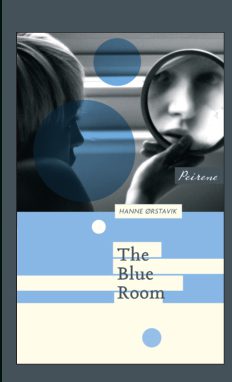

THE BLUE ROOM

(an excerpt)

The Blue Room

A novel by Hanne Ørstavik

Translated from the Norwegian by Deborah Dawkin

Published by Peirene Press

There’s a song I made up when I was a child and afraid of the dark. I used to sing it as I ran home. I’d count the number of windows I passed before the song finished and then start it over again. I used to pretend the song had no end, like a bubble, a perfect sphere, and so long as I was inside it, I was safe. I kneel in front of the armchair now and bend my back as low as I can, bow my head, fold my hands. Then I sing my song several times over, without stop.

The apartment was silent and in darkness when I let myself in. It smelt of smoke and something else, sweet, peculiar. It was only about eleven or eleven thirty. I wondered if Mum had gone out with Svenn. I walked through the lounge, to the curtain that divides her room off, and looked towards the big bed by the wall. The bedclothes lay in a bundle, making it impossible to see if there was anybody under them. Mum, I said quietly. No answer. I said it again. The duvet shifted, noises came from by the wall, it was thrown aside and Mum sat bolt upright, as though she’d been disturbed by a piercing siren. She rubbed her eyes. She was wearing her pink nightdress.

