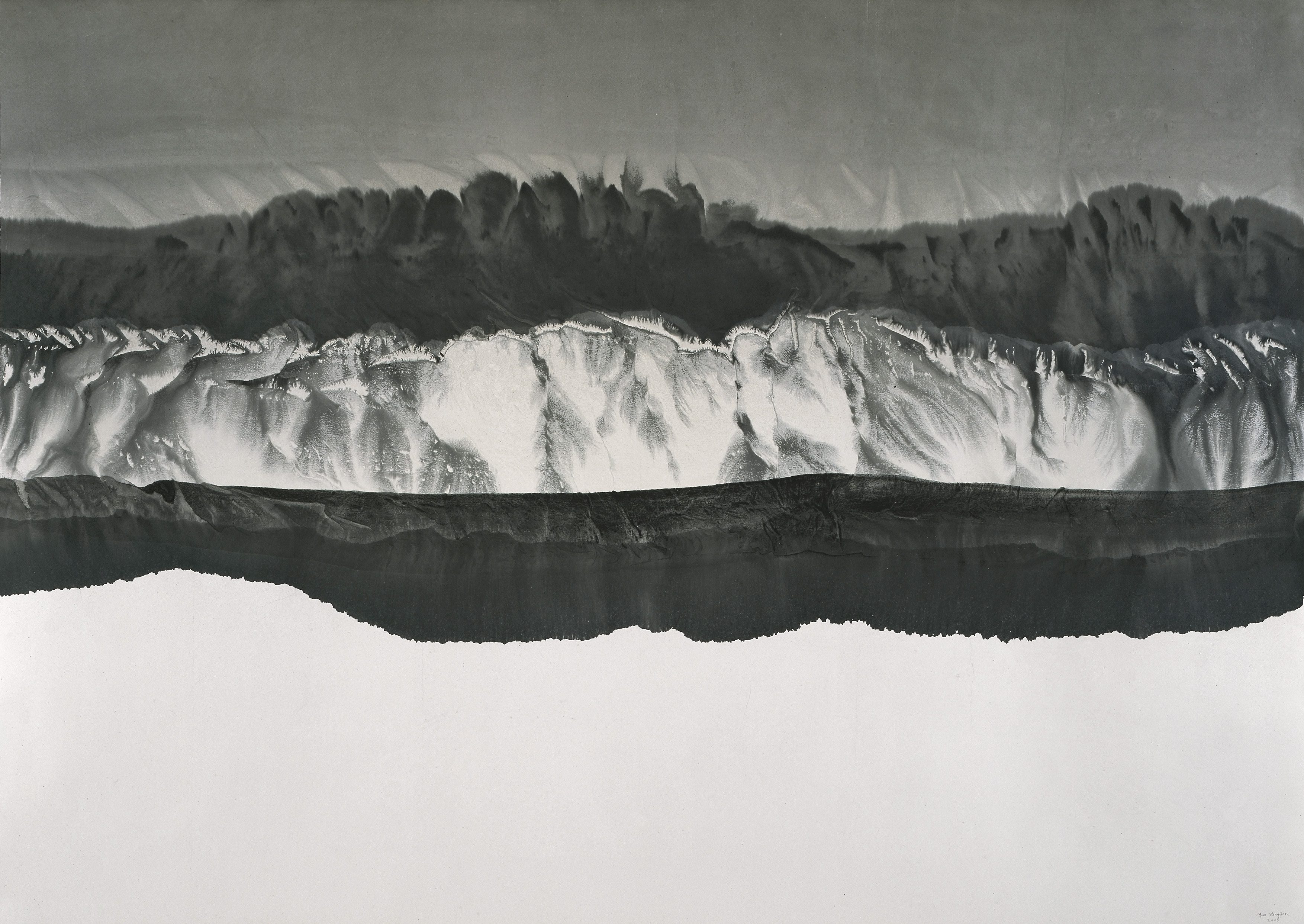

He Gong, “One Day All of Us Eat Cordyceps” (120cm x 150cm), 2013: Acrylic on Canvas

Editor’s note: This essay by dissident Chinese writers Yang Lian and Yo Yo, establishes a context for contemporary Chinese art that attempts “to move forward from the perception in the West of a contemporary Chinese art.” The essay, translated by Chen Jung-hsuan and Jacob Edmond and edited by Janet McKenzie, prefaces an exhibition of six Chinese abstract painters whose works are included in a special retrospective at Edinburgh’s Summerhall, from 2 August to 27 September, 2013: Liu Guofo, Guan Jing Jing, Yang Liming, Liang Qian, He Gong and Wu Jian. The exhibition, titled, Moving Beyond: Chinese Modern Abstract Art, seeks to “do justice to the diverse work being produced by artists who seek a deeper intellectual and spiritual standard in their work, a canonical basis for Chinese contemporary art.” The essay, first appearing in B O D Y, will be re-printed as part of the exhibition catalogue.

