Tabula Rasa

Eight years ago, on August 26, 2015, after taking my two children to school, I sat down in my book-lined study to read the BBC Online — part of my morning routine as stay-at-home dad, my euphemism for unemployed father. I scrolled to the science section and noticed an article, “Aphantasia: A life without mental images.” The title struck me as odd because I’d always interpreted “mental image” as a metaphor.

I’ve privileged the life of the mind over that of the body. As a child, I’d rather read the World Book Encyclopedia than ride my bike or eat dinner. My mind was the one thing I thought I could trust.

On a rainy night in January, 2004, I was driving my mother to the airport in Harrisburg — she had come out to help take care of my year-and-a-half-old daughter while my wife and I worked on repairing the marriage that I had nearly destroyed—and out of nowhere, she asked, “Did Larry ever do anything to you?” Without pausing to think, I answered “Yes” and then added, “but I was never alone with him.” Truth and impossibility existed simultaneously. She mentioned that he always took me up early to Royal Ranger campouts before the other boys arrived and kept me for an hour or two after everyone else had left. I couldn’t remember anything.

I used to watch police procedural shows, especially CSI and Law and Order: Criminal Intent. Science against the criminals. But whenever the sketch artist arrived to help a witness create a picture of the perpetrator, I felt anxious. Witnesses who had only seen someone for an instant could remember countless details about total strangers. If my wife ever disappeared, I couldn’t describe what she looked like beyond “She has black hair and a dimple in her chin.” Period. Once we had kids, it was even worse — I constantly feared some man would abduct them. I was a poor parent since I couldn’t describe my own children, but I simply could not generate images of them, so I kept current pictures of them with me.

Some researchers and commentators describe aphantasia as “the Mind’s Eye Is Blind.” They add this is not a disability, like physical blindness, but is more like being left-handed. My brother’s left-handed, and I remember my parents forcing him to use his right hand to hold his fork at the dinner table.

In a grad school survey of literary theory, I was introduced to Descartes’ idea of the tabula rasa. I have since learned that the phrase goes back to Greek and Islamic scholars, but we only encountered it with him. The mind begins as a blank slate, and through learning and experience, knowledge and identity are inscribed on it. It complemented the one other thing I knew about Descartes, cogito ergo sum. What happens when what I think does not reflect who I am?

One early idea was that aphantasia was linked to trauma. That resonated with me. Did my mind simply stop visualizing because it didn’t want to see what I had been through? That was my assumption. Only when I started researching it again to write this essay did I discover that it has a genetic component. I asked my son, and he already knew that he had it. I asked my daughter a few weeks later when she came home from Colgate—she has it too, but did not realize it.

Because both my children are aphantasic, one of my parents must be as well. That’s the great thing about genetics. For Christmas my parents visited, and while my kids and they were playing Rummikub, I asked them to close their eyes and think of each other, and tell me if they could see their spouse in their mind. My father said yes, but the question made no sense to my mother. At 76, she discovered that 98% of the rest of the world had an interior reality much different than hers. She wants to ask her six siblings if they share the same trait.

I have never had a particularly good imagination. Really, it’s kind of dire. It irritates my wife that I can’t imagine a future. I’m not sure how much of that is aphantasia and how much of that is growing up with an imminent Rapture, where each reference to the next church service ended with the qualification, “should Jesus tarry.” The prophecies indicated the world would end by the mid-1980s.

For over a decade during therapy, Rhonda would tell me to close my eyes and visualize my sexual trauma and then put it in a box. I followed along with the exercise, narrating as I put it in a box in the back of the top shelf of a closet in my mind. We did a lot of visualization work, none of which seemed to help. When I eventually discovered the problem and explained it her, she was utterly surprised that such a condition existed. She didn’t have a Plan B.

I do dream though, but not vividly. Each morning, I try to remember the dreams of the previous night, but at best I get a flickering moment or two, and they evaporate by the time I’m out of bed. I remember only one dream, ever, from when I was in Junior High: a girl unzipped her pants and put her penis in my mouth and then peed. That dream, it turned out, was not a dream, but my brain reframing reality. Maybe a mind without images provides an evolutionary advantage.

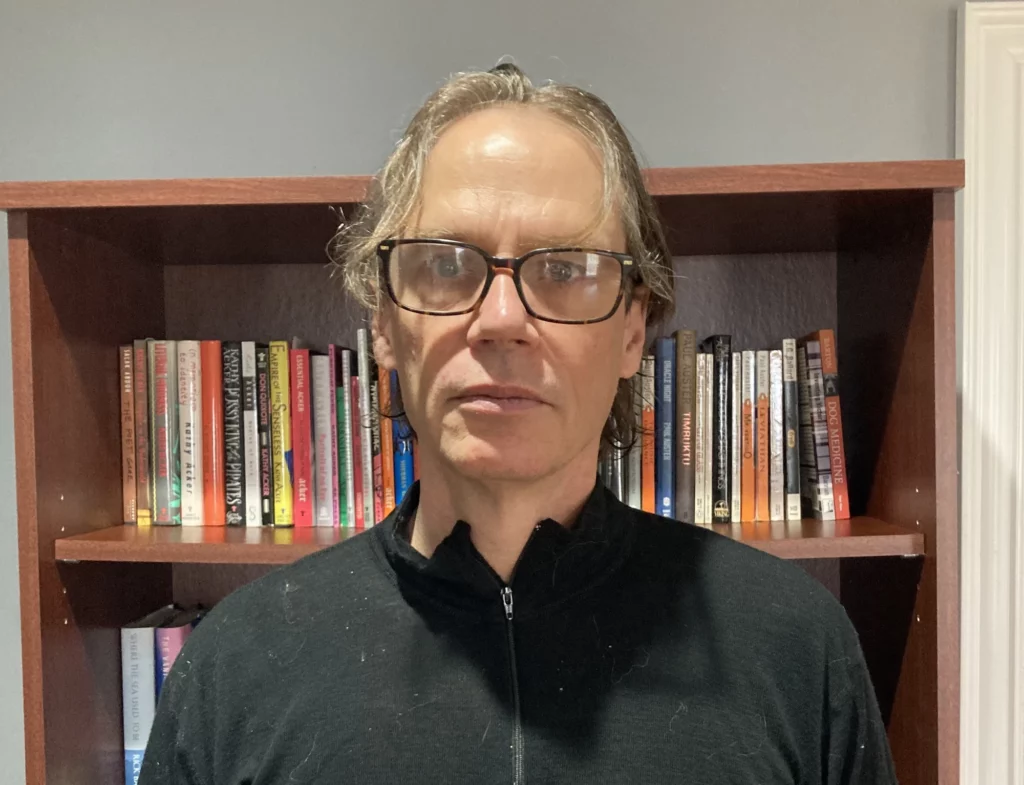

MICHAEL HARDIN lives with his wife, two children, and two Pekingese in rural Pennsylvania. Originally from Los Angeles, he is the author of a poetry chapbook, Born Again (Moonstone Press, 2019), has had poems and flash CNF published in Seneca Review, Wisconsin Review, North American Review, Quarterly West, Moon City Review, among others, and has been nominated for a Pushcart.