I saw Jack Gilbert once, though I never heard him read his poetry.

It was the winter of 2006. Snowy Amherst, Massachusetts. Where Emily Dickinson lived, wrote and died. Gerald Stern was giving a poetry reading in a venue I can’t quite recall, other than to remark it seemed the type of place for AA meetings. Brown folding chairs. A card table in the back with paper tablecloth, red plastic cups, hard imitation M&M cookies and three-liter bottles of Pepsi.

Gilbert was living in nearby Northampton, where he had settled in his late years. There was a rumour he might turn up at the reading. He and Stern had grown up together in Pittsburgh, and though there was also a rumour that they’d had some sort of falling out, there was another rumour they’d buried the hatchet. Beyond rumour was Stern’s magnificent poem “The Red Coal” which documents, in Stern’s unique, heavenly blasé voice, the beginnings of his life in poetry and his friendship with Gilbert, and also comments on the disparity of their fates, as Gilbert met with immediate fame after winning the Yale Younger Poets’ Award for Views of Jeopardy, published in 1962, while Stern continued to write in obscurity.

“The Red Coal” begins:

Sometimes I sit in my blue chair trying to remember

what it was like in the spring of 1950

before the burning coal entered my life.

…

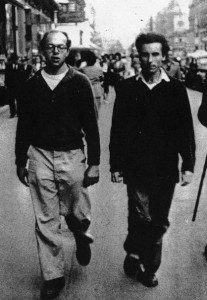

I didn’t live in Paris for nothing and walk

with Jack Gilbert down the wide sidewalks

thinking of Hart Crane and Apollinaire

and I didn’t save the picture of the two of us

moving through a crowd of stiff Frenchmen

and put it beside the one of Pound and Williams

unless I wanted to see what coals had done

to their lives too.

…

I think of Gilbert all the time now, what

we said on our long walks in Pittsburgh, how

lucky we were to live in New York, how strange

his great fame was and my obscurity,

how we now carry the future with us, knowing

every small vein and every elaboration.

The coal has taken over, the red coal

is burning between us and we are at its mercy—

as if a power is finally dominating

the two of us; as if we’re huddled up

watching the black smoke and the ashes;

as if knowledge is what we needed and now

we have that knowledge. Now we have that knowledge…

The symbol of poetry, the red coal, reminds one of the coal the angel touched to Moses’ tongue. It is a burdensome wound, a knowledge that cannot be undone.

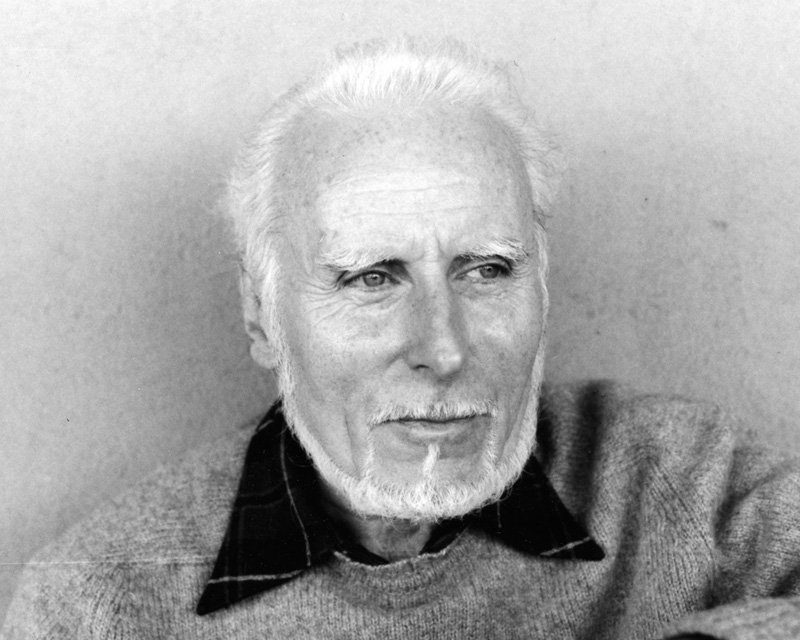

Gilbert did come in that night, just before Stern began to read. He was frail, wispy, but sharp still, his white hair a kind of purer brilliance in the neon-lit room. He was wearing a thick green wool sweater, and was surrounded by several people who seemed to be there just in case. He and Stern greeted one another warmly, in the way of old men who can mutually appreciate one another’s survival. Gilbert sat, and the reading began. Stern read “The Red Coal;” a kind of meta-moment, when poetry spoke to life and life replied. Afterward, Gilbert signed a few copies of Refusing Heaven, which had been published the year before. I’d left my copy at home. The poet left into the stout Amherst night, the snow, the street lamps like great fires hovering above the black-ice streets.