The Cultural Revolution officially ended in 1976. Yet over thirty years later the shadow of this so-called Cultural Revolution has not disappeared. Among Chinese artists, at least, it has become ever deeper. The difference is that this shadow was once clearly identified as a catastrophe, a disaster, whereas now it has become a seduction that alluringly fills the air. Beginning with the “Mao Goes Pop” exhibition held by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney, Australia, in 1988, “Cultural Revolution Pop” has achieved success as a brand in the market during China’s period of transformation from Cold War poverty to the extreme commercialism by an entire population.

It is not hard to see that the commercial exploitation of politics and official government propaganda are one and the same. The Cultural Revolution Pop Artists exploit the theme of Chinese politics. Behind the cheerful success of the phenomenon lurks the silence of those people whose lives were actually destroyed. “Post-Cultural Revolution” thought negates the logic of evolution because it contains not a single new idea outside of the Cultural Revolution. The power game of the Cultural Revolution is increasingly replaced by an equally insidious money game. If one gives up self-questioning, art becomes the same as plagiarism; by adopting the language of American or European art movements, Chinese art plays in to the hand of Western hegemony. Do artists have the right to steal and sell second-hand products simply because they are “Chinese artists”? If the autocracy prohibits you from self-expression, that is one thing. It is quite another if you have the opportunity to express yourself but have neither your own artistic language nor your own words, so that you have no alternative but to continue to use the modes of expression taught to you by the autocracy. “Cultural Revolution Pop” is itself a negation of artistic individuality.

The unbelievable impact of Mao, the exoticism surrounding the Cultural Revolution, and the unusual distance between China and the world in terms of geography, language and culture — all of these factors influence a person’s clarity of mind when judging values. The best way to obliterate a false value is to show the true value of a good work. Globalization has not yet changed the basic rules for the evaluation of art. What we are looking for from the perspective of multiculturalism is still the individuality and depth of a work— unique intellectual and artistic qualities, which cannot be borrowed. This has nothing to do with exoticism, but can only be presented through the concept and form of the work itself.

In the year 2000, Gao Xingjian became the first Chinese writer to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. His novel Soul Mountain, a story about the exiled human spirit, is an epic that employs continuous self-questioning, to link a range of texts from the great Chinese poet Qu Yuan’s masterpiece Encountering Sorrow to James Joyce’s Ulysses through a common underlying theme: a person must actively become “other” to him or herself. By distancing a subject from him or herself, art arouses creative energy. And in general, being an “active other” is the core issue for contemporary Chinese art. We face a world of others in all aspects. Here in the West, it is easier to understand the “visible other,” while in classical Chinese culture it is more important to be self-aware of the “invisible other.” Such an idea is well presented in the great number of modern ink-wash paintings created by Gao Xingjian over the years. When viewing his paintings, one cannot help at the first sight but be deeply drawn to their “oriental flavour”: the mountains, trees, clouds, water, indistinct objects, and dreamy people, all of which are floating and sinking in the water colours. A poetic sense is vividly portrayed through the partly hidden and partly visible images in the painting’s composition. But wait, is he imitating the classical painters or illustrating the clichés of “Zen”? No, what makes these works eye-catching is the sense of modernity that comes from the individuality of the artist. It is connected to the free-stroke mountains and rivers of ancient Chinese painting and to Western abstract painting. Yet by achieving a subtle balance between the concrete and the abstract, it maintains a distance from both. The “Chinese flavour” here is elevated to a spiritual level that is universally understood by all human beings. An “artistic other” has to be an “ideological other” first. The self-awareness of Gao Xingjian also derives from the depth of his independent thought. This “depth” of opposition is present in his pain at the loss of humanity in Chinese political reality. Inherent in his pain at reflecting on the loss of beauty when art around the world becomes obsessed with “revolution,” which eventually leads to a shallowness and emptiness of human spirit. He has a book about painting entitled Another Kind of Aesthetics. To emphasise the idea of “another kind” suggests actively distinguishing between different forms. As he stresses, art has to return to the feeling of sincerity. It has to go back to the individual who neither exaggerates nor is arrogant, but who insists on maintaining ultimate spiritual and artistic independence. He does not yield to the aesthetics of critics, nor does he care about the aesthetics of identifying (or being identified). On the contrary, he is looking for the aesthetics of difference, which he names “the aesthetics of artists.” His thoughts and individuality thus refuse to be simplified by any collective statements about politics, race, culture, and the like. They are projected onto his pictures, making every painting a landscape of the mind. Please take a look at the fluidity of the concrete and abstract images. Which ones are concrete and which ones are abstract? After looking at them for a while, one discovers, unexpectedly, the obscurity of the concrete images and the clarity of the abstract ones. They support and illuminate each other. Among the many layers of illusion, what appears is the variety of the real!

