Interview by Antoinette Karuna

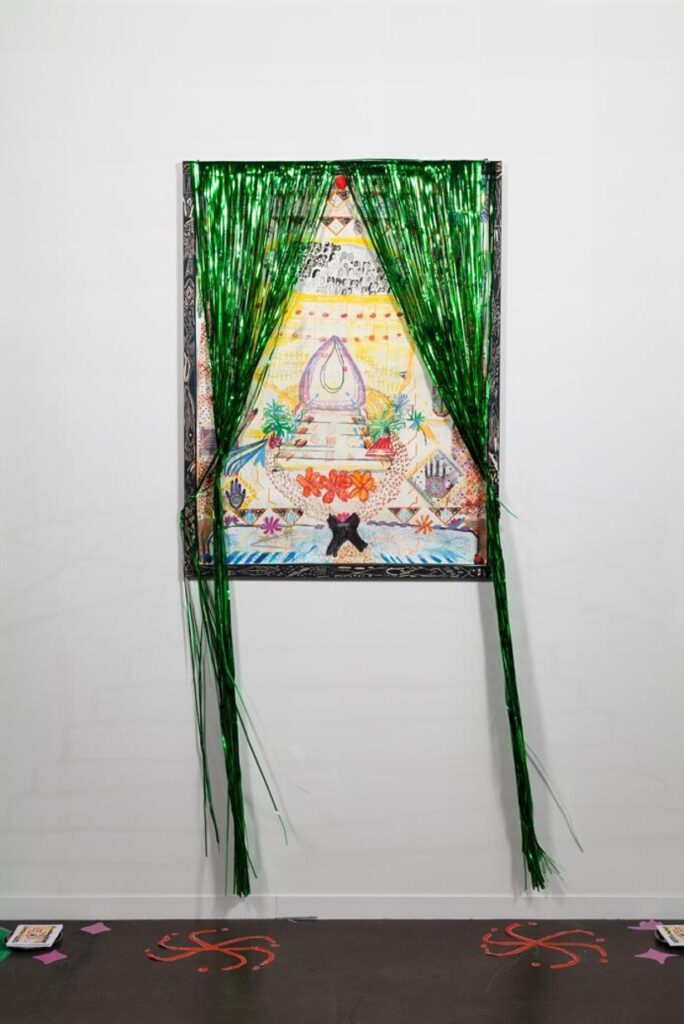

Padma Rajendran (she/her) (b. 1985, Klang, Malaysia) received her BA from Bryn Mawr College and MFA in Printmaking at the Rhode Island School of Design. She currently teaches drawing at Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, NY. Working primarily in printmaking, ceramics, and textiles, Rajendran creates complex and layered works that contemplate notions of home, homecoming, homeland, and gender. Her work has been exhibited at the International Print Center New York, Ortega y Gasset Projects (Brooklyn), Beers London (UK), Field Projects (New York), September Gallery (Hudson NY), BRIC Arts Media (Brooklyn), Aicon Gallery (NYC), Taymour Grahne Gallery (UK), SE Cooper Contemporary (Portland, OR) and has a forthcoming group show at the Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art (New Paltz, NY). Rajendran has completed residencies at Ortega y Gasset Projects, Mass MoCA, Women’s Studio Workshop, Ox-Bow, and Lower East Side Printshop. Her work has been featured in Chronogram Magazine, New American Paintings, Art Maze Magazine, and Maake Magazine.

I first encountered Padma Rajendran’s work in the summer of 2022 when I was online perusing South Asian diaspora artists working in textiles. I’m currently doing an MFA in Visual Arts at Memorial University, Newfoundland and Labrador, where I’m exploring my mixed-race identity as a South Asian Tamil and French Canadian person. I primarily work in textiles, and when I discovered Padma’s work, I was viscerally drawn to its visual language and emotional landscapes. I soon realized that Padma is also Tamil and, like my father, was born in Malaysia. Like me, she moved around internationally in her early life. I later wrote a research paper on her monotype series Sari Series, and through examining the visual language of these works, I learned a lot about our shared culture. As a mixed-race person raised far from my paternal South Asian family, my father bore the sole responsibility of transmitting his culture to me, and there are many gaps in my knowledge. Spending time with Padma’s work––and our subsequent discussions––has helped me fill in some of these gaps.

