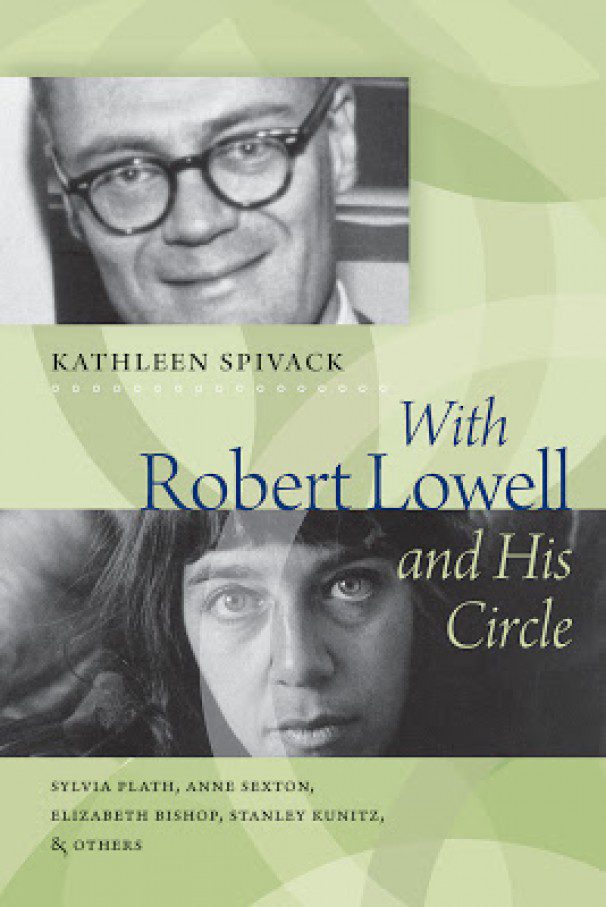

With Robert Lowell And His Circle

By Kathleen Spivack

Northeastern University Press

256 pages

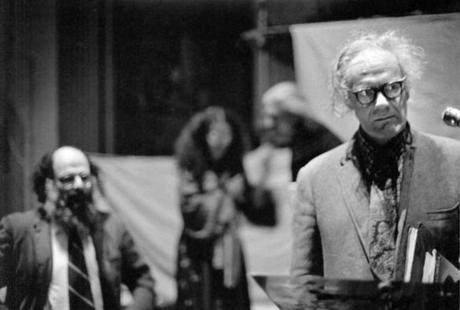

Examined through the lense of literary nostalgia, Boston, Massachusetts in the late 1950s and early 1960s seems an almost absurdly inspiring place, when poets like Robert Lowell, Anne Sexton, Stanley Kunitz, Sylvia Plath, Ted Hughes, Frank Bidart, Robert Pinsky, Maxine Kumin, and many others presided over the city’s literary life, complete with gray flannel suits, knit ties, and three martini lunches. At least that’s how memoirs, including Kathleen Spivack’s With Robert Lowell and his Circle, have portrayed the era.

An undergraduate student in the late 1950s, Spivack won a fellowship to study with Robert Lowell at Boston University in 1959. Leaving Oberlin in her senior year, she joined the cadre of poets who orbited around Lowell in one of the most remarkable eras American poetry has known.

Maudlin gin nostalgia aside — and it is difficult to put this aside, especially as American culture is currently engaged in a public reexamination of these years, via Mad Men and other popular media — it must have been a unique experience to study with Lowell, then at the height of his powers and reputation, and also struggling deeply with manic depression, before new medications would make his episodes less frequent in the late ’60s. It’s also important to remember that this was before the institutionalization of creative writing programs, so Lowell was basically making it up as he went. Spivack, in her elegant prose, captures well the mixed feelings of awe and terror she felt in class. The following takes place during a discussion of a classmate’s poem.

We’re all afraid. If he is entering another breakdown period, he might turn and lash out at anyone who accidentally irritates him. Who knows what is going on in that tortured New England mind? Lowell frowns with effort. Another long, unsatisfying silence. There is the almost inaudible sound of Lowell’s nasal breathing. He is thinking. Everyone tries to refrain from saying something stupid. The room gets darker. Sylvia does not move, watching.

That classmate, of course, is Sylvia Plath.

But Spivack’s memoir is about more than just telling tales out of school. For a girl in her early 20s, she seems to have had a remarkable range of experiences as an outsider in Boston. Working a variety of jobs to make ends meet, struggling through cold Boston winters in rickety rooming houses, drinking endless cups of coffee at Howard Johnsons, roaming Harvard Square: Spivack seems to have done it all in Boston, and she gracefully captures the essense of the era.

From the late ’50s to the late ’70s, I was able to observe the culture and its impact on both Robert Lowell and Elizabeth Bishop. I worked at Boston City and State Hospitals, the Whitty Boiler Manufacturing Company, the State House, at Harvard, and the posh Atlantic Monthly, peering through the large windows onto the Public Gardens. On the surface Brahmin Bostonians were classically well educated, extremely formal, and well mannered. This society was elitist, literary to the max. But underneath lay a world seething with contradictions, repression, and rebellion.

It wasn’t only poets who were attracted to Lowell, of course. The now-eminent poetry critic Helen Vendler was also one of Lowell’s students in these years, and her appearence in the book exemplifies what will be the main attraction for readers: Seeing the private personalities of now-famous writers and scholars, before they became public personas.

[Helen Vendler’s] eyes sparkled. She spoke with conviction, scholarship. She had a scintillating mind. Everyone came awake when Helen spoke. There was electricity between Lowell and Vendler as they came at a poem from different sides.

Perhaps memoir is always elegiac. Spivack’s account is doubly so: By the time Lowell died, they had become close friends — though never lovers, as Spivack goes to pains to point out. She had a similarly close relationship with Elizabeth Bishop, who seems to have relied on Spivack for support after her relocation to Boston. And of course Plath and Sexton met their tragic, melodramatic ends shortly after their studies with Lowell.

But this book is also an elegy for a bygone age, of Boston, of poetry, and of America. Too many changes have taken place since the 1950s, not all of them bad, for it to be conceivable that another group of poets could come together around a central authority quite like this. What Stanley Kunitz called “the democratization of genius” has affected our literature, our universities, and our daily lives.

When I first came to Boston on a reckless adventure, I didn’t expect it to become the cornerstone of a constructed life. I didn’t know or understand Robert Lowell’s poetry. Nor did I realize that, sitting in Lowell’s classes among these poets, I would become a survivor, a witness to their journeys. But after Lowell’s death I realized this was meant to be, had to be.

Spivack is at times repetitive, revisiting and repeating episodes, phrases and conclusions, yet this is a revealing and touchingly personal memoir that presents a more vividly emotional picture of this era of poetry in Boston than has been done before. Peter Davison’s The Fading Smile is another masterful memoir of this time in Boston, but where Davison is nearly purely literary, Spivack is nearly purely personal. Her passionate candor enlivens these pages.

–Stephan Delbos