THE AUTUMN CARNIVAL OF DEATH

One Autumn evening I was sitting at home, writing a story about love. Simply about love. About love and nothing but.

A young man meets a girl. Through the narrow alleys of some little seaside town, they reach the sea and plod along the beach…

Deserted. Dusky. Empty of people.

Because it’s already November. Winter. And summer’s not coming anytime soon.

In other words, crap.

But I liked it. Even though I didn’t know how to end the story. So I set the story aside and switched on the television. The host of some talk show was interviewing people who had experienced clinical death.

“We were at a birthday party,” a girl was saying, in a troubled voice. “Then we decided to have a swim…”

“This was a lake, right?” asked the host.

“Right, a lake. And, kidding around, they pushed me into the water. Suddenly I found myself in pitch darkness.” The girl fell silent. “And then I saw a bright, shining light… A woman came out of the light and said, ‘Hello. My name is Elizabeth.’ She took me by the hand and led me to Heaven.”

“Heaven? That’s what you think now?”

“No, that’s what I felt then, that it was Heaven. All around there was this bright light and out of this light there came this sensation of love, joy, contentment. I was simply surrounded by love, it was literally pulsating.”

“And who was this Elizabeth?” asked the host.

“My guardian angel… guardian angel…” the girl repeated, twice. “That’s what I think. Overall, dying is cool!”

“But you came back, didn’t you?”

“Yeah, I came back. Because Elizabeth said it wasn’t my time yet. And I said, ‘But I don’t know how to go back.’ And Elizabeth said, ‘See you…’ And I woke up in the hospital.”

A heavy-set Black woman got up from her chair.

“I don’t believe you can die and come back,” she said, talking very fast. “I think death is death! You don’t come back from it.”

I turned off the television and, sitting down at my desk, wrote an ending to my story.

The heroine turns out to have an extremely rare disease, as a result of which, once a year, most often in the Spring, she falls into a faint without warning. The fainting spell can come at the most inappropriate time and in the most inappropriate place. It so happens that the heroine visits a swimming pool. And as she’s climbing down the little ladder into the water, she has a fainting spell…

The story ended like this:

“There were many people in the swimming pool, but no one noticed how she drowned.”

After typing the last period, I decided to go out for the mail. There were two letters in the box. One was from the library. It said my books were already three years overdue. Out of the second envelope, a postcard fell.

On the postcard was a picture of a beautiful, old-fashioned mansion with tall columns, and a park stretched out all around it. A very nice postcard. The text was also very nice, written in an obviously feminine hand:

“You are invited to our Autumn Carnival.

D.”

And that was it.

No time, no place… Curious…

With this strange epistle in hand, I set off to visit my old friend, Mr. Schulz.

Mr. Schulz was drinking tea.

I handed him the postcard, “Have a look at this mysterious invitation. Perhaps you can guess the riddle? You have such a large store of life experience to draw upon.”

“Yes, I’ve got life experience, alright,” confirmed Mr. Schulz. “Well, let’s see… let’s see…”

Having turned the postcard over this way and that, he said:

“There’s no mystery. ‘D’ is Death. She’s inviting you to an Autumn carnival. You do like Autumn?”

“Sure. I like it.”

“Well, there you are. Those who like Autumn, as a rule, die in Autumn.”

I grew alarmed.

“But, Mr. Schulz…”

“Come, come, my boy… Now do you really think you’ll live forever?”

“Not forever, but…”

“Oh, do drop it, now,” he interrupted. “It would make some sense if we never died at all. But as things stand: a bit more, a bit less… What’s the difference?”

Mr. Schulz resumed sipping his tea.

“Easy for you to philosophize,” I retorted, in offense. “But what if…”

He interrupted again:

“Hey, you know what? Why don’t you take your camera with you and ask Death if you can take her picture. Then you can blind her with the flash, and take off!”

“God, what nonsense!” I exclaimed angrily and left Mr. Schulz.

I came back home and turned on the radio.

“In love, we have to come to each other’s aid,” sang some French songbird, “for only then can we withstand this world. Come to my aid…”

The street lamps came on outside. Passersby gradually diminished in number and disappeared.

