By Andrew Field

In two letters written to the visual artist Loren MacIver, dating from 1949 and 1953, respectively, Elizabeth Bishop sums up, through her unique descriptive acumen, two crucial features of MacIver’s paintings. In doing so, Bishop sets down a template through which one may think about and understand both her poetry and MacIver’s paintings. In the 1949 letter, Bishop writes, “Your show [of paintings] was so lovely & do tell me if you sell any more. If I were rich, I’d buy the crocus one, I think – oh, several. The first impression is one of such beautiful colored atmosphere – air, breeze, mist, etc.” Four years later, in March 1953, Bishop writes of MacIver’s “out-of-focus dream-detail,” her “divine myopia” and “marvelous myopia.”

The two features that Bishop focuses in on are the blurred lyrical atmosphere of the paintings – their barely tangible, ethereally enveloping qualities (“air, breeze, mist”) – and the close-knit “dream-detail” as presented by MacIver’s “divine myopia.” (In “Sandpiper,” Bishop would write, “The world is a mist. And then the world is / minute and vast and clear.”) It is as though Bishop, in her letters and her poems, is practicing putting into words what she sees enacted in MacIver’s paintings – a kind of “marvelous myopia,” in which there is a constant dance between zeroing in and zooming out, sand and mist, nearness and distance, the gestalt and the detail, “the panorama and minutia.”

Indeed, “Bishop’s vision multiplies or shifts perspectives, aware of life at the peripheries of our interpretations.” Or, as Lorrie Goldensohn writes, “Bird in relation to flight, prophet in relation to believer, flesh in relation to spirit, poet in relation to poem – the potential readings in the poems are many and various, but very nearly all are pegged on questions of space and position.”

Bishop and MacIver share these concerns with the ways in which perspective and perception shape one another. It seems strange, therefore, that there has been very little written about their relationship and the relationship between their work. Goldensohn is right to say that Bishop’s “firm connection to the visual arts engages more than a single question of influence,” but it still seems important to extend that circle of influence – normally constituted by Max Ernst, Georgio De Chirico, Paul Klee, Kurt Schwitters, Alexander Calder, and Joseph Cornell – to include MacIver as well. Even in a book as ostensibly devoted to Bishop and the visual arts as Peggy Samuels’s Deep Skin: Elizabeth Bishop and Visual Art, MacIver’s influence is relegated to a footnote, an excerpt of which reads: “I have found little evidence that MacIver served as a significant mediator for Bishop’s understanding of visual art. Although MacIver had considerable success as a painter…she was not particularly articulate about her work.”

Samuels’s claims – that MacIver did not serve “as a significant mediator for Bishop’s understanding of visual art,” and that MacIver “was not particularly articulate about her work” – are questionable. Besides Bishop exchanging numerous letters with MacIver and her husband, the poet Lloyd Frankenberg, over the course of 35 years of friendship, Bishop lived in September and October of 1938 with MacIver and Frankenberg in their cabin in Provincetown, Massachusetts. Bishop and MacIver even planned on coming out with a book together in 1939. Bishop also stayed in MacIver and Frankenberg’s apartment in New York in 1967 and 1968. This would suggest not only a friendship based on shared affinities, but also that Bishop had plenty of opportunities to see MacIver’s work in the intimate setting of MacIver and Frankenberg’s home(s).

Samuels also asserts that MacIver “was not particularly articulate about her work,” although she does not cite any evidence to support this claim. It is true that MacIver published very little about her own work. But this does not mean that she “was not particularly articulate about her work.” One might even suggest the inverse: that she was articulate about her work, but filtered her thoughts and feelings through a lens both modest and reticent. Indeed, the more one thinks about Bishop and MacIver, the more there seem to be very vital connections. Both went against the grain – Bishop against the trend of Confessional poetry, MacIver against the trend of Abstract Expressionism – in order to find their own idiosyncratic voices. And both often incorporate into their works a certain lyricism combined with a kind of angular irony. It is for these reasons that MacIver and Bishop influenced each other in significant ways.

