B O D Y editor Christopher Crawford reviews three new pamphlets from Blue Diode Press, all by writers from or based in Scotland. Each pamphlet showcases a different approach to form, voice, and subject, and highlights the range and richness of the work being written in Scotland today.

Esther by David Kinloch

David Kinloch’s Esther is a bold, richly imagined work that gives voice to the Scottish calligrapher and miniaturist Esther Inglis. Part dramatic monologue, part play, the pamphlet shows a woman negotiating identity, language, and power in a world that sees her mostly as a craftswoman or a curiosity.

Set around the year 1600, the play places Esther at a moment of political tension, as James VI of Scotland works to position himself as the next ruler of England. She starts to suspect that her carefully made devotional books are being used to serve the King’s campaign, without her knowledge or consent.

Kinloch’s handling of voice throughout Esther is remarkable. She speaks in a mix of Scots, English, French, and even playful nonsense-like sounds, giving us someone torn between cultures and roles, but also full of fight. The language shifts feel true to someone trying to be heard in a time and space where they have no agency.

There’s real invention here. Not just in the script-like format and imagined staging, but in the way Kinloch brings together history, gender, politics, and art-making without ever reducing Esther to a symbol. She’s funny, devout, proud, angry. And she’s aware of the compromises she makes to survive. That complexity is what makes the book work so well.

There’s also a deeply moving thread running through the book in the figure of Esther’s son. His illness adds a raw, emotional charge to the work. We see how much is at stake for her. Not just pride or recognition, but survival, family, and love. Her books become a way of fighting for his life, a kind of desperate hope disguised as gifts or tributes, which adds another layer of urgency.

Some readers may find the linguistic density a touch disorienting, especially at first, and some may find the dialogue a little hard to “translate” into standard English. But once you lock into Esther’s rhythms, it becomes absorbing.

This is an ambitious piece of work. It’s also a layered meditation on the act of making — books, letters, identity — which Kinloch handles with wit, craft, and a keen sense of what it can cost.

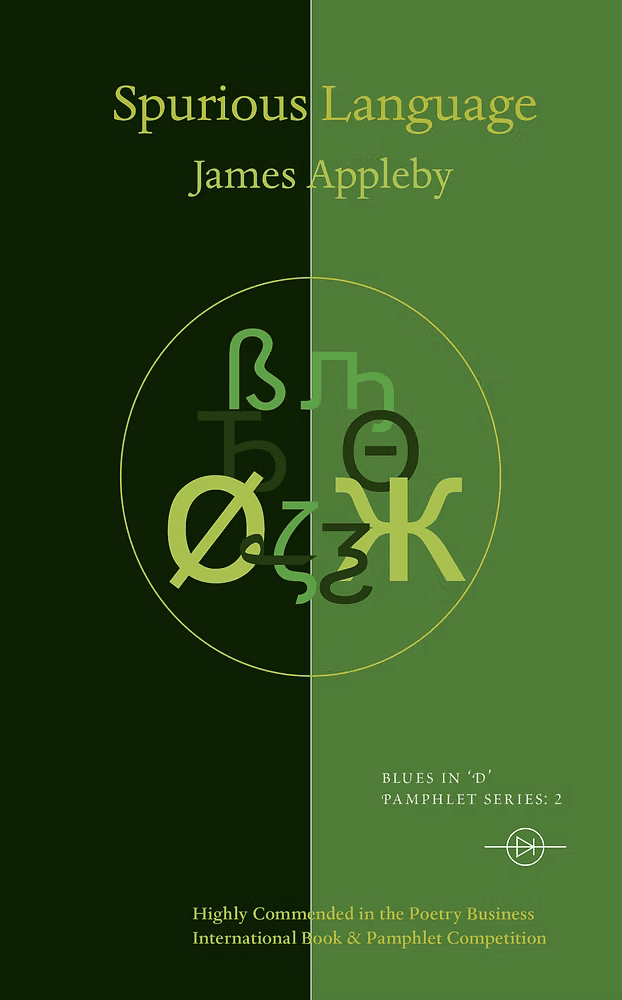

Spurious Language by James Appleby

James Appleby’s Spurious Language is sharp, inventive, and full of energy. These poems move fast. They think out loud, change tack mid-line, and constantly test the limits of language. Some are strange or funny, others more lyrical or searching, but they all share a deep interest in what happens when words break down, or when they almost hold.