Night fell.

An old, black automobile appeared on the street. It moved very slowly. Driving up to the entrance of my building the car stopped.

I immediately understood this was meant for me, and stepped out.

The car doors opened. I slipped inside. The car set off. Again it moved very, very slowly.

There was no one inside the car. Not even a driver. The steering wheel turned by itself. Out the windows, some unfamiliar little streets swam by.

I dozed off to the hum of the engine.

When I woke up, the car had stopped in front of a beautiful home with tall columns. The same one as on the postcard.

The doors, decorated with fancy carvings, opened to reveal a wide marble staircase. On a soft carpet covering the steps, I climbed up to a brightly illuminated hall. An orchestra sat on a balcony. The conductor’s white-gloved hands flew up — and there sounded a bewitching, unearthly melody.

I knew my classical music pretty well, but these eerie notes were completely alien to me.

Dancing couples began to whirl, rushing by in a vortex. And who wasn’t there: harlequins in red and white tights, gnomes in caps with bells, elves with delicate dragonfly wings, princesses in crinolines, knights, clowns, mermaids. The bright colorful costumes dazzled my eyes.

A girl, in a white lace dress and golden mask, covering the upper portion of her face, rushed up to me.

“Are you bored?” she asked, looking into my eyes inquisitively. “Are you feeling down at our merry celebration?”

“No, no, of course not!” I wanted to reassure my new acquaintance. “It’s just that, for me, all this is very unusual. This magic music, happy people, a beautiful hall… You have to understand that where I come from, there’s nothing like this. Well, there is, but…”

“Let’s not talk about anything sad,” the girl smiled. “Let’s dance. Listen, the melody’s coming to an end. In a moment there’ll be another.”

Her fingers rested on my shoulders. And we glided smoothly over the black-and-white checkerboard floor.

“Take your mask off,” I whispered in her ear. “Please…”

“I will, if you promise not to fall in love with me.”

“I promise.”

The girl fulfilled my request. And I saw her eyes…

I forgot my promise… I forgot myself…

I drowned in her eyes at once, like in a whirlpool — not bemoaning it one bit.

“Listen,” her voice reached me from afar. “What’s the matter with you? How are you feeling?”

“Like I’m in heaven,” I whispered.

“Well, then, we need to go. The time has come,” she pronounced the mystifying phrase. “Let’s go to the park. At this moment Autumn is there holding sway. And the air is redolent with the sweet scent of dying.”

The park paths were bestrewn with yellow leaves. We strolled, unhurriedly. Where to? Nowhere. Just strolled.

The trees parted into a clearing, and we emerged in front of a pond. Yellow leaves also covered the surface of the water, which rocked them gently.

We found several attractions around the pond: a house of mirrors, a shooting gallery, all sorts of carousels, a Ferris or “devil’s wheel”. Summer here was probably quite a cheery place. Music in the air…

But now it was late fall.

All the same, a little girl was standing on the semi-circular wooden platform, a stage. She wore a light blue dress, with a ribbon of identical blue fastened to her curls. On catching sight of us, the child curtsied and proposed:

“Would you like me to put on a concert for you?”

Without waiting for our consent, the youngster drew an imaginary curtain and started dancing to imaginary music, singing:

“La-la-la… La-la-la… La-la-la…”

When she finished, we started clapping. The child gave bows all around and, springing off the stage, ran over to us. She looked my companion over intently, all eyes.

“How are you, then, my sweet?” my new friend asked her. “Are you getting accustomed?”

“Yes, madam,” the little girl replied, shyly.

“You’re not missing home?”

“No, madam.”

“And you’re not afraid of death anymore?”

“Oh, madam!” the child cried out, and her face shone with joy. “Death is the most wonderful thing in the world.”

A cold shiver ran up my back. All of sudden I didn’t feel quite so snug in this autumnal park.

“Oh, Uncle Valery!” the little girl exclaimed, having noticed me. “Hi.”

In that moment I recognized her, too. This was the daughter of a cousin of mine. Olga.

