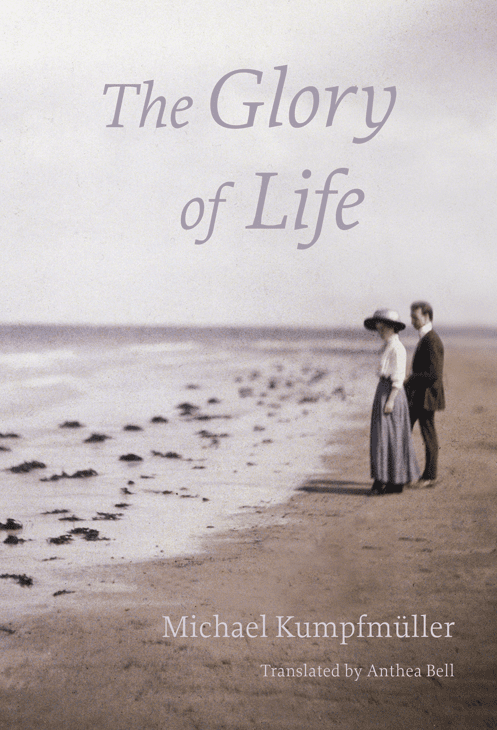

THE GLORY OF LIFE

(an excerpt)

The Glory of Life

A novel by Michael Kumpfmüller

Translated from the German by Anthea Bell

Published by Haus Publishing

It is the first story in which he has almost believed for a long time, the first that he knows he will finish, and in fact he has as good as reached the end. It is not too long, only a few pages, but he seems able to write it, has even thought of reading it aloud, which has always been a good sign with him. He is working, he feels strong, he has actually been able to write to M. at last, something about a letter from her that was burnt and one from him, and what has happened since July. He immediately falls into his old tone of voice, with the unfortunate result that he does not express himself very precisely. Something great has happened to him, he begins the letter, he mentions the Colony, his originally vague idea of going to Berlin instead of Palestine, how difficult it has always been for him to live anywhere alone, but for that difficulty, too, he found help in Müritz, help that was improbable in its own way. So now he is here in Berlin, has been in Berlin since September, obviously not alone, although it may sound so. He is living in a villa with a garden, almost in the country; the apartment is the best he has ever had. The food is such and such, he writes, his state of health … ah, well … and then, at the end, he makes a quick obeisance to the ghosts in the air, he even mentions the word fear in quite a prominent place, there is no other way to put it, for he ends the letter with the word fear, as if slamming a door behind him for ever. It has taken him two evenings to write. He is glad that M. does not know about his new life, that she is living in Vienna: she seems to have been in Italy for a little while, far from Steglitz, as good as out of reach.

Several more parcels and little packets have arrived recently, neatly numbered so that it will be obvious if one of them has gone astray, which unfortunately does happen. His mother has sent a bottle of red wine, a pair of slippers, four plates, a huge bottle of home-made raspberry juice, and also butter, as usual, even a loaf of wholemeal bread, although by now he prefers the bread they eat in Berlin. Ottla is coming tomorrow. He has sent her a list of things that they urgently need: three kitchen towels would be useful, two tablecloths, the foot-muff already mentioned several times; he hopes very much for that because, he is sorry to say, he has cold feet all the time.

In contrast to Max’s visit, he does not doubt for a second that Ottla’s will be a success, and sure enough Dora and Ottla get on well at once, even if it is only for a few hours, for unfortunately his sister must go back again that evening. If Ottla has had any doubts about his life in Berlin, they are dispelled at once. She has nothing but praise for the apartment, its almost rural surroundings, and even her brother’s state of health seems to be giving no cause for concern at the moment. Anyone can see, she says, that however diffcult life is outside, you two are doing well here. There is much rejoicing about the things she has brought, which even include a spirit stove that delights Dora above all, and then Ottla helps her in the kitchen, where he hears them talking like old friends for a long time.

On the way to the station later that afternoon, Ottla says she can easily understand him. She isn’t like us, but that’s just what attracts you to her, isn’t it? To mention the most obvious difference, Dora is from the east; but all the same there are similarities between them, he thinks, for instance the common sense that distinguishes both young women, the way they laugh. His father would see only the east in her. Today is probably the first time that he and Ottla haven’t talked about their father. Not a word about him for all four hours, now that they are both leading their own lives in their own way, Ottla with Josef and the girls, Franz here with Dora in their Steglitz apartment.