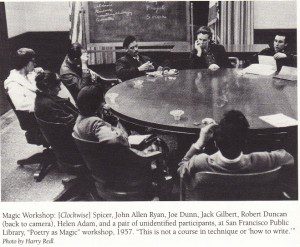

In 1957, living in San Francisco, Gilbert attended the poet Jack Spicer’s workshop, “Poetry As Magic.” In order to be accepted, Gilbert would have filled out a questionnaire designed by Spicer, who wrote: “This questionnaire is designed to indicate whether you can write poetry…Some of the questions will seem bizarre or pointless, but it would be useful if you would answer all of them as precisely as possible.”

The questionnaire contained questions like: “If you had a chance to eliminate three political figures in the world, which would you choose?” “Write a paragraph about how the fall of Rome affected modern poetry.” “What insect do you most resemble?”

There is a dissertation’s goldmine in speculating how Gilbert’s poetics were affected by Spicer’s workshop. Gilbert was surely aware of the magic possibilities of poetry, and its function as an instrument that could record and represent the world as a collection of sparks, of visionary moments. It is a concept he captures elegantly in “We Are The Junction,” the last poem in his last book of new poems, The Dance Most of All, published in 2009. The poem ends with these lines:

When body touches heart

they together are the moon

in the silently falling snow

over there. Which is truth

exceeding, is the residence,

the sanctified, is the secret

closet and passes into glory.

Gilbert’s poetry is full of such glimpses. Moments where something almost graceful is revealed, and assumes mythical status among a life of other nearly indistinguishable events. Sometimes these moments evoke bliss, and sometimes urchin grief. “Michiko Dead,” which Gilbert wrote following the death of his wife Michiko Nogami, is one example of the latter. Using a conceit, the poem equates grief with “a man carrying a box:”

that is too heavy, first with his arms

underneath. When their strength gives out,

he moves the hands forward, hooking them

on the corners, pulling the weight against

his chest. He moves his thumbs slightly

when the fingers begin to tire, and it makes

different muscles take over. Afterward,

he carries it on his shoulder, until the blood

drains out of the arm that is stretched up

to steady the box and the arm goes numb. But now

the man can hold underneath again, so that

he can go on without ever putting the box down.

The sureness of Gilbert’s vision here is startling, as is his mastery of language, evidenced by the grave presence of the poem on the page (resembling, of course, a box), which nevertheless retains fluidity through Gilbert’s purposeful enjambments, as in the first to the second lines above. This compressed sonnet has been intensely pressurised, just as the man’s grief has been internalized, and forced into the cramped space of the box.

Gilbert’s visionary glimpses can, and do, take place almost anywhere: While sleeping on the ground in Greece, playing the triangle in grade school, walking through snow in Copenhagen, or reconvening with friends who have just visited a French whorehouse, as in the poem “Music is the Memory of What Never Happened,” published in The Great Fires (1994).

We stopped to eat cheese and tomatoes and bread

so good it made me foolish. The woman with me

wanted to go through the palace of the papal

captivity. Hazley and Stern said they were going

to the whorehouse. That surprised me twice

because it was only two in the afternoon.

…

They said

how neat and clean it was in the whorehouse,

and how all the men and most of the women had

been in the fourth grade together. I remember

the soft way they said it but not what they told

about going upstairs.

…

I regret

the fresh coolness when they went inside from

the July heat and everybody talking quietly

as they drank ordinary wine in that promised land.

Gilbert’s poetry itself is a kind of promised land, offering passage to spiritual and emotional landscapes that are rarely accessed in contemporary poetry. The strength and insistence of his voice, the sureness of his craft, the heft and solidity of his poems on the page, these are marks of a master.

Jack Gilbert’s death is a true loss for American poetry. His finest poems are indelible.

—Stephan Delbos