Gao Xingjian was born in the 1940s. In age, he belongs to the generation who completed their education before the Cultural Revolution, started creating works during the Cultural Revolution, and matured after the Cultural Revolution. Very few people from this generation were able to go far or deep along the road of being an “active other.”

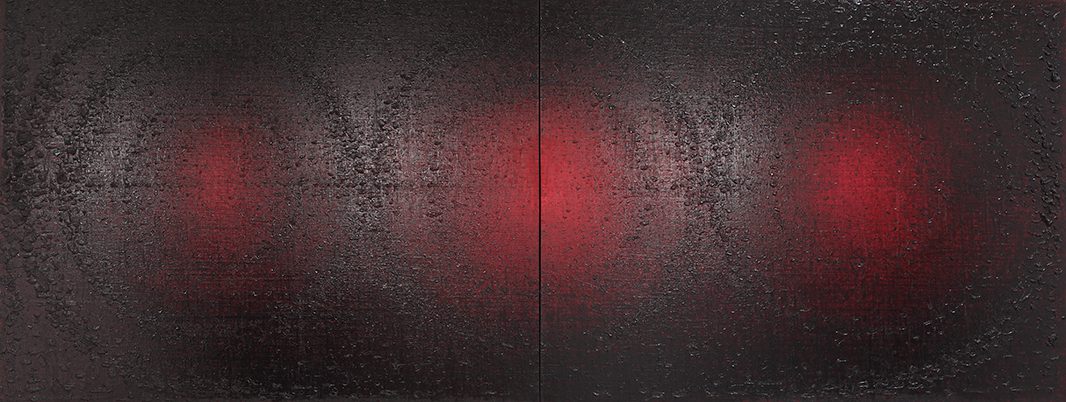

Yet Shang Yang is another artist from this generation. His painting series Dong Qichang Plan looks more like Western art. The colours and compositions, which are presented in the form of huge blocks, oppose the soft, muted tranquil beauty preferred in traditional Chinese painting. Brown and black are especially often utilised in his big paintings (which are over two meters long) to create a structure similar to strata. Do they suggest an earthquake? Looking at the paintings of Shang Yang, the viewer might feel offended or invaded because of their sharpness (Dong Qichang Plan––3) and suddenness (Dong Qichang Plan––29). Obviously, he does not care about comforting people visually. He twists, stimulates, and even infuriates aesthetic indolence and so enters a new visual realm. But (another turn!), by taking a closer look at Shang Yang’s works, one finds that they suggest exactly how modern Chinese people reflect on their tradition: they disobey it, refuse to follow its patterns, they question it, criticize it, link to it by going “the opposite way,” and create dialogues with it through resistance. Self-confidence allows one to dare to “resist” like this. “Tradition” as such is alive. Its life must originate in the creativity of individuals, through whom it never ceases to grow and develop.

Shang Yang chose Dong Qichang, a famous Chinese calligrapher from the Ming Dynasty, to name these works. The calligraphy of Dong Qichang is well known for its variety of styles and great skill, a spiritual bloodline to provide Shang Yang with deep inspiration?