Appleby has a knack for turning abstract ideas into something immediate. The opening piece, “Spurious Language,” sets the tone: a whirl of imagined grammars and strange communication systems that somehow still stay grounded in something real. Other highlights: “Tip of the Tongue” and “Letter to César Vallejo” get closer to the emotional centre, where miscommunication becomes not just a philosophical puzzle, but a wound.

A standout poem, “The Man I Saw Dead in the Road Reproaches Me,” highlights Appleby’s capacity to pivot from humour to pathos without losing control, as well as his ongoing obsession with how communication fails to capture real, lived experiences:

“In all your poems, which I think are shit,

I never joke. I’m your age, but we never get a beer. Always this cordon

between us —

there was no cordon. You could’ve sat next to me.”

And:

“Another lie is that we’re speaking English.

Talk to me in Spanish—I know you can. This didn’t happen in your cold

heartland, forensics putting up a tent. There were vultures.

Not poem-vultures.”

There’s plenty of intelligence here, but what stands out most is the range. Appleby can shift between essayistic musing and tight, image-led lyricism without ever losing his voice. At times, the density of linguistic inventiveness — wordplay, conceptual layering, and meta-poetic turns — risks overshadowing emotional immediacy. But this same inventiveness is also what gives the collection its distinctive voice and intellectual thrill. It rewards re-reading and close attention.

Appleby, who is also a skilled translator, is a talent worth watching. There’s a sharp mind working behind his poems and he’s capable of stretching language in unexpected ways.

Wander by Sophie Cooke

Sophie Cooke’s Wander is a quietly beautiful collection of poems: measured, attentive, and full of atmosphere. Also a novelist and short story writer, Cooke moves through solitude, grief, and natural space with a kind of deliberate stillness, but never feels static. These are poems that don’t need to raise their voices to leave a strong impression.

Cooke’s language is pared-back, but carefully shaped. There’s no rush to these poems. Instead, they walk at their own pace until they start to form a rhythm you can feel under the surface. What’s most impressive is how much emotional weight she’s able to carry without ever overstating it. In part, it’s this restraint and skillful use of tone and pacing that gives Cooke’s poems their emotional power.

Many of these poems feel like they’ve been carefully shaped, smoothed down to their essential parts. Cooke’s voice isn’t distant, but it keeps a kind of respectful hush, often turning inward before gently reaching back out to the world.

A poem like “Hermitage” shows this beautifully. The speaker lives alone in a rain-soaked shelter, slowly becoming part of the landscape:

“there is even soil between your ribs now

in which ferns grow.”

It’s a quiet but powerful image of how solitude and time let something new take root. Like much of the book, it shows how the natural world isn’t just a setting, it’s part of the speaker’s inner life.

Another highlight, “A Human Map”, captures the quiet wonder of walking without a map and still finding your way:

“it feels like a celebration, this sudden expanding

and opening, of more-than-enough, inside the wood.”

The poem reflects one of the book’s central ideas: that wandering isn’t about getting lost, but about opening yourself to different ways of moving through the world. It ends with the speaker reflecting on what it means

“to walk at least part of the animal way – even if

the path that is meant for you is the human one:

wider, leading always on, promising

to return you to a place you can be at home in.”

That mix of instinct and intention, of choosing a path while staying open to what’s off it, runs through the whole collection.

The steady tone across the collection may seem understated, but it creates space for something deeper to emerge: a slow kind of attention that mirrors the landscapes it moves through, and the inner movements it quietly tracks. The emotional range is wide, but never dramatic; the poems hold space for grief, change, uncertainty, and also flashes of comfort or clarity.

Wander is a quiet book, but a resonant one. It trusts the reader to stay with it, and rewards that with poems that echo long after you’ve finished reading them.

— Christopher Crawford