____________________________________________________________________

Read Marvin Bell’s Wednesday

____________________________________________________________________

Marvin Bell’s poem “Wednesday” is the anthem of every working poet. It first appeared in the New Yorker on October 27th, 1986. I was eight years old at the time, living in the desert farming town of El Centro, California, on the US-Mexico border. I had no idea, as Philip Levine says, “what work is”. It was not until I learned what work is that I discovered why poetry matters. It was not until I had suffered that poetry became necessary.

America was just emerging from a recession, and El Centro’s unemployment was among the highest in the nation. The real economy on the pre-NAFTA border was not farming, of course, but drugs. Where there are illegal drugs and poverty, there are gangs. Even the teachers at my high school knew which gangs “owned” which parts of campus. I learned to watch my step.

One such teacher, Jesuit-educated into a zeal for the Great Books, introduced me to two survival skills: humour and poetry. Although there was little water in the Sonoran desert, there were plenty of mirages, and I can still see my wavery teenage self, as Bell put it, “holding above still puddles / the books of noble ideas.” These books carried me out of El Centro, into university.

There I learned about poetry, but it was not in hallways of lofty institutions that poetry became food for my hunger and water for my thirst; it was instead somewhere that I never thought I would find myself—in the neonatal intensive care unit of a hospital, holding my infant son in my arms for the very last time.

After that, all my worldly ambition evaporated. Some days, I didn’t know how I was going to get out of bed, let alone go to work.

It was then that Bell came to me, with that gorgeous Blakean oration of a first stanza, everything sodden, downward, washed in grey—as even my own vision had seemed to have been switched to black-and-white, “The Wizard of Oz” in reverse. But then, like the visions of angels William Blake saw as a child, “the palpable Sublime flickered as motes on broad leaves.” The “Higher Good” and “Greater Good” contended as sap on bark and the “truly Existential … loitered famously in the shadows as if waiting for the moon.”

Poetry came to me, like it comes to Bell in this poem, as the inkling of something magnificent and otherworldly amidst the everyday drudgery of mundane living. Poetry became the only language that made sense to me. I got up before dawn to read and write, because poetry gave me a reason to throw off the body-warm quilt and face the day.

The earlier moments I had experienced, head-down in a book walking home from school through the bad side of town, returned to me with the vehemence of a holy avenging angel. Poetry sought me out, and dared me to go on, flaming sword in hand.

I carried poetry books with me like talismans, but more importantly carried this kind of burning secret knowledge, a world-within-this-world. As Bell says, “Like you, / like anyone, like the rumoured angels of high office, / like the demon foremen, the bedevilled janitors, like you, / I returned to my job — but now there was a match-head in my thoughts.”

Since reading that line, I have never looked at the inherent potential in the head of a match quite the same way again. Nor have I seen so perfectly expressed, through the materials of everyday idioms, how books can be a lifeboat, buoying us up. They hold us aloft, even as we hold them up to the flickering light in a passenger train at the end of a long commute.

It is the everydayness of Bell’s constructions that infuse the sublime with the ordinary, and in doing so, infuse the ordinary with the sublime. Like Clarence Odbody from “It’s A Wonderful Life”, Bell’s “angels” have dirt under their fingernails, and road dust on their shoes. Ordinary words, pressed into extraordinary constructions, take on a meaning of their own through the music of everyday speech: “lit by nothing but mind-light, I saw that the horizon / was an idea of the eye, gilded from within, and the sun / the fiery consolation of our nighttimes, coming far.” The fiery consolation—at once aflame and soothing—poetry, in its necessity, sought me out in the darkest of nighttimes, coming far.

These two blocky stanzas, each only half a page but hefty with syntax, feel durable and confident in what they proclaim, a durability that I craved. They speak boldly of the ephemeral, of “colours visible to closed eyes” and “knowledge gathered that could not last the day.” Cast into transience, with no sense of ground beneath my feet, this celebration of the perishable and indescribable (in words, no less) became far more real to me than the emails piling up in my inbox, or the pavement underfoot.

The other survival skill that I learned in the borderlands is present here too—if not outright humour, at least her cousin, whimsy. After witnessing the truly Existential “loitering / famously” like a figure from an Orson Welles noir film , Bell tells us, “All this I saw in the late afternoon in the company of no one.” Being alone among the mysterious is wry, of course, because there are no other witnesses, and nobody will believe you. The “company” kept here is entirely one’s own, something I came to enjoy increasingly, even learned to cherish, as a budding writer.

Later Bell muses that this expectant air was “carried by—who knows?—the rhythmic jarring of brain tissue…” This interjection—“who knows?”—comes off casually, a Gallic or Yiddish shrug, a gesture of respect to the unknown and the unknowable. It could be science. It could be something more. Nescience, not knowing, is as much to be celebrated as anything, because it is part of how it feels to be alive.

There are mysteries in this poem, even as there are mysteries wrapped up in the quotidian and the banal. At a time in my life where nothing made sense, least of all my everyday routine, this little poem did more than just make sense to me. It felt right, with its strange music and off-kilter observations, in a manner beyond what my scholastic education allowed me to articulate. This transposed into a way of sensing, observing, and being in my life that allowed me to start writing poems again—something I had quit outright (because that’s what I thought adults did) in anticipation of fatherhood.

The long days were still long days, and the sometimes the dark nights seemed truly star-less. “But now, there was a match-head in my thoughts.” Not lit, mind you, but present. The ordinary was still an effort and, as Andy Warhol famously quipped, “They always say that time changes things, but you actually have to change them yourself.” I changed through reading and writing, one day and one line at a time. I kept swinging my feet out of the covers, onto the floor.

I am grateful to this no more than thirty-line poem for saying what I didn’t even know needed to be said. It ordained me into that class of working poets for whom reading and writing are as important as breathing in and out. Now I know of whom Bell speaks when he says at the end of this poem, “it would not be until quitting that such a man / might drop his arms, that he had held up all day since the dew.”

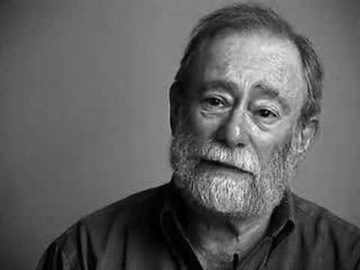

— Robert Peake

____________________________________________________________________

ROBERT PEAKE‘s poems have appeared in a wide range of journals and anthologies including North American Review, Poetry International, Iota, and Magma Poetry. His essays and reviews have appeared in Poetry International, the Chicago Sun-Times online, and The Huffington Post. His poems have also received commendations in the Rattle Poetry Prize, the Atlantic Monthly Student Writing Contest, the 2007 James Hearst Poetry Prize, the 2009 Indiana Review Poetry Prize, the 2013 Troubadour International Poetry Prize, and three Pushcart Prize nominations. He is the creator of the Transatlantic Poetry Reading Series and his most recent collection of poetry is The Silence Teacher (Poetry Salzburg, 2013)