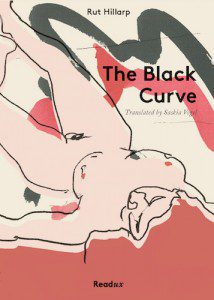

THE BLACK CURVE

The Black Curve

The Black Curve

A novel by Rut Hillarp

Translated from the Swedish by Saskia Vogel

Published by Readux Books

It’s true, I didn’t come. I never intended to. And I can’t accept the discreet excuse you offered me in your letter.

I don’t believe you waited long enough for me … I asked for you to wait as a period of gestation during which your desires would consolidate, your emotions coagulate. Until now any man has been able to satisfy these desires in you, but after this waiting period, they will be devoted only to Man.

Because waiting shapes his story and gives him his reality …

Like hunger, waiting is creative. It rouses new senses and needs, and so it offers Man an infinitesimal keyboard and a palette with metaphysical resonance.

Waiting entices the desired man, and he comes more quickly when he is late than when he is on time.

. . . . . .

In the laboratory of waiting, woman is subjected (on a smaller scale) to the great torments of her union with Man. In the retort of impatience, in the test tube of confusion, in the oven of suspicion, her primary elements are distilled, reconstituted as raw material for original sin. And she places her clay still soft and wet in my hands, in the creative hands of Man.

. . . . . .

But upon receiving your letter I’ve decided that it’s time for me to come.

And I will come tonight.

I place this letter here under my cigarettes.

Tonight.

No, I don’t believe it. I no longer dare to believe. Like so many times before.

His wording. I know him inside and out. Scientific love. He uses language to make an impression, not to communicate. It’s pure luck if he happens to be telling the truth.

I’ll hang up the blouse, anyway.

“Man”! Delusions of grandeur. If it weren’t for that voice. Irony so piercing the air seeps out. He twines his irony with affection, so you can never tell where he is.

Leaving the mind to spin.

The black or the red robe? I’ll buy a blue one next time.

Has this been anything but illusion and waiting and disappointment?

Has it?

I smoke too much now. Even though I never buy cigarettes. They’re always on the night stand.

But I don’t want to go through this again. Not any of it. No, I refuse.

He wrote to me using the formal “you”! I smoke too much now. “Others would’ve given their lives and all their earthly possessions for a night like this, and all I give you are a couple of cigarettes,” he said. I didn’t know there were only two left in the etui. If not for her, they would’ve just laid there — idiotic souvenirs — I wasn’t available that night anyway. His voice a wonder. “But you’re … You frighten me.” He stood by the bed, pulled the curtain aside so he could see my morning. And his face, renewed, distant, resting in its own myth. It doesn’t speak to me anymore. But when she smoked my cigarettes, then I understood that he had acted the same with her. Until that point I had felt nothing but pity for her, I didn’t believe in retroactive jealousy. “You’ll get the cigarettes back tomorrow.”

But he didn’t stay and smoke them with me. He never smoked, not even at dawn. He stood in the doorway. I ventured:

— You do love me a little, don’t you?

— It’s far worse: I haven’t had my fill of you yet.

He stood in the doorway with his hand on his hip dressed all in gray, wide-cheeked. How old could I have been. Dad poured disinfectant on my wound. I don’t remember what that man was called, but he drove a car and played ball and was standing in the stationery shop. All that he left behind was his posture (I tried to mimic it in photographs) and the disinfectant.

I suppose he could be counted as part of my harem.

Along with all the Heroes and all the others that were you.

The little cottage in the forest that could only be found by the man of the evening. And why did I have to be hung from the ceiling, by my wrists: but that’s how it was, that’s how I recall the scene with the long whip. That was all that happened.

Little Isaac so pious and innocent in the large family Bible, his arms bound behind him. Father knows best. The knife in Abraham’s sentimental hands. The angels and the rams have disappeared.

I didn’t really like Abraham and Isaac — they were innocuous. The scenario was what appealed to me.

Awaiting fire and knife.

____________________________________________________________________

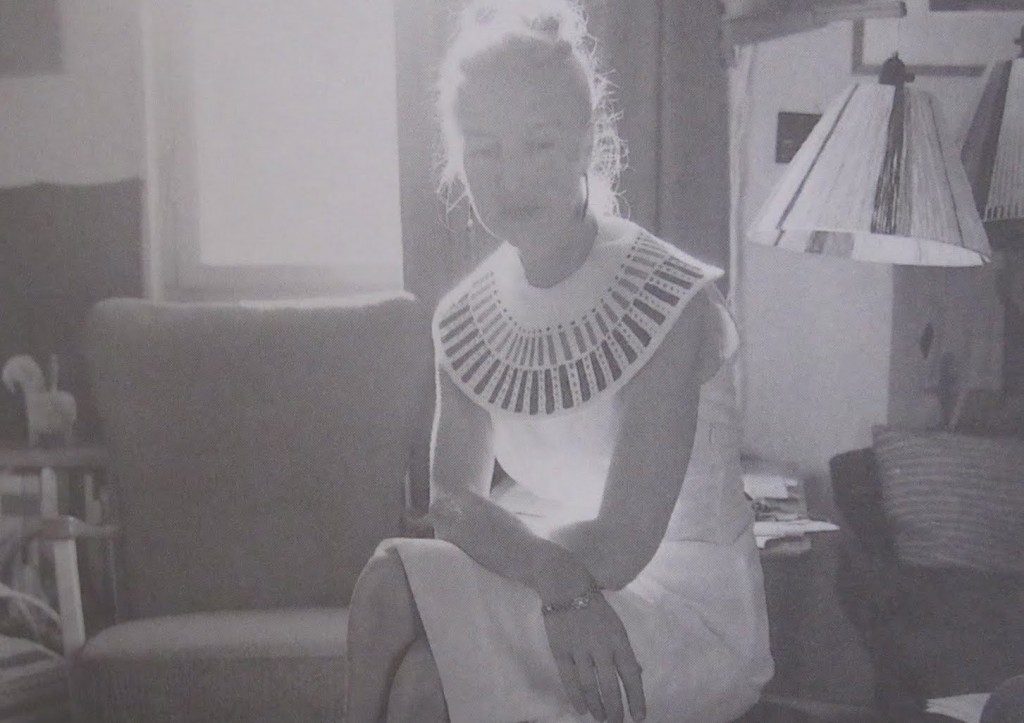

RUT HILLARP (1914–2003) was one of Sweden’s great lyrical modernist writers, an “erotic genius” investigating dark love, power, submission, and the female subject. The Gothenburg Post called her “the grand old dame of the women’s movement” and her erotic experiments have been compared to Anaïs Nin’s. In addition to writing prose, she was a poet, a passionate diarist, a teacher, a photographer, and filmmaker. The Black Curve appeared in her first novel and the publication of this extract marks the introduction of one of the great Swedish modernists to the English-speaking world.

The English translation of The Black Curve is being published October 26, 2015

____________________________________________________________________

About the Translator:

SASKIA VOGEL is a translator from Swedish and German. Her stories have appeared in The White Review, The Erotic Review and Zocalo Public Square. She is currently completing a novel with the working title I Am a Pornographer. She blogs at saskiavogel.com.