If the Western concept of time is the primary theoretical basis of evolution, when thinking about the question in China you must keep in mind that you are facing a concept that is confusingly intertwined and multi-layered. Here there is no fixed, linear “order.” All Chinese and Western elements from the past to the present are presented “simultaneously” in front of every person, making you the selector or “orchestrator.” So what is the basis upon which an artist establishes his or her own order? Neither age nor time is important, whereas the depth of thought is key.

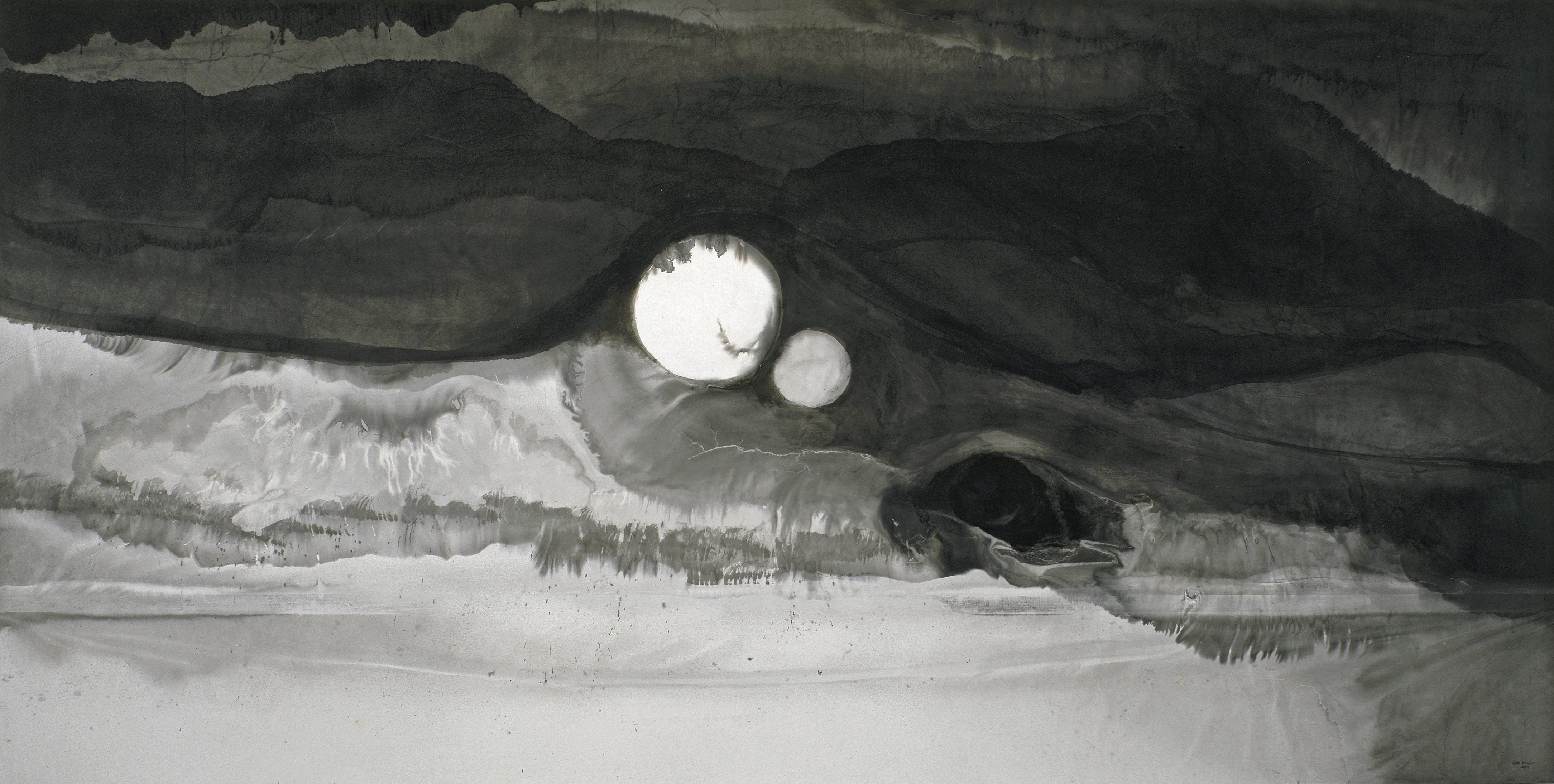

Guan Jingjing, born in 1983, is a distictive member of her generation. In spite of her age her thoughts are both sophisticated and sarcastic. She started painting in oils and then changed to acrylics. Whether it is the thick-textured oil paints or the comparatively subtly layered acrylic colours, she plays easily with them. She can make her colours as heavy as the dark clouds heralding a rising storm in the mountains; she can also make them as light as an unrolled silk cloth. Although a diminutive figure, she is skilled at managing huge paintings. During interviews, she is able to explain herself clearly and meticulously, although paradoxically she uses the term “Untitled” to name her paintings, as if she feels worried that any other title would restrict the sense of abundance she would like to present in her pictures. Examining the details of Untitled 08–04, what the viewer sees is not necessarily colour, but how the music or rhythm of the heart leaps from the “painting,” full of contrasting details. The huge black masses penetrate through heaven and earth. Taking a closer look at them, one finds that they are differentiated from each other with darker or lighter colour tones. The layered and changing colours in lighter tones emerge from between the dark fingers. Are the light colours falling into or struggling free of the dark ones? Guan provides the viewer with pure visual enjoyment. There is also a collision of thoughts that is deeper and stronger than the visual impact itself: that is yi! It can be yi for yixiang (image), yi for yiwei (significance; implication), or yi for yijing (artistic concept). Rejecting all the enticements of utilitarianism, art evinces the true poetics of an individual’s existence.

The most distinctive linguistic feature of the Chinese written language is its lack of verbal tense. When written down a forever-archetypal sentence structure turns historical time into simultaneous time, actions into situations, and specific ideas into abstractions. The concept of “simultaneous time” permeates people’s thinking, helping to create the reality of the now. In terms of art, we are confronted simultaneously by both traditional literati paintings and Western paintings. They do not require less skill from the artist; on the contrary, they set a higher standard, demanding