

The House of Remembering and Forgetting is being published by Istros Books and Peter Owen Publishers in October 2017.

____________________________________________________________________

About the Translator:

CHRISTINA PRIBIĆEVIĆ-ZORIĆ has translated more than thirty novels and short-story collections from Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian and French. Her translations include the award-winning Dictionary of the Khazars by Milorad Pavić – as well as Pavić’s Last Love in Constantinople for Peter Owen – and the international best-seller Zlata’s Diary by Zlata Filipović. She has worked as a broadcaster for the English service of Radio Yugoslavia in Belgrade and for the BBC in London and was the Chief of Conference and Language services for the UN International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia in The Hague.

____________________________________________________________________

Read more from Serbian Fiction Week:

Fear and his Servant by Mirjana Novaković