— Antoinette Karuna

B O D Y: Hi Padma. Thank you for taking the time to chat with me! Can you start with discussing the trajectory of your practice––from drawing to printmaking to textiles, including ceramics and other media along the way?

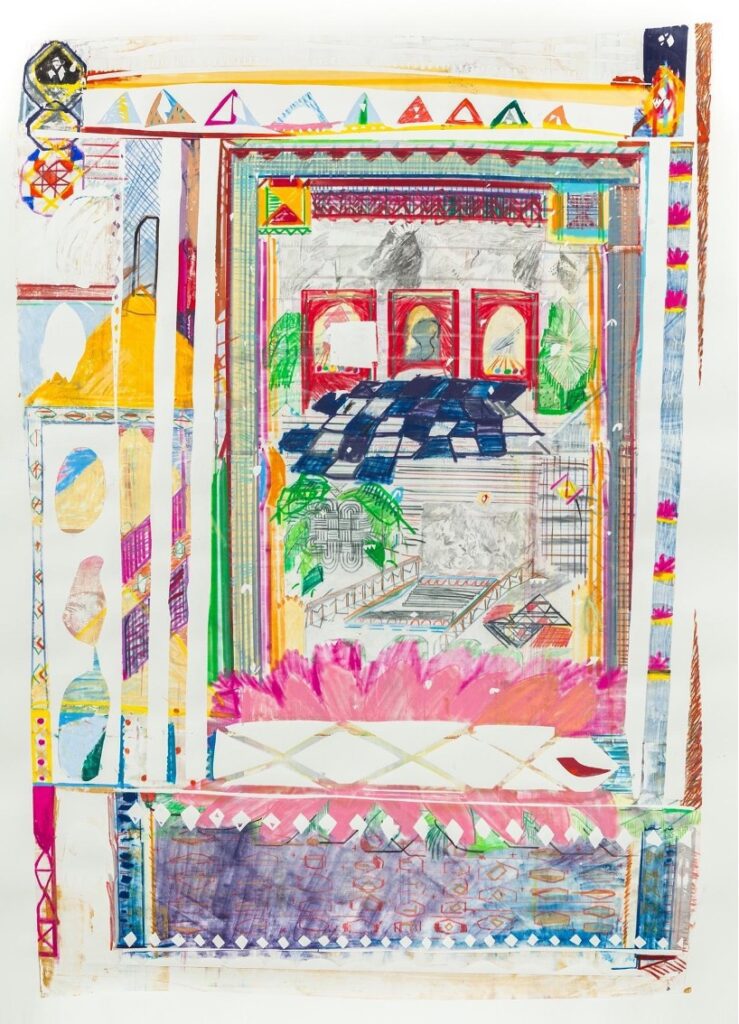

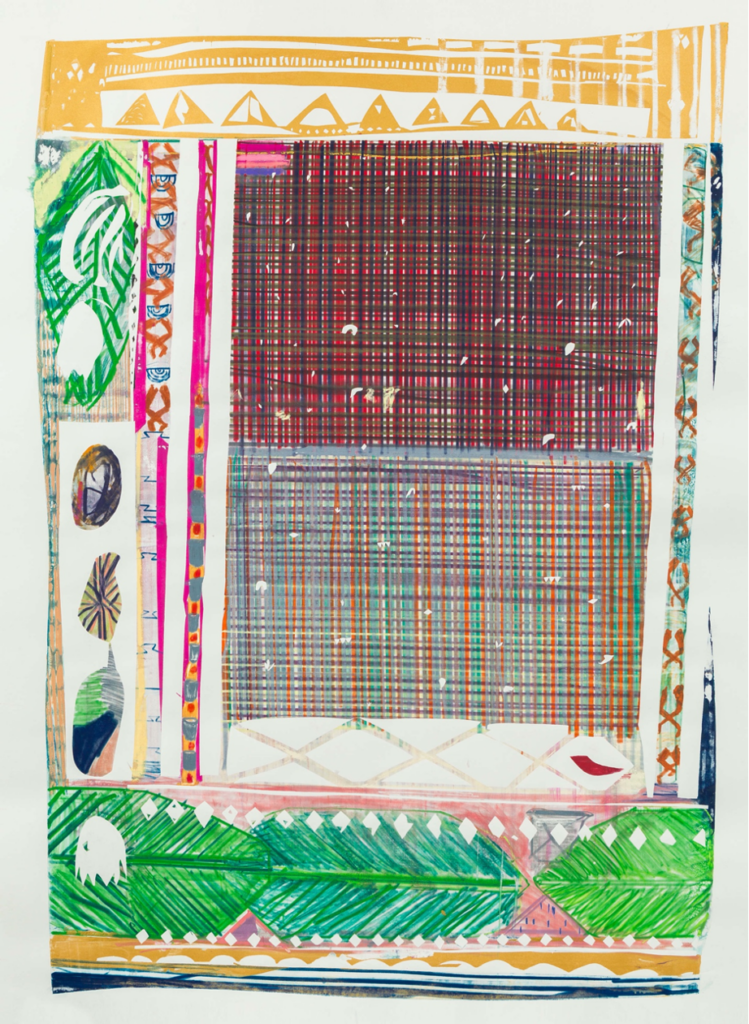

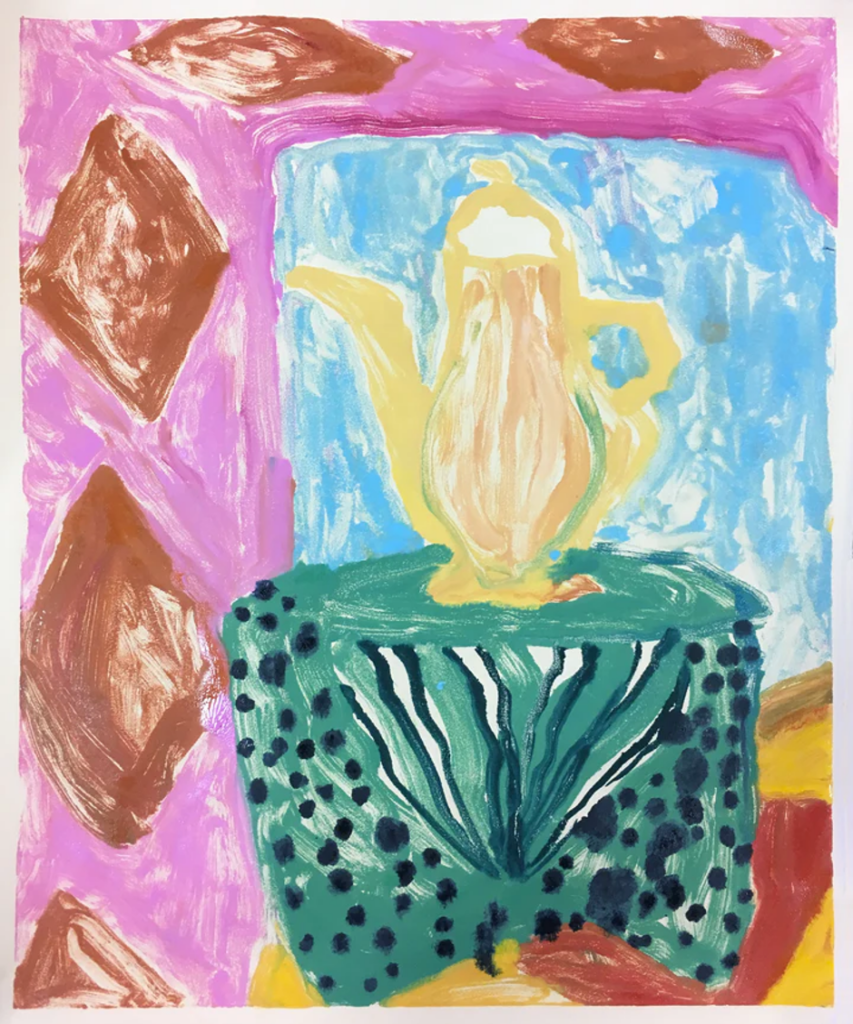

Padma Rajendran: Yes, of course! I started drawing in college. My aim was to be practical and apply my art knowledge and skills to a design career after school. After I graduated, I found that the elements of drawing––such as line, expression, and mark making––directly translated themselves to printmaking. And so, I started making a lot of watercolor monotypes in a community print shop setting in New York, at the Robert Blackburn Printmaking Workshop. Because I was making monotypes––which is very linked to drawing, taking a painterly approach, but is nonetheless categorized as printmaking––I thought at the time that it made sense for me to pursue a printmaking degree for my MFA. While I was in grad school at the Rhode Island School of Design, I was still making watercolor monotypes, but with silkscreen, and I learned a general approach to textile printing, such as how to print repeat patterns. My content shifted in grad school, from place and imaginary landscape to interiors––interior life, and the identifiers of home and location within interior spaces. It then made more sense for me to start using fabric instead of paper as the surface. I always thought of paper as being this kind of equalizer of mediums, as it’s a material that’s accessible to many people, but I think that’s even more the case with fabric. In terms of working outside of printmaking and fabric, I’ve always been interested in ceramics. But for me, ceramics has been a surface to support drawing. Now I take a more collage-like approach to this medium, rather than just drawing with glaze on the clay body.