She’d died two years before, of a blood infection.

“Hello, Olga,” I muttered.

“How’s my Mommy? Do you ever visit?”

I took my companion by the elbow.

“For God’s sake, let’s go.”

I led her away in the direction of the “devil’s wheel.”

“See you, Uncle Valery!” Olga called after us.

This “See you” sent another shiver down my spine.

Next to the “devil’s wheel” sat a decrepit old man. As we approached he got up with difficulty and, seeing the girl, mumbled through a toothless maw:

“Hello, madam.”

“Hello, my sweet,” the girl replied. “So how’s everything here? You’re not missing home?”

“No, mistress, I don’t miss it. It’s so nice to die.”

The girl indicated one of the wheel’s little cabins nearby.

“Would you give us a ride?”

“For many, many years now nobody’s ridden on the wheel,” said the old man.

“We will,” the girl shook her head insistently.

The old man crept into a ramshackle booth. Something inside there began loudly droning, and the “devil’s wheel” slowly started to move.

I seated the girl in the cabin, climbed in myself, and we set off on our journey upwards, above the autumnal park.

“You’re not afraid of heights?” she asked.

“Terribly afraid,” I answered frankly. “And you?”

“Me too.”

“Then let’s hold hands and close our eyes,” I suggested. “That way it won’t be so scary.”

“Let’s!”

We held hands and closed our eyes. Pretending I didn’t really mean to, I put my arms around her shoulders. She, also pretending she didn’t mean to, pressed herself to me, eyes shut. And smiled. I looked down, expecting to see the park, the pond, the house with the columns.

THEY WERE ALL GONE WITHOUT A TRACE!

Stretching out to the very horizon was a smooth, watery surface. The “devil’s wheel,” slowly spinning, had its bottom half underwater. Our cabin, having already crossed the highest point, was now descending. The empty cabins below us were vanishing into the murky depths, one after another. A few more and we’d be swallowed up too. And then, a little later — after all, the wheel wasn’t stopping, it kept on spinning — our drowned corpses, having made the fatal half-circle, would surface on the other side, and everything would repeat itself again and again and again…

Thus, day after day, the “devil’s wheel” would spin; a school of voracious fish would anxiously look forward to its regular banquet. And very soon only a couple of skeletons, picked clean, would ride apathetically on this wheel of death that protruded desolately out of a boundless ocean.

I could see this all so clearly that trembling uncontrollably I shut my eyes again.

“That’s it,” echoed a resounding voice. “Hey, what’re you, sleeping?”

I opened my eyes.

What the hell? The autumnal park was back. The old man sat by the booth. And the girl was already standing in the path, her hands stretched up to the sky.

Snowflakes twirled through the air.

“Look! Look!” the girl cried. “It’s the first snow! It’s falling on the yellow leaves. How beautiful!” And she started making circles along with the snowflakes, as if she were one of them.

Running over to me, the girl playfully pinched my nose.

“What’s the matter, you mean you really fell asleep?”

Instead of an answer, I gave her a kiss. I’m not sure myself how it happened. I just kissed her.

She didn’t return my kiss. But she smiled. Sadly.

“Why’s your smile so sad?” I asked.

“Guess.”

I retreated half a step.

“You mean you’re… You’re name is…”

“Diana,” she covered my mouth with her little palm. “Call me Diana. Or Denise. Whichever you prefer.”

Recalling Mr. Schulz’s advice, I laughed bitterly.

“Diana,” I said, “or Denise, would you like me to take your picture?”

“Oh, no, don’t,” she wrinkled up her nose adorably. “I look terrible.”

“You look beautiful.” I got my camera. “Smile. Here comes the little birdie.”

She smiled. But the little birdie didn’t come.

We strolled along the park paths, first one, then another… The fallen leaves rustled beneath our feet. Snowflakes fell on our heads and shoulders.

Before long we walked over to the park exit — a small iron gate in a fence. On the other side of the fence stood the black car.

“Time for you to go,” Denise (or Diana) said, simply.

“You’re… letting me go?”

