Photo: Yann Pocreau

Sarah Wendt, originally from Prince Edward Island, Canada, trained as a dancer and musician. Her work has focused primarily on performance and includes numerous collaborations with visual artists, musicians, and choreographers. Touring performances include Scream Choir, a choral performance co-created with Coral Short, and The Lead Apron, a solo for dancer and French horn player with Chloë Lum & Yannick Desranleau.

Pascal Dufaux, born in Marseille, France, is a sculptor and media artist. Prior to collaborating with Sarah, he presented solo and group exhibitions across Canada and internationally, including at Images Festival in Vevey, Mapping Festival in Geneva, Lab30 in Augsburg, Germany, at the Künstlerhaus Büchsenhausen in Innsbruck, Darling Foundry in Montreal, and Solway Gallery in Cincinnati.

They began merging their practices in 2017, forming the duo Wendt-Dufaux, which now forms the core of their artistic work. Their shared practice unfolds as a continuum of experiments, with themes evolving through mutual influence and exchange.

Their projects have been presented in museums, artist-run centres, and performance festivals across Canada, Europe, and the UK. Recent solo exhibitions include Miel du Temps at the Musée d’art de Joliette, Joliette, QC (2024); Clairière at Circa Art Actuel, Montréal, QC (2025); Études Ectoplasmiques at L’Écart, Rouyn-Noranda, QC (2023); and the Mountain moves while my fingernails grow at The Rooms, St. John’s, NL (2022). Performances and collaborative works have been presented at Take Me Somewhere Festival, Glasgow, UK; FURIES Festival, Marsoui, QC; VIDEO///PLAY in Montreal and Brussels; and at Theater Kampnagel in Hamburg, DE. They live and work in Montréal.

B O D Y’s art editor, Jessica Mensch, recently caught up with Sarah and Pascal in their studio in Montreal this spring to talk about their recent solo show, Miel du temps, at Musée d’art de Joliette, in Joliette, Quebec. The following interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