“SHACK”

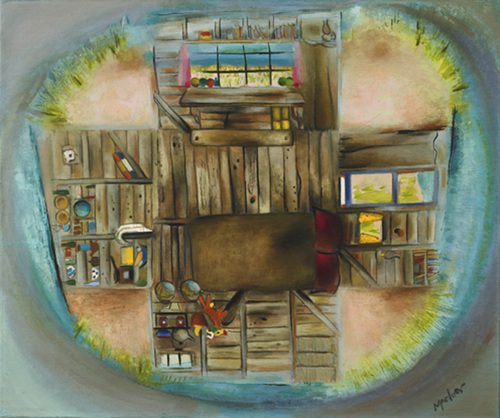

Here are two examples to illustrate this influence – the relationship between MacIver’s “Shack” (1934) and Bishop’s “The Monument” (completed in 1938-1939). “The Monument” is characteristically and convincingly considered to be heavily influenced by Max Ernst’s Histoire Naturelle, especially in the context of “the technique of frontage,” and in lieu of Bishop’s own notebook entries. Yet the influence of MacIver was just under Bishop’s nose. Here is MacIver’s “Shack”:

The painting is hypnotic and mystifying. It isn’t clear initially exactly what one is seeing, even though the title helpfully adumbrates the ostensible subject matter. Is this a bird’s eye view of a structure lived in by MacIver and Frankenberg? If so, how does one explain the way what would seem to be rooms are more like windows, shelves, floors and ceilings, holding improbably balanced books, a mug of steaming coffee, perhaps marbles or fruit, a bird, candles (or what seem like the end of a large toothbrush), and showing what appear to be seascapes and landscapes? It’s as if a kind of gravity has been relinquished in the picture, and one is peering through the peepholes of memory.

Yet this only tells half of the story. Turning to Frankenberg’s memoir Yellow Season, excerpts of which are published in the catalogue Loren MacIver: The First Matisse Years, one reads that “‘Shack’ was the interior of a room, with the four walls folded back so that you could see inside and out at the same time. Outside was a landscape-seascape. When you turned the picture four ways… you saw a different patch of landscape through each window, porthole or door, with different objects on or under the walls.”

What prompted MacIver to paint, not only the interior of a room, but with the “four walls folded back so that you could see inside and out at the same time”? It is as though the shack itself were (with perhaps more delicacy) Eliot’s “patient etherized upon a table,” bared and open to the elements. Perhaps this was MacIver’s way of representing as much of the shack as she could, without kowtowing overly much to representational strictures on or of perspective. For to allow the viewer to be inside and outside at the same time is to grant upon that viewer a perspectival freedom, a disciplined looseness within which one may absorb and roam around the qualities of the structure. It is the dance, as mentioned above, between points of reference – nearness and distance, say, or inner and outer. Even at the center of the painting is a kind of dance between boundaries that define and boundaries that confine: at the center is a brown-wooden cross, appearing like an abstract person, around which is traced an ill-formed circle. Beyond the circle is another confining and defining boundary – the frame itself. These delimiting boundaries contribute to the feeling that the shack is not on an island so much as it is an island, beyond the limits of which are traced the sky- or water-like concentric circles of blues, browns, grays and purples.

If impressionistically the painting breathes an insular openness, this estimation of self-containedness is not too far off historically. Three years before MacIver painted “Shack,” she and Frankenberg lived together in a self-proclaimed “shack” in the winter of 1932. As John I.H. Baur writes, “since neither poets nor painters [were] likely to be affluent in youth, there must have been difficult times, of which neither speaks.

Their home on the Cape, at North Truro, was a shack which they built entirely of driftwood collected on the beach. When nearby supplies ran out they gathered more at distant points, formed it into rafts and, picking an auspicious wind and tide, floated these down to their site. On the ocean side of the Cape it was not easy. With MacIver harnessed to the raft by a tow rope and Lloyd Frankenberg precariously poling to keep it off shore, they managed to amass enough supplies for a reasonably weathertight cabin. Heated by a wood stove, this was their only home during the winter of 1932. There was then no road near them and food had to be brought in by knapsack over a trail through the scrub pine. They did not try to winter there again but the shack remained their summer home until about 1940 when the war temporarily prevented its use.

