Edited by Marco Sonzogni

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2023

704 pages

Famous Seamus. Shameless Hussey. These are just a couple of the insults we’ve seen on Facebook commenting on the tenth anniversary of the death of the Irish Nobel Laureate in literature. What is it about fame that makes other poets venomous? No matter. Arguing against the accomplishments of Seamus Heaney is like yelling at a mountain: it’s as immovable as it is unavoidable.

Heaney was a total poet. And a fine, committed translator too, as this new collection amply illustrates. His translation projects were impressive in scope: in addition to Irish-language poems, which ring with a sense of national identity, this book contains translations from Czech, Greek, Italian, Romanian, French, German, Russian, and Old English, among others. The latter is found in Heaney’s deservedly lauded translation of Beowulf, the full text of which is included here, along with the sprawling Sweeney Astray, an Irish folk poem.

There are too many highlights to mention, but Heaney’s renderings of several short, anonymous poems from the Irish are particularly charming and all the more so for likely being unknown to casual readers:

Birdsong from a willow tree

Whet-note music, clear, airy

Inky treble, yellow bill–

Blackbird, practicing his scale.

It is remarkable that such an accomplished poet and critic would also have been such a skilled and prolific translator, but this was undeniably the case. Illuminating notes and a chronology from editor Marco Sonzogni provide important context to this side of Heaney’s work, showing how his prize-winning translations formed an integral part of his writing, and also explicating different versions, publication histories, and backgrounds about how these projects came to be.

More than simply a volume for Heaney completists, The Translations of Seamus Heaney is a milestone for all lovers of world poetry and a fine example of how the poet’s calling can include not just pulling inspiration from personal experience, but also guiding poetry from other languages into one’s own.

— Stephan Delbos

Donna Stonecipher’s latest collection, her sixth, may just be her best yet. And that’s saying something about a prose poet widely considered one of the boldest and deftest contemporary innovators of the form. Long before this collection was published, poet John Yau raved about it in Hyperallergic. Reading it now in this handsome edition from Weslayan, it’s easy to see why. Each poem, a single prose paragraph, invites the reader into a state of attention not unlike a dream, or a hallucination, where every detail is sharp and clear enough to be real even as it dissolves right in front of you.

Throughout its 64 numbered sections, The Ruins of Nostalgia details the various spaces of urban landscapes in decline, drawing attention to the ephemerality of their features. Stonecipher is interested, in particular, in the objects we take for granted, that we see as permanent because they have endured in a way that suggests permanence relative to our own short lives. It makes sense, then, that the first of these “ruins” are found in museums, each museum being a site of memory, history, and preservation:

We had seen the bracelets made of the beloved’s hair, the Kaiserpanorama, the pneumatic tubes, the hourglasses, the shreds, the microphones hidden in the toupees, the ticking, the gilded mirrors reflecting our faces, the two rooms eight people lived in, the eight rooms two people lived in, the shreds, the trays of frangible butterflies carrying freight, the silvery clepsydras, the ticking, the simulacra, the shreds, the vitrines, the velvet ropes, the idealized portraits of the powerful, the blurry photographs of the powerless, the shreds, the erasures, the eras, the sureties, the ticking, the pink façades, the upward mobility, the shreds, the plunging fortunes, the downward spirals, the ticking, the springs of hope, the ticking, the ticking, the shreds, the shreds. We had been to the museum of the ruins of nostalgia.

From there, she journeys into the world outside, a space where the urban and nature collide, where four deer stand “poised down in a valley” as a train passes by “like four artworks in a museum” — a scene as ephemeral as anyone can observe, a moment in time, yet preserved in the museum of the mind. And yet Stonecipher’s project is no mere memorial to the things we’ve lost — or the things we stand to lose. Rather, it’s an interrogation of what it means to possess something, even for a moment. As she notes, there are many things we’ve lost that we don’t miss. “So would we really miss doctors and lawyers and accountants when the day came … when their expertise was surpassed by software?”

Nostalgia, for Stonecipher, is less longing than a deep, complex feeling of connectedness to things that are there but not there — things the mind creates when it wants to feel connected to the world, to situate itself within history, to grasp a sense of place beyond the confines of the skull. Its ruins are the lost objects it latches onto. Whether they still exist as physical items in the present is beside the point. The mind grasps for them in a time that is gone, the way each moment is a ruin of the moment that follows it. Stonecipher shows us that nostalgia is personal, individual, even when its references are public or collective. In this light, our obsession with the past — our nostalgia — is less about the past than the future that will eventually erase and forget us, too.