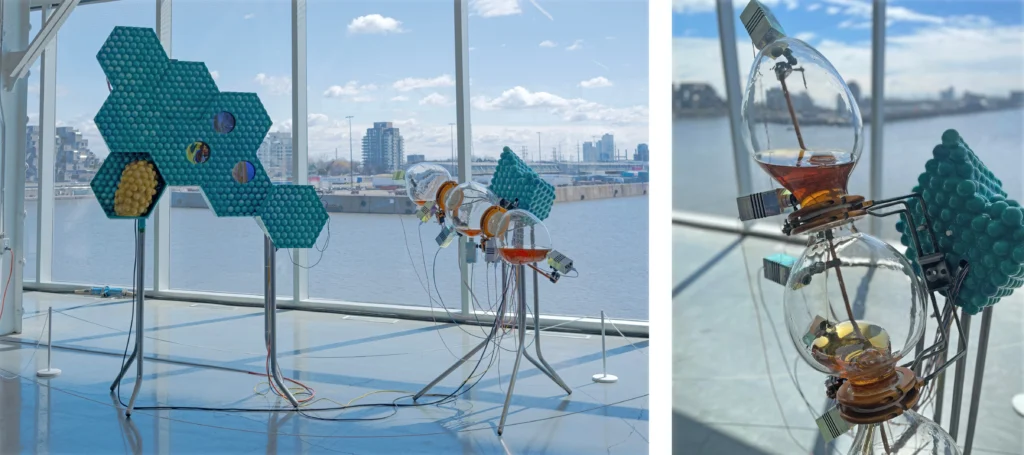

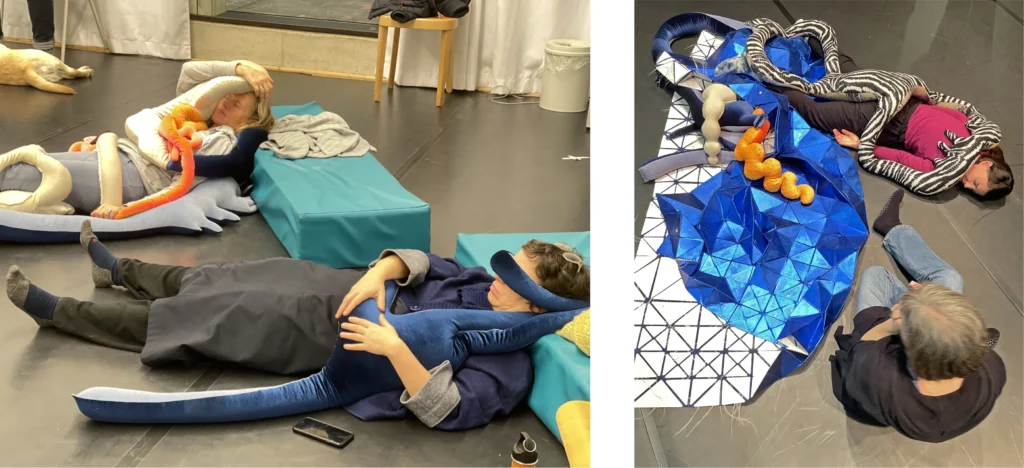

B O D Y: The way you displayed your work in the Musée d’art de Joliette suggested anthropological museum displays or habitat dioramas. I’m thinking here of your soft sculptures hanging from a metal armature in a semi-enclosed space (see image 1). Or the pink “tactile table” (see image 3) that was like a museum display model, albeit of an alien organic material. And of course, the metronomic apparatus that mechanically moved honey between three glass decanters (see image 4 and 5). Its contents projected onto the facing walls for your inspection and contemplation.

There’s also something very psychedelic about your forms, colours, materials, and sounds that takes what we’re meant to be observing and reframes it as being part of an alternate, less familiar, reality. Does this resonate with you?

Pascal: I think that our real subject is always way too large to enter in the space. We’re kind of, let’s say, trapped in the limitation of our own economy as artists. So, we don’t have the means to build a complete architecture. Like in Joliette, the subject is time and our relationship to time. The only thing we can do is to bring a symptom of that, of the manifestation of time. I like the idea of a symptom in the sense that a symptom is a manifestation of a force. It could be a force that is invisible, but the symptom is the part that is visible. I think that what we try to do is to make visible forces or events or things. Time, you know everybody is aware of time, but how can you show time? It will always just be a symptom. You’re going to show a trace. I think we are always aware that the end goal is to sculpt the perception of people. So that’s why when you work with music and activity, in the end it’s a way also to create a specific experience in the head of the viewer.

Sarah Wendt: I feel like we’re always trying to guess at it. I feel like I work a lot with flashes of things in my head. For example, I wouldn’t necessarily think “this is going to evoke a feeling”; it’s more like I try to reproduce images that I see in my head.

B O D Y: So, you look at the object and it presents itself to you in a very specific way?

Sarah: I think because I work with someone else, it gives me a lot of permissions… like an integrated dramaturg, as they say in dance and performance. A dramaturg or an integrative outside eye. Also, Pascal is usually able to figure out how technically he can do what I’m seeing. Sometimes an attempt is really to find multiple ways. I think we’re both very interested in mediums and disciplines, or how we can do the same thing in a drawing as in a sculpture, and in a video, and a space, and a performance. So, we have these repetitions.

The way that we got interested in multi-sensory work for people with non-typical, or atypical sensory perception, is kind of interesting in that it intersects with our general interest in how people see and feel and sense things. By activating even more senses, it has expanded how we can hopefully convey an idea or what we’re trying to do.

B O D Y: Does this relate to your ideas on craft – that craft entails the use of many senses, and in this respect, it’s a very progressive way of relating to the world around you. Perhaps even futuristic?

Pascal: It’s interesting how, most of the time, the feedback that we get from our work frames it as future oriented…It’s interesting because for us, it’s the present, it’s not the future. So, I always love when people see that in the work because it gives me a good temperature of their brain, and because talking about the future is something that is very open. And the idea, also, that the future might not be the future that is being dreamed of by the corporation, the oligarch, and all that. It’s this idea of taking back what the future could be, and maybe the future is actually very crafty and not just slick. It’s not just a black box where we don’t understand how things have been assembled.

Maybe it’s like going back to … I don’t like the idea of going back, it’s not going back. It’s more like …

Sarah: Maintaining.

Pascal: Yes, maintaining this relationship… What makes us human is this connection between the brain and the hand. This is how we manifest. Our intelligence is there. Forget about AI. This is another thing. Intelligence is really this amazing connection, or not just connection, but … It’s about translation. Translation of brainwave in the movement of your hand.

Sarah: That’s very connected to how I’m working too. Coming from a dance and music practice people struggle to consider me as a visual artist. There’s something about when you do a certain amount of your career in one discipline, like I did with dance, even though I’ve now spent an equal amount of time having a studio practice and sculptural practice, people, peers etc. have a hard time letting go of my identity as a dancer-performer. So, my way of being fine with that is to understand how I translate my dance practice into what we make in the studio, and the decisions I make compositionally.

B O D Y: Composition in terms of physical composition?

Sarah: Physical space, time, tempo, visual choices, musicality. A huge part of my dance practice was in the world of improvisation which is all about compositional training. You’re training yourself to make a piece, not in advance, but in the moment. So, you’re making a piece, and you’re finding a beginning, middle, end, and you’re using compositional tools. So, I use that same bag of tools when I make a drawing, or when we compose space, or when we make an installation. It’s all being translated. It relates to craft, somehow too. When your body knows a movement, it’s similar to the somatic knowledge or technique of drawing.

B O D Y: When you talk about craft, what you mean is this kind of relationship of the body to the material world?