Assuming the shack described in the above paragraph is the structure painted by MacIver, it makes sense that the painting would exude a singular kind of intimate warmth, through the light through the windows and the loving attention to detail, even as it also evokes a hardness and hardship, through the texture of the wood and the form of the cross. The painting, in its ramshackle, odds-and-ends quality, also makes an argument for the piecemeal method by which it was constructed. It seems a whole world unto itself, lonely but intricate. And like a good many of Bishop’s poems, it is unpopulated.

”THE MONUMENT”

Indeed, from another observer’s perspective, MacIver and Frankenberg’s domicile might have seemed too slight, too dangerous, and not worthy of being painted; (fortunately MacIver did not see it that way). But I wonder if this very feature of “Shack” – how something so seemingly un-monumental might be turned into a monument in MacIver’s painting – might have influenced Bishop’s “The Monument.” If it did, though, how else did it? To answer this, one needs to turn to the poem “The Monument,” from Bishop’s first collection, North and South. The poem begins:

Now can you see the monument? It is of wood

built somewhat like a box. No. Built

like several boxes in descending sizes

one above the other.

Each is turned half-way round so that

its corners point toward the sides

of the one below and the angles alternate.

Then on the topmost cube is set

a sort of fleur-de-lys of weathered wood,

long petals of board, pierced with odd holes,

four-sided, stiff, ecclesiastical.

The poem, beginning en media res with the excited, perhaps exasperated or even exhausted question, “Now can you see the monument?” suggests that before the poem begins, the writer and reader are looking at something from afar, yet the reader cannot see it. Suddenly the poem starts; and equally as suddenly the reader is presented with a structure that, like MacIver’s “Shack,” is enchanting but mystifying. The process of looking, seeing or noticing MacIver’s painting mirrors the process of the unfolding “Monument.” In both acts of perception, the perceiver begins off-balance, unsure of where exactly he or she is. Is what is seen a bird’s eye view of the “Shack?” If not, then what is being seen? Where in space is the reader situated in “The Monument,” by which he or she views this structure? It is only through the temporal process of perceiving these structures that the perceiver gains his or her bearings and foothold and can get a better sense of what it is, exactly, that is being read or viewed.

Bishop, like MacIver, is interested in the process by which things take shape in the imagination. Five years before her final drafting of “The Monument,” she wrote to her friend Donald E. Stanford, quoting from an article that “Their purpose (the writers of Baroque prose) was to portray, not a thought, but a mind thinking”. Bishop was passionately attracted to this idea of “a mind thinking” – all the fits, starts, jumps and qualifications that happen when a mind begins to cogitate and imagine. We can see this playing itself out in “The Monument” – the poem affects a revision in its unfolding, and what had been said in the first two sentences is contradicted by a “No” that sets the imagination down a different path. The process seems an almost painterly one, whereby the poet-painter sets down a line or daub on canvas, only to find it doesn’t fit into her developing conception of the work, and so she “crosses out” the line or daub – she smudges it or replaces it with something else. The poem-painting becomes a record of these transactions, a transparent or opaque palimpsest.

Had Bishop seen “Shack” – and there is no reason to believe she hadn’t, as “Bishop did go to see MacIver’s exhibits,” in addition to staying in her and Frankenberg’s homes – one senses she did not pick up structural details from this painting, however, so much as an overall tone-impression or feeling-tone. This seems in keeping with her temperament, which combined exactingness with a remarkable impressionistic flair. She wrote to Stanford in March of 1934:

Have you ever noticed that you can often learn more about other people – more about how they feel, how it would feel to be them – by hearing them cough or make one of the innumerable inner noises, than by watching them for hours? Sometimes if another person hiccups, particularly if you haven’t been paying much attention to him, why you get a sudden sensation as if you were inside him – you know how he feels in the little aspects he never mentions, aspects which are, really, indescribable to another person and must be realized by that kind of intuition. Do you know what I am driving at? Well, if you can follow those rather hazy sentences – that’s what I quite often want to get into poetry.