an “active other” with many kinds of expertise—many kinds of self-awareness: command of the brushes and calligraphy used in Chinese painting and of the concepts and structures that are the special strengths of Western art. In a sense, if an artist today is able to paint a “traditional” literati painting, and his or her work can meet the standards of classical works in terms of theme, style, and skill, he or she is more likely to be perceived as a conceptual or experimental artist, rather than an old- fashioned artist.

He Jianguo is a good example of a representative of the “Neo-literati Painters” in the 1980s. His paintings contain old Beijing courtyards, ladies in traditional dress, flowers, birds, goldfish, shields, fans, cricket pots, and grape trellis, as well as the lines of calligraphy essential to traditional painting. No one can deny the work’s archaic character, but neither can anyone deny its modernity,” because everything has been changed by the artist, who has turned reality into his own realm. Aloofness and elegance––styles pursued by artists of classic literati paintings–become the “earthly daily routines” of common people’s lives, while this earthly flavour is transformed into something elegant through the popular folk colours––bright red and bright green. It is as if Huang Gongwang held a palette of Henri Matisse in his hand. It also looks as if Jing Nong of the Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou and Pablo Picasso got drunk together. The gracefully flowing lines and freely spread colours, abstract as they are, still look concrete. They are the product of outstanding skill and learning. Over twenty years ago, He Jianguo made a living by painting, and his works were once sought after. When commercialism transformed the Chinese art market He Jianguo responded with disdain, and refused to sell. He believed that market forces and the rush for Western recognition had caused artistic standards to collapse. His actions can be seen to preserve the traditional integrity of the literatus. At the moment, the small place in Beijing where he lives is literally a private museum filled with antiques. He and his wife Yan Ni live there quietly and contentedly. Is he “traditional”? Or is he “avant-garde”? Let’s return to Chinese words for inspiration: “simultaneous time!” Such is the literati’s consistent lifestyle and mode of thinking from the past to the present: there is no such thing as being “new” because nothing can ever be “old”!

How can the ancient Chinese cultural tradition modernize itself? Such a question is like a promise, or, more precisely, a nightmare that has tormented the Chinese people for over a century. Generally speaking, people always want to make a choice between Chinese and Western cultures. But classical Chinese culture has gone, and Western culture is still like a castle in the air. The more desperately one chooses, the worse it becomes.