What’s the time? she asked. About eleven, I said. She turned towards the shelf on the wall, switched the little lamp on, found her glasses, checked her watch, took out a book and plumped the pillows up behind her. She shot me a glance over her reading glasses before opening her book, wondering perhaps if I had more to say. I saw she was halfway through one of those Swedish pocket editions. Göran Tunström, maybe. I turned and went into the bathroom, sat on the toilet with my eyes closed. When it’s late I pretend I’m already asleep. I thought about the sight experiments carried out on kittens. During the first months of their lives they were put in an environment where they were exposed only to horizontal lines. As a result they failed to develop any ability to see vertical lines. The hypothesis was that a lack of visual stimulus at key sensitive periods would hinder the development of important connections between the eye and brain, despite genetic potential. I opened my eyes and saw the lilac wallpaper, the blue walls around the bath, the black-and-white-striped shower curtain. I could hear Mum’s voice from the lounge, but not the words – the dividing curtain muffled the sound and I’d closed the toilet door. I wiped myself, got up and opened the door with my trousers down. Mum was walking towards me with her big round glasses on her nose, wearing her slippers from Granny and the old shawl I’d bought at a jumble sale over her shoulders. A man rang, she said. A short while ago. She looked at me with anxious eyes magnified behind her glasses. He said his name was Ivar. She spoke in a deliberate tone, as though she was warning me of some danger and wanted me to take everything in. I was suddenly gripped by fear. How had he found my number? She leant on the doorframe and watched me as I pulled up my knickers and trousers, did up the zip. Have you put on weight? she said. I turned to the tap, washed my hands meticulously. You’ve got my body, Mum said. The wide hips, the big knees. Karin sends her love, I said. My thoughts were on his voice: it had been here, on the telephone. Men find that irresistible, Mum said, a broad backside. Her brow was furrowed, as if she was thinking of something in particular. I cleaned my teeth with my right hand and stroked her hair with my left. It was dry at the ends. She ought to get it trimmed. Karin’s a bit… said Mum. A bit what? I said. Well… she said. Go on, say it, I said. She’s a bit… slow, isn’t she? said Mum. She took my hand and held it against her cheek. I smiled with the toothbrush still in my mouth. She squeezed my hand and sighed, then, keeping a tight hold of it, she looked at me seriously: This Ivar, Johanne, are you sure he’s right for you? Remember how relieved you were last time you got rid of that admirer of yours? Wouldn’t it be daft to get yourself involved again so soon? I didn’t know what to say. It wasn’t true that I’d been glad last time, that wasn’t how it had been. I’d never had a real boyfriend. I’d been in love, yes, last spring, with a post-grad economics student. We’d collided on the stairs, his books had scattered everywhere – macroeconomy – he’d smiled at me and our hands had met as we picked them up, like in a film, magical. I’d told her about it. Mum and I have agreed that she’ll approve any future husband. Her experience will prevent me from marrying a man who lacks boundaries, self-control and sensitivity. The social economist disappeared. I saw him in the canteen a few times, nothing more. I was sad, that’s how I see it now. I’d had so many ideas about how things might turn out. I studied for my exams like crazy, and did well, better than ever. I expect that’s what Mum remembered, the excitement over my end-of-term results. But it was she who was most pleased. And now I didn’t know what to say to her, it was all turning into a jumble, a fog in my head. I felt a pressure behind my forehead, in my eyebrow. Exhaustion, no doubt, after a long week of studies. Suddenly I was gripped by fear. Perhaps she was right. Perhaps Ivar was dangerous, a bad man, cold, manipulative, abusive. That look in his eyes, could I really trust it? And now he had my telephone number, he could easily find out where I lived. My back felt stiff. Mum took my hand, squeezed it again, and stroked it with her other hand. I looked at her nail polish, several layers thick. My dear, sweet Johanne, she said, the best girl in the whole world. Then, after giving my hand a final squeeze, she let it go and went back to bed. I closed the bathroom door, turned back to the mirror, spat into the sink, rinsed my mouth, then stared at myself, trying to find any concrete reason for anybody loving me. I thought about the development of babies’ sight. They seek contrasts between light and dark, and see best from about thirty centimetres away, the distance from the breast to the mother’s face. While the baby feeds, it studies its mother’s eyebrows, hairline and eyes, because those are the areas of greatest contrast. In my bed I lay straight out: I get to sleep fastest that way, flat on my back without a pillow, arms at my sides, like a mummy or dead child. I sank down and down, falling into a deep sleep, and as I was sinking I thought: Forgive me, Lord. Forgive me and bless me. When I was a child I used to think of something I was looking forward to, then concentrate all my thoughts onto that one thing. I remember wondering, on that Friday night, what I was looking forward to. What, Johanne, are you looking forward to? Through the wall I could hear the thudding of the bass, with the occasional solitary note or line of melody. Mum’s Walkman. She often turns up the volume and puts it on the shelf, so as not to have the headphones pressing against her ears.

____________________________________________________________________

HANNE ØRSTAVIK, was born in 1969 and grew up in Tana, Finnmark, in the far north of Norway before moving to Oslo with her family at the age of 16. Her first novel Hakk (Cut) was published in 1994 and her literary breakthrough came three years later with the publication of Kjærlighet (Love), which in 2006 was voted the sixth best Norwegian book of the last 25 years in a prestigious contest in Dagbladet. Since then the author has written several acclaimed novels and has received a number of literary prizes, including the Dobloug Prize, for her entire literary output, and the Brage Prize, Norway’s most prestigious literary award. Ørstavik’s novels have been translated into eighteen languages. The Blue Room is being published on June 12, 2014 and will be her first work translated into English.

____________________________________________________________________

About the Translator:

DEBORAH DAWKIN trained as an actress, and worked in theater for ten years. She has written creatively and dramatized works, including the poetry of the Norwegian Inger Hagerup. Other translations include Ugly Bugly and Fatso, both by Lars Ramslie and To Music by Ketil Bjørnstad, which was nominated for the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize. She has also worked with Erik Skuggevik on many translations from Norwegian, including Ingar Sletten Kolloen’s biography of Knut Hamsun. They are currently translating eight plays by Ibsen for the new Penguin edition. Deborah has an MA in Social and Cultural History and is working on a PhD on the translator, Michael Meyer.