To his surprise, he goes on writing without any break. Even the night after Ottla’s departure he begins a new story. He is not sure where it will lead him, but at any rate it will not be to Berlin, because the story is set in an animal’s underground burrow. He has not slept really well for days, but he is writing – he is sharing an apartment with this young woman, but all the same he is writing. He has already read the Frau Hermann story aloud to Dora, who laughed several times, although there isn’t really any story about Frau Hermann that she doesn’t know already.

He is no longer looking only inside himself, in all seriousness he has the impression that, as if at a slight turn of the head, everything has changed, astonishing as that is. As if he had never had to do anything but turn his head and all of a sudden he would be looking outwards, to where Dora is, and the companionable experience that he connects with her.

He has written about animals quite often before, about the humblest of creatures, a cockroach, an ape, a giant mole, a vulture. He has written about dogs and jackals, he has written marginally about leopards and the cat that eats the mouse.

The beginning of the new story runs like this: I have built the burrow, and it seems to be successful. From the outside all anyone can really see is a large hole, but in fact this hole leads nowhere. After only a few steps, you come up against solid natural rock.

What else? The first snow has fallen, it is very cold, with hardly any sunlight although the sun does break through now and then. In such weather he hardly leaves the house for days.

The people of Berlin are starving, donations of food are arriving from all over Europe: that is something that he does not follow closely, but now and then he hears some detail from Dora, when she goes shopping or meets her friends. They are getting used to the sight of beggars in the streets; sad to say, by now half the city is full of beggars, the citizens are worn out, and desperate in a forbearing kind of way. The situation is worst in the Scheunen district, although there has been no repetition of the pogrom-like acts of violence in November. Dora says that the Jewish People’s Home is in terrible trouble; she would like to do something – not just make soup for the poorest of the poor, but do something to change matters.

Ought one to write about the world or change it?

He has answered Robert’s last letter, explaining why he says almost nothing about himself, or rather he does not so much explain as state the fact that nothing much is happening. He does not write to his family, to Max, or to his other half-forgotten friends, but his conscience there is clear; the more so because he seems to sense that he does not have much time left.

He is under pressure, and doesn’t know how well he will manage to stand up to it; meanwhile he ostensibly has more time on his hands than ever before. Perhaps this is happiness, he thinks, this form of extravagance, evenings spent in the dimly lit room when they read aloud to each other, Dora in Hebrew from the Torah, or he reads something from the Grimms, or from Hebel’s stories, from the Treasure Chest of a Family Friend From the Rhine. He particularly likes Hebel’s story of the miner. At such moments he feels as if he has all the time in the world, that he is not wasting time, because he knows that after a few minutes he will go to his desk, and then stay sitting there after all, complicated as these states of uncertainty are to him: moments when she leans against him or crosses her legs, a mixture of expectation and fear.

He roots around in his burrow for a few days and nights, surprised to find how simple it all is.

When he gets dressed in the morning, shirt and tie, standing in front of the mirror in the little bathroom, when he washes and shaves and then dresses, putting on his dark suit, always dressed to the nines, it is as if he had an appointment to meet her for breakfast in a café and would soon be seeing her there, but all the time she has been here in a dress or a blouse that he knows.

He wonders when he picked up that habit. Or can you rely on things to be right just when they need to be?

His evenings, too, are extraordinary, for at some point you must take your clothes off and prepare for the night. They share the room, he is not alone, but that does not disturb him, far from it. This, he has always thought, is exactly the way he should live some day.

____________________________________________________________________

MICHAEL KUMPFMÜLLER was born in Munich, Germany, in 1961 and now lives in Berlin. His debut novel The Adventures of a Bed Salesman was published in 2003 to critical acclaim, and his 2009 novel Message to All won the Alfred Doblin Prize.

____________________________________________________________________

About the Translator:

ANTHEA BELL’s translations include W.G. Sebald’s Austerlitz, Wladyslaw Szpilman’s memoir The Pianist, E. T. A. Hoffmann’s The Life and Opinions of the Tomcat Murr, as well as a large selection of Stefan Zweig’s novellas and stories. Her prizes and awards include the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize with the author, the Helen and Kurt Wolff Prize, the Oxford-Weidenfeld Translation Prize, and the Schlegel-Tieck Prize.