An “active other” by contrast escapes this entanglement, transforming the theory/practice conflict between China and the West into “independent thought as theory and ancient and modern China and the world as practice.” This is precisely an assertion of the reality of the situation: the “tradition” for contemporary Chinese artists is not a purebred, but always a crossbreed of Chinese and Western elements. When we study a work, what touches us most deeply is often not its expressive skill but the process of decision making that is continuously taking place within the artist’s mind. This is artistic process, but it should also be seen as a life activity, because establishing an artistic message requires establishing meaning in one’s own life. With such a meaning, the mind remains steadfast and true, even when faced by the noise and confusion of a crisis. Such a horizon of thought is illustrated in the works of the great calligrapher and ink-wash painter Zeng Laide. Zeng uses the brush as a metaphor for heaven, paper as a metaphor for earth, and ink as a metaphor for humanity, returning to the concept of a universe comprising heaven, earth, and humanity found in traditional Chinese ink-wash paintings. Re-departing from the origin, the artist seeks complete freedom for his visual elements through the depth of his calligraphy and artistic forms. His works of “huge landscape” and “big art” stretch through heaven and earth, and the pictures are filled with cloud and smoke, as if the fixed strokes of the ancient Chinese characters had been expanded into a kind of “infinite calligraphy.” The visual shock goes beyond the meaning expressed in the Chinese characters and the form of the calligraphy: departing simultaneously from both classical Chinese freehand brushwork and Western abstract painting, it arrives directly at writing’s and painting’s shared spiritual existence. Despite a multitude of different engagements in his paintings, Zeng’s artworks must be taken as a whole. The unknown spaces in the pictures appear perfect, heavenly, as if they could be no other way. These are not “external” landscapes for us to admire and copy; they are complete in themselves. And when they turn to examine us, they are like all the world’s masterpieces examining their intellectual forerunners.

The drawings and oil paintings of He Duoling are extremely powerful. In his famous works of the 1980s, such as The Spring Breeze Awakes and The Crow Is Beautiful, the tranquil atmosphere and melancholy style of the paintings do not conceal the abundant maturity of his skills. In his exquisitely charming strokes, heavy and modest colours, and extremely refined compositions live the nineteenth-century Russian masters with their deep love for nature and history; the tradition of West European painting as “opened up” by the American natural world in the twentieth century; and the Chinese literary tradition with its long-lasting bloodline from Qu Yuan and Du Fu, to our post-Cultural Revolution generation. He Duoling deserves to be known as “the painter who has read the most poetry.” He evinces the truth of this statement by turning himself into a painting and his life into poetry. In this way he “lives himself into” the Chinese literati’s several thousand year old spiritual tradition. After the 1990s, he shrank from the “post-Cultural Revolution” theme, which had become commercially hyped by the Chinese art market, while continuing to explore his own themes and style. Here it may even be too limited to continue using the idea of the classical “literatus.” What we see is that he uses oil colours to paint the fog and mist, among which a sleeping newborn baby is partly hidden and partly visible (The Baby). With water-ink-like uneven strokes he crochets a net that snares a fairy-like naked girl (the Rabbit series). He even returns to the eternal theme of flowers and plants, yet by rendering them blurred and saturated he makes us doubt what we see: are we viewing an expressive impressionist work or could it be dreamily fine brushwork (the Sketch of Miscellaneous Flowers series)? In these late works, one finds no sign of other masters but only the artist himself. The “subject matter” is no longer important and neither is concreteness or abstraction. But the artist’s skill shines forth brightly from every corner of the canvas, giving him the freedom to bring mind and image together in perfect unison. What I want to say is that they are united in a kind of taste that might be called “bitter elegance.” Mind, thought, and hand are all indispensible here. Not only are the paintings visually “beautiful,” but, more than that, they possess the “beauty” of a philosophy sublimated from pain. In passing through various phases, He Duoling’s creativity has become increasingly clear as his artistic powers have grown, and the result is powerful. It allows me to articulate the issue clearly: what is the “meaning” in these artworks that is deeper than artistic “meaning”? If the artist controls the brush: who then controls the artist? It is not difficult to answer the question. The music from his brush follows and approaches the old teaching of Confucius from over two thousand years ago: shi yan zhi (poetry speaks the mind). Here shi suggests the broad meaning of poetry, and zhi means the aspiration of the mind. The word yan (speaks) points to the nature of expression– through which art makes the internal external. The masterpiece presents no more and no less than the self of the artist.