— Joshua Mensch

Translated by Jonathan Bolton

Blue Diode Press, 2023

66 pages

The first full-length collection in English translation from Petr Hruška, one of the Czech Republic’s greatest living poets, Everything Indicates includes 55 of Hruška’s prose and verse poems from previous books. An excellent introduction to a poet both charmingly plainspoken and delightfully mysterious, these translations by Jonathan Bolton should be required reading for anyone interested in contemporary European verse.

The book’s title poem is typical for Hruška, a prose poem revealing a moment of domestic intimacy and comfort that nudges against the unknown, threatening to open the void that lies just beyond our daily routines:

They are sitting there, flecked by the morning sun. Everything indicates that the woman will take away the mugs and then stay in the kitchen.

But suddenly she begins to talk about a blizzard in Switzerland. About gusts of wind shaking her young body so hard that she turned around, thinking it was a man’s hand. Amidst the madly whirling snow.

They sit in the sun, and he can’t understand: how it is possible he didn’t know about the blizzard in Switzerland until today.

Hruška’s writing demonstrates a hard-earned wisdom worn lightly and often depicts an individual at the crossroads of lived experience and uncertainty. His poems offer glimpses of mystery and communion with the unseen. Some have called his work surreal, but this does not do justice to his singular voice, which is uncanny yet more familiar than strange, and more interested in tracking the misalliance between outer and inner worlds than crafting stupefying imagery. This volume shows that Hruška’s work translates well to an international audience and that his reputation among Czech readers is justly deserved.

— Stephan Delbos

By Francesca Bell

Red Hen Press, 2023

96 pages

“Every two minutes, an American woman is raped,” begins the first poem in What Small Sound, Francesca Bell’s second collection of poetry:

her body forced open in the time it takes me to tear

this organic tomato to its pulpy center and bite in,

letting juice run down my chin, stinging.

The poem is called “Jubilations” and it deftly announces the twinned themes of this collection: appetite, desire, and passion for all that is good in the world on one side; violence, suffering, and the violation of the earth, the body, and the mind on the other.

Bell is a fearless poet in the truest sense of the word. But hers is not an autobiographical bravery — somewhat fashionable and altogether common these days. Rather, it is the bravery of a poet willing to risk tarnishing the beauty of her verse with the ugly realities of the world; to discomfort rather than reassure. The risks she writes about are real, existential, and frighteningly inescapable. And yet, it is through her exceptional gifts as a writer that she preserves beauty in the writing itself: her lines are clean, balanced, clear, marred by neither polemic nor pretension.

The book’s title, What Small Sound, refers to the sounds her ears can no longer hear. The title poem takes place in an audiologist’s booth, where clutching for sounds, she thinks about the distant moons of Jupiter, which she is “afraid to look at through the telescope, the stillness out there strong / enough to suck me in.” Between those distant moons and her body lies the rest of the world, the shared universe of humanity clinging together in the vastness of space. What makes it difficult to see such sharedness is the fact that we each inhabit our own version of the world. As one celebrates, another suffers, each blind to the reality inhabited by the other.

Yet the world Bell inhabits is one we’re all familiar with: random, cruel, and dangerous, but also remarkable in its beauty and its capacity for joy. The book is dedicated to her mother, “who made the path I walked into the world,” and who died this year from injuries sustained in a car accident. Bell is alert to the irony: with as sure a hand as she can manage, a mother guides her children into and through a world she knows she cannot control. The path ahead is lit by a desire to see the world as a place where beauty can be found. But to see beauty, one’s eyes must be open. To hear music, one must listen, even to the sounds one wouldn’t mind losing.

— Joshua Mensch

A Sanatorium Journal

By Max Blecher

Translated from the Romanian by Gabi Reigh

Twisted Spoon Press, 2022

166 pages

The Illuminated Burrow: A Sanatorium Journal is the first appearance in English of the final prose work by Max Blecher, a crucial contributor to the Romanian inter-war avant-garde, who published in the leading French surrealist journals of his day before dying of spinal tuberculosis in 1938 at the age of 28. It will be followed next year by Twisted Spoon’s publication of The Transparent Body and Other Texts, a collection of Blecher’s poems.

This book describes Blecher’s stays in sanatoriums throughout Europe. But it is also a mad-cap interior adventure, a feverish flow of prose that moves from depictions of the routines of nurses and doctors and the suffering of patients to illustrations of Blecher’s rich and cataclysmic interior life, where violence and death often frame his daydreams and fantasies, including one where a group of police dogs take over a police station, imprison the policemen in cells and break into butcher shops at night to feast, only to be foiled by the fire brigade and hung from a tree on the edge of town, which just happened to be the spot where the narrator liked to relax in the shade.

