The Banquet:

The Complete Plays, Films, and Librettos

By Kenneth Koch

Coffee House Press

634 pages

This is no ordinary book of scripts. Collecting for the first time all of the plays, librettos and television performances by New York School poet Kenneth Koch, The Banquet is an essential publication that rounds out our sense of Koch as a writer of profound and versatile talents. Even the label “script” seems ill-fit. These are bursts of charming joy, mystery, surprise and delight animated by a love of language and a deep belief in its possibilities.

Many of these texts are more poem than play, that is, their surprise and delight — and there is much of both throughout this collection — comes instantaneously rather than through the build-up of dramatic tension. Koch flouts the basic components of drama, including character development, narrative arc, and rising tension. Instead, he delights in language over the creation of character.

Yet there is profundity here in good measure. Little Red Riding Hood is a haunting revision of the classic children’s story, and stages darker possibilities for the inner lives of the characters. Just as fairy tales comment on human nature, Koch’s version incorporates the psychology of desire and fear. Arriving at her grandmother’s house, Little Red Riding Hood speaks:

As though there were

No lights at all, only the shadow of a light

Which shudders in the mind. Yet I remember

A dancing blood as positive as light–

I fled the dance; the storm had washed away

The road to home; I followed to this place

A shadowed path, as though my memory

Would blossom into sorrow in the light

As it does now–heavy and sudden.

These blank verse lines are on the more formal end of the spectrum for Koch, and create pockets of poetry in the uncanny existential atmosphere of this play, or “Entertainment in One Act” as Koch dubs it.

112 of these plays were collected in Koch’s 1,000 Avant Garde Plays, short situations that form the core of this collection. Often less than a page in length, these avant garde plays span civilizations and time. The Yangtse is representative of the scope and lyricism of Koch’s plays, and also of their, well, playfulness. It begins with the stage direction “The stage represents the entire length of the Yangtse River, or at least both ends of it.” In less than half a page, Koch dramatizes time, the power of nature and the nature of power. It is an impressive performance from a poet writing for performance.

In an interview with John Tranter, Koch spoke of the genesis of these avant garde plays:

After I published my Selected Poems and after I published On the Edge — two long poems — and after I published Seasons on Earth, I couldn’t think what I wanted to do next in poetry. While I had the time to do it, I wanted to do something more with the theater. And I decided to devote my entire attention to writing plays for a year or two. Which is what I did, with the One Thousand Avant-Garde Plays.

Rather than a pit-stop before Koch’s next poetic project, these plays are, in fact, what Koch did next in poetry. They are poems for the stage and the page, hybrid works that exist in both mediums at once. That is not to say they all lack traditional dramatic weight. In fact, some of Koch’s plays re-imagine classical theater in intriguing ways. There are no fewer than six versions of the opening of Hamlet’s famous “to be or not to be” speech. Smoking Hamlet, for example, consists of the first five lines of the speech, then the stage direction “HAMLET lights a cigarette, inhales, exhales, and walks offstage.”

But perhaps the greatest achievement here is The Construction of Boston, which manages a nearly impossible blend of surrealism and accuracy in a work that condenses and visualizes the founding of the great city of the Northeast. First performed in 1962 (which was, by the by, 17 years before Pink Floyd’s The Wall) as a collaboration between Koch and three visual artists, it is a rollicking creative jaunt in which “[Robert] Rauschenberg chose to bring people and weather to Boston; [Jean] Tinguely, architecture; and Niki de Saint Phalle, art.”

The people Rauschenberg brought to Boston were a young man and woman who set up housekeeping on the right side of the stage. For weather, Rauschenberg furnished a rain machine. Tinguely rented a ton of gray sandstone bricks for the play, and from the time of his first appearance he was occupied with the task of wheeling in bricks and building a wall with them across the proscenium. By the end of the play the wall was seven feet high and completely hid the stage from the audience. Niki de Saint Phalle brought art to Boston as follows: she entered, with three soldiers, from the audience, and once on stage shot a rifle at a white plaster copy of the Venus de Milo which caused it to bleed paint of different colors.

In his eponymous manifesto Antonin Artaud advocated a Theater of Cruelty that would reinvent theater to reawaken the audience’s sense of reality, allowing “the magical means of art and speech to be practiced organically and as a whole, like renewed exorcisms.” Koch’s is a theater of delight, not cruelty. Yet despite this seeming divergence, Koch’s plays fulfill almost exactly the demands detailed in Artuad’s manifesto:

The language can only be defined in terms of the possibilities of dynamic expression in space as opposed to the expressive possibilities of dialogue. And what theater can still wrest from speech is its potential for expansion beyond words, for development in space, for a dissociative and vibratory effect on our sensibilities… It is not a question of eliminating spoken language but of giving words something of the importance they have in dreams.

That seems an apt description of lines like these, spoken by NURSE in Without Kinship:

These modern gems have laziness.

My hat is his. This Denver sun

Shines on and down

What grassy slopes?

Season! here is the soap factory;

There is the charged balloon.

My grandfather at eighty offered

The stanza a million dollars

That could make him feel as though

He were really a lagoon.

His face is now seldom

More than unscientific explanation

For a rug. Oh, carry me, impossible slug!

(She lies down too and becomes driveway.)

Artaud’s program for the Theater of Cruelty includes “an adaptation of a work from the period of Shakespeare that is entirely relevant to our present state of mental confusion,” “a play of extreme poetic freedom by Leon-Paul Fargue,” and “one or more romantic melodramas in which improbability will become an active and concrete element of poetry.” Koch, an admitted Francophile, may have acted on these suggestions.

The Banquet is the perfect title for this collection, a book to be read and reread (and performed!). It is a Nantucket Basket of spirit and poetry for the stage.

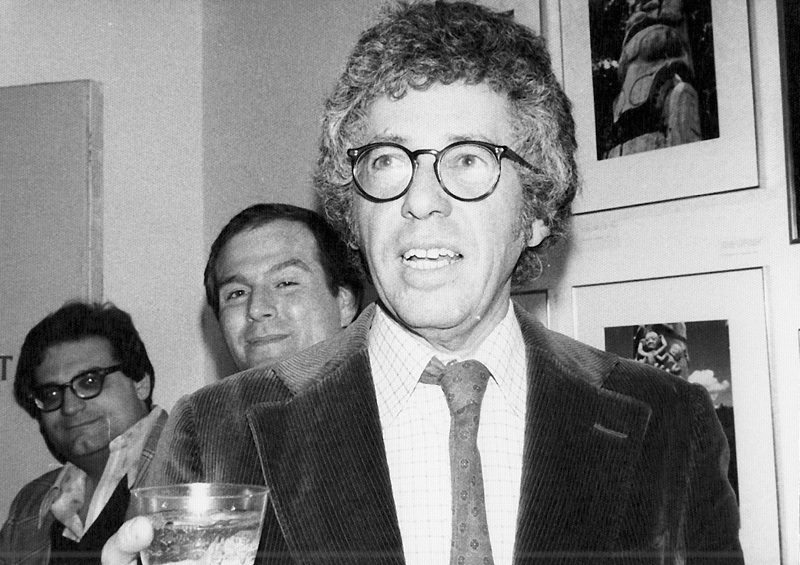

–Stephan Delbos