Bishop’s emphases on “hazy” sensation and intuition in this passage suggests that sometimes our most fleeting impressions of a person or a painting – that “first impression” that Bishop mentions in her letter to MacIver – come closer to a truth of that person or painting than some prolonged and arduous study. It follows that Bishop’s imagination of her monument is infused with the strangely redolent religious qualities of “Shack” – the shape of the wooden cross, the hardness of the wood – which Bishop transforms in her poem into the more satirical “a sort of fleur-de-lys of weather wood, / long petals of board, pierced with odd holes, / four-sided, stiff, ecclesiastical.” At the same time, MacIver’s choice of subject matter echoes Bishop’s description of her monument:

– The strong sunlight, the wind from the sea,

all the conditions of its existence,

may have flaked off the paint, if ever it was painted,

and made it homelier than it was.

Later in the poem, Bishop writes,

It is an artifact

of wood. Wood holds together better

than sea or cloud or sand could by itself,

much better than real sea or sand or cloud.

It chose that way to grow and not to move.

The monument’s an object, yet those decorations,

carelessly nailed, looking like nothing at all,

give it away as having life, and wishing;

wanting to be a monument, to cherish something.

The crudest scroll-work says “commemorate,”

while each day the light goes around it

like a prowling animal,

or the rain falls on it, or the wind blows into it.

It may be solid, may be hollow.

Bishop’s emphasis on imaginary “sea or cloud or sand” evokes MacIver’s structure, which, while seemingly based on a real domicile, is transformed through MacIver’s imagination into the painting it became. It is a shack that is both “homely” and “an artifact / of wood.” Even the objects captured by MacIver in “Shack” appear “carelessly nailed,” suggesting the desire to cherish something without becoming melodramatic. Indeed, MacIver’s painting “may be solid, may be hollow.” Bishop ends her poem with these words:

But roughly but adequately it can shelter

what is within (which after all

cannot have been intended to be seen).

It is the beginning of a painting,

a piece of sculpture, or poem, or monument,

and all of wood. Watch it closely.

The monument “can shelter what is within (which after all / cannot have been intended to be seen).” One wonders if what cannot have been intended to be seen, for Bishop and for MacIver, is the total mysterious interior of a person, hence why Bishop ends her later poem “Arrival at Santos” with “we are driving to the interior,” and why MacIver focused in her paintings on perception and perspective – the view through a window, the view across the water – and rarely if ever on perspetiveless abstraction. It is important to watch both of these artists’ works closely, because in their emphases on the ways in which we see, they create new ways of seeing, new poems, new dwellings, new monuments. These structures, however, are never separate from one’s own individual and idiosyncratic point of reference. Thus it can be concluded that Bishop and MacIver are equally as interested in objective truth as they are fascinated by subjective freedom.

____________________________________________________________________

WORKS CITED

Baur, John I.H. “Full Text of “Loren MacIver I. Rice Periera.“” John B. Watkins Company: New York, 1953. Web. 04 June 2014.

Bishop, Elizabeth. One Art: Letters. Ed. Robert Giroux. New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1994.

Bishop, Elizabeth. The Complete Poems, 1927-1979. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1983.

Costello, Bonnie. Elizabeth Bishop: Questions of Mastery. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1991.

Frankenberg, Lloyd. Loren MacIver: The First Matisse Years. New York: Alexandre Gallery, 2002.

Fountain, Gary, and Peter Brazeau, eds. Remembering Elizabeth Bishop: An Oral Biography. Amherst: U of Massachusetts, 1994.

Goldensohn, Lorrie. Elizabeth Bishop: The Biography of a Poetry. New York: Columbia UP, 1992.

Samuels, Peggy. Deep Skin: Elizabeth Bishop and Visual Art. Ithaca: Cornell U, 2010.

Zirra, Maria. “Cultural Memory, Ekphrasis and Slippery Surrealism in Elizabeth Bishop’s “The Monument”” Academia.edu. N.p. n.d. Web. 01 June 2014.

____________________________________________________________________

ANDREW FIELD has published essays at Thethe Poetry Blog and book reviews at The Rumpus. He has an essay coming up in the California Journal of Poetics, and this summer participated in the Ashbery Home School. He is a PhD student in English at Case Western Reserve.

____________________________________________________________________

Read more work by Andrew Field:

Review of Ron Padgett in The Rumpus.

Essay on John Ashbery in Thethe Poetry Blog.

Poems in Ohio Edit.