There is a distinct Proustian interiority to Blecher’s writing here, as the narrator’s inability to get out of bed or accomplish anything without help forces him to delve into his own mind, his memory, and imagination to seemingly spontaneously unravel searching, haunting narratives that often use the surrealist method of sublimating deep-seated fears and desires into everyday objects. This, for Blecher, is life inside the body’s burrow.

As he writes:

When I shut my eyes – as I sit in the garden bathed in afternoon sunlight, or when I’m alone, or as my fingers lightly brush my cheek while in conversation – I always discover the same tremulous darkness, the same intimate and familiar cavern, the same burrow, warm and illuminated, flickering with shadows, inside my body, the substance of my ‘self’ lying on the ‘other side’ of the skin.

Blecher’s writing is a valuable contribution to European avant-garde writing. The Illuminated Burrow is uncanny, strange, illuminating.

— Stephan Delbos

Anders Carlson-Wee’s second collection, Disease of Kings, presents an interesting conundrum: a memoir of poverty by a man whose poverty was, by his own account, self-inflicted. Not through drug abuse or untreated mental illness, but because he quite simply didn’t want to work. Or rather, he refused to give his time to an employer, so time, instead of money, became the currency upon which he lived.

To support himself, the Wee of this collection sells his own scavenged furniture every few months (organizing fake moving parties), rents out rooms in his rundown rental, and roots through dumpsters for food, which he serves to the tenants of his bed and breakfast. When all else fails, he turns to his father for support.

This presents the reader with a troubling question: are we reading an account of a privileged man’s poverty tourism, or is it a kind of verse journalism? In a sense, it’s both and the tension this dynamic creates is central to how the book works. The privilege that enables Wee to sustain a lifestyle that substitutes dumper-diving for shopping and food-stamp scams for work, that allows him to fall back on his father’s handouts, also establishes enough distance between Wee the writer and his own experiences for him to report back with an almost journalistic detachment.

It also gives him time to devote himself to poetry, a form of labor that goes unacknowledged here but is clearly evidenced by the poems. Wee’s gifts, and the result of his work, are apparent here. The poems read easily, propelling the reader through the book with a steady voice whose music is swift and consistent. When he shifts to another’s voice, as he does in several of the poems, recounting stories he’s heard from others along the way, using their own manners of speech, the change is subtly but exactingly observed. It takes years to hone such craft.

In this way, the book speaks for itself — and reveals Wee’s real project, which is to shed all material comfort for his art. His poem, “Ambition,” crystalizes his thinking on the subject of material desire:

To suffer none of it.

Money, work, or obligation.

To face days free

of roles. No titles. No position.

…

To have stolen time. …

In the end, it’s about time, the currency that matters most to an artist. To have it is to be free. What Wee endures to achieve such freedom may be literally stomach-turning, but it points to an even more troubling dynamic within our own society. To be truly free, you must either have what you need beyond your awareness of it, or else the privilege to choose to do without it.