I just couldn’t believe it! I couldn’t!

She tousled my hair.

“You know, there’s a story by Bunin, ‘Cold Autumn.’ In it the hero tells his beloved, just before his death: ‘You live on a while, enjoy your time on earth, then come to me.’ That’s what I’m telling you: ‘Live on a bit longer, enjoy yourself; you don’t need to come to me, I myself will come to you.”

We were silent a while. The snow fell, soundlessly.

“Can I kiss you again, one more time?” I asked. “A goodbye kiss.”

She nodded.

Afterwards I got in the car. It drove off. This time in a hurry. But all the same I managed a long look at the delicate, small figure in white, slowly receding into the depths of the park.

The next day I stopped by Mr. Schulz’s. He was still drinking his tea.

“So, Valery, did you end up going to that carnival at Death’s place?”

“Yes, Mr. Schulz, I did.”

“And made it back?”

“As you can see.”

“Ma-a-arvelous… But how’d she see fit to let you leave?”

“Very simple. We got to liking each other.”

“All the more reason for her not to let you go.” He gulped some tea. “So, what did she… you know, look like?”

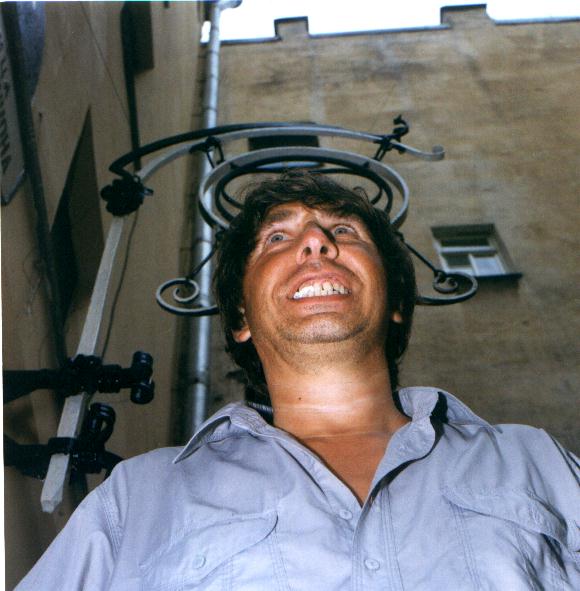

I showed him the photo.

“That’s her.”

“Not a bad-looking girl,” said Mr. Schulz.

Back home I stuck the picture in a frame and hung it over my desk. And now, whenever I’m writing my stories out long-hand, and then typing them up on my computer, I glance up from time to time at that cherished snapshot — from which, smiling wanly, SHE looks back at me.

BELOVED, WHEN YOU COME FOR ME I WILL MEET YOU WITH OPEN ARMS.

____________________________________________________________________

VALERY RONSHIN (1962) graduated with a degree in history from Petrozavodsk University in Karelia and went on to study at the Literature Institute in Moscow. He now lives in St Petersburg. He started writing relatively late but broke into top literary magazines almost immediately. Ronshin says that for the first thirty years he was “just living a life”, moving from one provincial town to another and traveling on foot in Central Russia. He worked at different menial jobs and taught history for a spell before becoming a professional writer. As such, his greatest debt is to Daniil Kharms, the acknowledged Russian master of the absurd. Like Kharms, Ronshin is also a successful children’s author with more than 20 books to his name. Unlike Kharms, he wrote the first detective novel for Russian young adults. Ronshin, whose children’s stories appeal to grown-ups as well, considers that “a writer’s job is to describe his age and die.”

____________________________________________________________________

About the Translator:

JOSÉ ALANIZ, associate professor in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures and the Department of Comparative Literature (adjunct) at the University of Washington – Seattle, received his Ph.D. in Comparative Literature from the University of California at Berkeley. He published his first book, Komiks: Comic Art in Russia (University Press of Mississippi) in 2010. One of his current writing projects deals with history in Czech comics.

____________________________________________________________________

Read more work by Valery Ronshin:

“My Flight to Malaysia” a short story in B O D Y