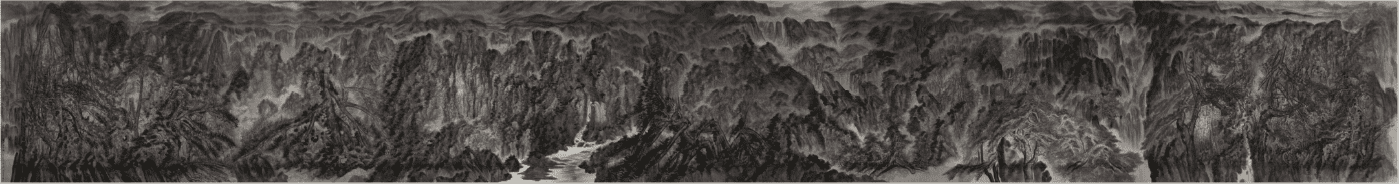

When we first saw Xu Longsen’s brilliant and massive works, the word that came into my head was not “art,” but “thought.” It would be inadequate to talk about the work of Xu Longsen in terms of form, style, or skill. To give you an idea of the space his work occupies, his studio in the Dongfeng Art district in north Beijing is literally an aeroplane hangar. On entering this space, the viewer feels tiny. On one side of the room is the 12-metre-high, 11-metre-long: A Mountain Never Rejects Its Height and the other by the 26-metre long, 5-metre-high Tao Models Itself after Nature. These huge ink-wash paintings immediately destroy the possibility of measuring them by conventional standards because their size is so vast that a small brush even when fully dipped in ink would produce an almost invisibly fine line. To create a picture of the high “mountains” towering like giants that Xu so admires, one needs to abandon all traditional skills, or in other words, thoroughly rewrite and recreate them. But this is merely the first level at which he sets a challenge for himself in his painting.

The second level is more difficult. His goal is not to destroy tradition. On the contrary, by destroying traditional skills (or rendering them completely ineffectual), he demands that art as a whole be reconstructed in a completely different realm and in a way capable of reconnecting it with the traditional spirit that permeates Chinese culture. He does not want only to destroy but to build anew, to establish a new point from which form can evoke the spiritual. To realise such an idea in painting requires an infinitely unfolding abstraction that nevertheless also gathers connections and interactions together in concrete forms. In Tao Models Itself after Nature the viewer is overwhelmed by the groups of mountains with thousands of valleys, the huge sky with scattered clouds, and the tall pine trees among layers of stone. The vastness of it is like a tsunami of ink and brush or a black and white universe that continues to explode when you move, exposes further different angles. Then the examination of “detail” poses new challenges: How does that strange pine tree hang upside down in the air? How do those scattered stones transform into mountains, sea, and sky? How does the artist splash and sprinkle on Mi Fu style ink dots that are bigger than entire paintings by Mi Fu? How does the artist create the sophisticated layers of colour tones, a task that exceeds even a “masterly style”? Xu Longsen demands complete structures for each part of his painting; and the overlaying of structures creates a multi-dimensional whole. This is indeed Tao Models Itself after Nature because nature really is communicative and interactive in this way––it is “holographic” and free. This is not a concept of “history” built on linear time. This is countless possible times, along with countless possible eyes, that continuously build and erase universes, and then build and erase them again; the number is infinite! The idea is also like the verb in written Chinese: it would be too narrow to consider it to lack tense, because it actually contains all kinds of tenses. This space eliminates the small cottages and people found in traditional landscape paintings, but bears the weight of the fundamental fates of all human beings. It speaks directly of both reality and nothingness. The word “thought,” which came into my head, is exactly the consciousness of existence. The size of Xu’s work is not restricted to the size of the wall. What it requires is a “depth” of thought that, by combining Chinese and Western art without one asserting supremacy over the other. We once summed- up contemporary Chinese poetry in a single short sentence: “Begin from the impossible.” We also summed up the distinctive features of contemporary Chinese art in two terms: “conceptual” and “experimental”. Without any existing cultural forms to follow, we can only create brand new ideas with which we try to experiment in every painting or line of verse.