— Joshua Mensch

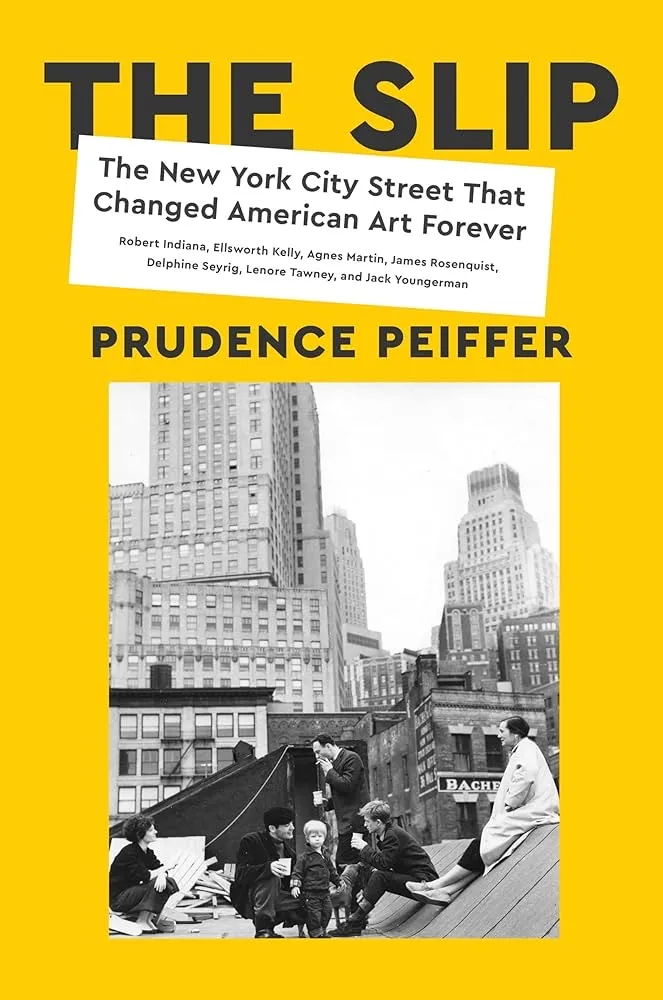

The New York City Street That Changed American Art Forever

By Prudence Peiffer

Harper, 2023

432 pages

Sitting easily beside other recent books of mid-century New York City art history, including Ninth Street Women by Mary Gabriel, Prudence Peiffer’s The Slip focuses on a particular neighborhood, Coenties Slip, a dead-end street at the south end of Manhattan near the water, a blip on the map that despite itself became a fermentative neighborhood for American art, housing the likes of Robert Indiana, Ellsworth Kelly, Agnes Martin, James Rosenquist, Delphine Seyrig, Lenore Tawney, and Jack Youngerman as they transitioned from obscurity to success. Several of these individuals would go on to be defining artists of the second half of the twentieth century, with styles spanning from the colorful avant-garde geometrics of Martin to the ubiquitous “LOVE” sculpture of Robert Indiana, which graces public parks, t-shirts, and postage stamps around the world.

Peiffer’s study takes place at street level. It is evocative of the neighborhood and its gritty genius loci in a way that few art history books are. She manages to be both gossipy and erudite:

‘Before Coenties Slip,’ Indiana said, ‘I was aesthetically at sea.’ The Slip offered a productive port. He absorbed everything greedily. ‘The front of number 25 was covered with words that influenced me in my work every day. Not just that; every boat, barge, ferry, train, or truck that passed nearby or on the river next to Coenties Slip, etched its markings into my work.’ He got two cats who never went outside; he would rinse out their cans of food and use them to mix his colors. He bought his art supplies at New York Central Art Supplies on Third Avenue.

This was the generation after the Abstract Expressionists, settling in the city just after the death of Jackson Pollock. Accordingly, they sought their own way of living and painting: “When Youngerman settled at the Slip, he didn’t go to Tenth Street meetings of the Abstract Expressionist crowd at the Club. The group at the Slip didn’t socialize in the same raucous, bellicose way. As Youngerman explained, ‘There was no Cedar Bar for us. Happily, because the Cedar Bar was the last of the whiskey and cigarettes, all of whom died young except for de Kooning. That was the end of that particular era of living.’ Or, put yet another way, “We were all a bunch of Protestants from the hinterlands, as opposed to warm New York Jewish people, like Rothko and Newman.”

The art world of mid-century New York City has been examined in depth by numerous scholars, so it’s difficult to imagine there will be many more full-length studies of the era. But Peiffer utilizes an interesting framework that illuminates the lives and works of a group of artists who needed to invent a new way of making art in the wake of the massive popularity of Abstract Expressionism. Their story is a lesson in creative determination and community.

— Stephan Delbos

A beautiful and harrowing collection of photos and prose covering a decade of work in some of the world’s deadliest and most tragic conflicts and crises by Hungarian journalist and writer Sándor Jászberényi, Ten Year’s Wars is both admirably timeless and depressingly timely.

From the Gaza Strip to the Arab Spring to the conflict between Russia and Ukraine to famine and disease in Africa, Jászberényi lived on the edge of violence, fear, and death. This book, coupling his photographs with his own prose, shows that his humanity only deepened in the process. His black and white photographs speak for themselves, at turns stark, threatening, warm, and affirming. It would be difficult for prose to stand up to the strength of these images, but Jászberényi is also an incisive writer who seems to effortlessly blend stony courage with tender insight into humanity’s seeming inability to stop destroying itself.

As he writes about the disappointing ending of the promising Arab Spring:

Across the region, tens of thousands died during the Arab Spring, but nothing changed. If anything, the situation got worse. However, down in the sludge of society, big lazy fish are moving right now. Something is smoldering, burning with a slow flame. If you listen closely, the silence will tell you that everything will blow up soon.

That is because there are too many people in the Middle East and the terror is too big. You die in the same dire circumstances into which you were born. Meanwhile, through your TV and smartphone, you can see how fancy life is in other places. Something will definitely blow up, as sure as the sun rises each day. It may take one year or five years, but it will happen.

The Egyptian revolution has its 10-year anniversary today. I’m sitting here in Cairo. I’m bald and I’m looking in the mirror, wondering what happened to the boy who saw the ground moving, the falling of Gods, and who hid his trembling hands in his pockets.

This book is haunting. Jászberényi is an excellent photographer and a writer of real power. Seek out his work.

— Stephan Delbos