Pascal: Yeah, it’s almost like this three-component relationship. When Sarah was explaining about the performance, the manifestation of an idea through the body. So, you have an idea, and the end is going to manifest that idea in relation to a certain type of material, and this material is then going to give you feedback on the idea. So, it’s a constant loop between the material – how the material is going to react, how your mind and body open to new ideas, because, for example, the material may not work the way you expected. It’s a dialogue.

Sarah: So, this morning, we were in the studio starting a new project… (Sarah points to a large weaving of yellow carpet that covers one wall and floor of their studio). We’re making a large-scale weaving. We are working on weaving an entire room this way for our next exhibition at CIRCA Art Actuel in Montréal, titled Clairière (Clearing).

Pascal: I think that weaving is a good symbol of what we were talking about, this relationship between the hand, the brain, and the material.

Sarah: Also, what’s so important to our practice is our studio. We have this space where we can come in. It’s about… experimenting. There’s quite a bit of research that we do here. Some of it’s never seen. It’s a lot of experimenting, a lot of trying out things.

Pascal: To see how material reacts.

Sarah: Reacts to each other, to other bits. One of the things Pascal was doing just this morning was laying out these (Sarah points to a pile of carpet tiles) …and he put this varnish on top of the fabric. So, we’re always mixing …

Pascal: And the varnish is going to react in a certain way …

Sarah: We’re experimenting to find the one we want to work with. I guess that’s a part of the craft, too. There’s a certain amount of knowledge needed to work with materials, to see how they can be woven together, for example… We’re always delighted when somebody talks about craft CGI in our work.

B O D Y: Craft CGI?

Sarah: Yeah, like this piece, for example, on the wall. People think, “Oh, is that CGI? Is that special effects?” And we’re like, “Oh, no, those are actually tapestries handmade through a lot of steps, that are then being manipulated by dancers and then filmed in some very basic ways.

Pascal: I think what we love in that is the reaction. In society today, who owns the magic? It’s the big corporation. When you go see a film, the aesthetic of the film is based on visual effects. And so, as an artist, when you don’t have access to all this big money, you don’t have access to magic. So, for us, it’s really important that we say, “No, we own magic. We can do magic.” I find it very interesting that we are able to obtain this type of magic by doing it DIY. I think all our work aims to reappropriate the idea of the future, the idea of magic, and to not let the big corporation be the only one that has the right to decide what’s going to be the future. Every individual owns the future. We cannot just let a big corporation decide what’s going to be the future. So that’s why we like the idea of DIY CGI.

Sarah: Also, I think you can feel a work that has taken many hours to make, too. You can feel the difference when something has been cut out by hand or …

Pascal: Yeah, it’s the repetition of a lot of gestures. It’s the care. For us, it’s very important to not be trapped in the idea we have of craft as being a way of doing things that’s from the past and in opposition to high-tech, and all that. To say, “they are crafty”, “it’s crafty” is still very patronizing. So, it’s not just a repetition of a technique from the past, it’s more like, how can we develop a craft of today? Which means developing the “intelligence” of your hands, which is the radical opposite to Artificial Intelligence.

Sarah: There’s something gently political about it, too. Our first show we called Quelques Parts dans l’inachevé, which translates to “Somewhere in the Unachieved”. We’re really curious about the ‘not quite finished’, ‘some amount of failure’, or ‘not perfect’ kind of space or feeling. The possibility for uneasiness – not serious discomfort, but a little bit of a question mark left at the ends of things.

B O D Y: What is your relationship to the unknown in your work?

Sarah: I feel that a lot of art is becoming too analytical, where everything has a specific reason why you made this choice, that choice, and that choice. I think what we’re searching for and what I really want is… Something you can feel, and you get this visceral experience that raises a question, but you don’t get the answer. Nobody’s going to come and say, “Well, I chose this material because it relates to blah, blah, blah, blah”. I’m just not interested in that. When all the questions are answered it’s really uninteresting. It’s not across the board… but the thing that I don’t like is that people are getting this really specific education that then changes the way they make art, so there is no unknown. The unknown is important for us. I think it’s just something we’re attracted to. I mean, we love David Lynch, and he leaves a lot of raging unanswered questions. Also, we love the weird. We love the strange.

Pascal: Art is a portrait of the mystery of life, you know, and life has no definitive answer. One day we’re just going to die. This mystery is so profound and deep, and it’s absurd, beautiful, and all that. As artists, that’s where we want to navigate. We don’t want to refer to what a critic is saying at an institution. That is a learned system created by an organization, by a certain type of organization that says, “that’s how today we should do art”. It’s wrong. It’s just practicing a methodology that has been dictated. It’s very important to manifest a critic against that, against all systems that try to remove the mystery. We are all connected because of this mystery. We have in common this question, this unanswered question about what the meaning of existing is, or to be alive …

— Jessica Mensch