Xu Longsen’s uncompromising stand enables him to shift from the physical preoccupations of every artist, (style, medium) artistic thinking to a philosophical level. Each brush stroke is at once filled with the great pain, sadness, and happiness of life. This includes his persecution in adolescence, his experience of political lies in adulthood, and his eventual comprehension of the essence of classical Chinese culture: the deep beauty of sadness. In the long poem, (Yi), which took me over five years to write, there is a line that runs: “The only true birth is birth in the form of death”; in another long poem, “Narrative Poem,” which took me over four years to write, there is a line that reads: “Beauty is to fall in love with impossibility itself.” It took Xu seven years to complete Tao Models Itself after Nature ––this kind of extreme work requires this kind of complete, concentrated devotion! We admire the extreme position of Xu’s work for only a spirit like this is able to inspire others. Xu and we got to know each other after he discovered an article of mine. When he read the words “contemporary Chinese artists need to be thinkers and they have to be great ones,” he insisted that we met. Those who share the pain and beauty of real thought are destined to come together.

The works discussed in this essay can be distinguished from Political Pop and Cynical Realism, irrespective of generation, from the individual choice of each artist. Whether profound like the works of Gao Xingjian, powerful like the works of Shang Yang, abundant like the works of Guan Jingjing, elegant like the works of He Jianguo, immense like the works of Zeng Laide, sophisticated like the works of He Duoling, or extreme like the works of Xu Longsen, these works have in common both individuality and depth. They do not idealize a specific place, for each place exists within the self. They refuse exoticism, because the global world requires more than superficial images, using a borrowed language. Nowadays, who is not a compound of mixed cultures–the ancient, the contemporary, the East, the West, the South, and the North, all of which are interacting unceasingly in one person? The only problem is: are they interacting in a positive way?

The “tradition” of any single culture has lost its potency; in our globalized world, there is only one “big tradition” for all to share. In such a tradition, individual thought and artistic depth create a kind of formula that makes works multi-dimensional and continuously “comparable” to each other. We have to make comparisons in terms of the artists’ strictness in self-questioning, the necessity of their contents and forms, and the achievements of their works. History reminds us that ancient Chinese poems always remain new; it is their intellectual and artistic depth rather than their age that makes the works able to withstand numerous re-interpretations. Against the corruption of humanity and degeneration of taste, which have spread like viruses beyond national boundaries, we have no other choice but to turn each work into an “artistic thought project.” Calmly and self-consciously we make ourselves into castles, or to use my own words, “towers built downwards”: by questioning our own lives and the meaning of existence, we resist the false life lived without heed to the crisis in thought. Through self-questioning creation, we can resist the merely decorative. Through the impact and endurance we find in challenging ourselves, we affirm the value of authentic art. Authenticity can form an individual artistic resistance, capable of resisting the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution and the widespread powerlessness following the Tiananmen Square uprising in 1989. Borrowed images and media from Western art cannot assuage political impotence and the spiritual void experienced by so many people in China, even if the market promises a financial return.

In the art of Gao Xingjian and Xu Longsen individuality and art evoke spiritual concentric circles. The circle of the great tradition has been formed by individual acts of artistic resistance, throughout Chinese and world history. At the centre of this circle, we see Heavenly Questions, written two thousand three hundred years ago by China’s first poet, Qu Yuan. Heavenly Questions comprises a string of nearly two hundred, ever more penetrating questions ranging from the beginning of the universe, mythological history, and political reality, to the self of the poet. Yet there is no single answer. Step outside the Post-Cultural Revolution: Chinese artists have no alternative but to take the first step on this the journey that began long ago.

— Yang Lian and Yo Yo

About the authors:

YANG LIAN is one of China’s foremost contemporary poets in exile. He has published eleven collections of poems, two collections of prose and one selection of essays in Chinese. His work has been translated into more than twenty languages. English titles include Where the Sea Stands Still (Bloodaxe, 1999); Yi, a book-length poem (Green Integer, 2002); Concentric Circles, another book-length poem (Bloodaxe, 2005), Riding Pisces: Poems From Five Collections (Shearsman, 2008) and Lee Valley Poems (Bloodaxe, 2009). He is the co-editor of the anthology, Jade Ladder: Contemporary Chinese Poetry, published in 2012 by Bloodaxe Books. He lives in Berlin.

YO YO is the author of seven collections of prose, including two collections of short stories, four novellas, and a non-fiction book on the history and culture of Eton College, where she has taught. Her novel, Ghost Tide, was published in English translation by HarperCollins in 2005. She was born in western China but, along with her husband Yang Lian, has lived abroad since 1989. She lives in Berlin.