B O D Y: Can you discuss your emotional and creative relationship to each medium? Especially to textiles, as that’s currently your primary medium.

Padma Rajendran: A big part of it for me is that everyone has a relationship with fabric–– it’s an accessible material. For people to connect to this medium, they don’t have to be academics or have a fine art background––we all occupy fabric, and so we all have a relationship to it. I think it’s easier for many people to approach fabric and engage with it without feeling like they lack the tools to read and understand it. People are able to connect to the narrative history of a piece of fabric or to the imagery on it. That’s a big factor for me. Additionally, and this may sound convenient, but I consider factors of storage and the ability to not be so precious with the material, the way I had to be with paper. There’s just different kinds of care involved in working with fabric compared to other materials that are considered more traditional fine art materials. I do think that because fabric is all around us there’s this immediate link to the body. I feel this especially when I make larger works, I do want the viewer to feel this kind of enveloping around them, that the work is there to be a soft supportive surface. Another aspect is that I find fabric just beautiful. There was a point where I found myself collecting fabric, and I think some people have that impulse to simply collect fabric without always fully knowing why. It’s a gesture that speaks to possibility. For me, it feels nice to engage with fabrics in a different way, especially in the beginning when I started working within this medium.

B O D Y: Do you find that fabric connects you to notions of family, home, and safety? This is something that I’m currently considering and exploring in my own textile practice.

Padma Rajendran: Yes, I think that the soft, enveloping space created with fabric conjures those very early childhood feelings of home. Being nestled in fabric provides such feelings of safety and comfort; it’s the physical comfort and the emblematic comfort, and that’s a major thing. There’s also just so much ritual surrounding fabric, which is an element that is deeply part of the work as well.

B O D Y: I’m curious about the fabrics of your childhood because I know that you were raised in different environments. How have these environments influenced you in terms of collecting textiles or being drawn to certain patterns and colors?

Padma Rajendran: Sari Series was my first entry into considering textiles. Even though that series of prints are on paper, it was the first time I considered fabric as part of the content of my work. These prints reference saris and their fabric structure, and these elements guide the narrative and symbolism of the works. Sari Series was also inspired by the performative element or the ritual of sari shopping, the physical gesture and the exchange between people that make up this process. In many South Asian households, saris are considered heirlooms, they’re passed down. Of course, there are varying degrees of usage for them, some are for daily wear, others for special occasions. The importance of saris between generations was something I wanted to acknowledge and give space to; I wanted this textile structure, the structure of the pallu, which is the loose end of the sari, to be an open space for talking about the past and home and family.

B O D Y: Let’s talk more about the themes of your work. I was really interested in what you said about story because I know that there’s so much going on in your works. Could you share with us the themes that have been central to your practice?

Padma Rajendran: I’m interested in the fabric itself, the conversations that surround it and its formal, emblematic, and symbolic qualities. I’m interested in the history of particular fabrics, their composition, their reference to pattern and regionalism, as well as the connotations that fabric conjures, and the uses of fabric as comfort keepers or identifiers of a person’s identity or location. The immigrant stories of women is another central theme; the contradictions inherent in society’s role and expectations of women and their inner lives and sexuality. I’m also interested in the contradictions within immigrant stories. I find that when I hear of people coming to the United States under such grueling conditions, there’s a lot of hope and optimism about coming here, but it’s far more complicated in terms of trying to forge that life here. Of course, things are easier here in the US, but there’s often disillusionment with what it actually takes to assemble a life here. It’s really complicated. So that’s also part of what I’m exploring, the relationship of contradictions that exist for women, and then also being an outsider here in the US, not just to form a life, but also that sense of belonging.

B O D Y: In our last conversation––and this has to do with your last point––we discussed ideas of home and homeland. And I remember you saying, “home is something lost.” That really stayed with me.

Padma Rajendran: I was thinking about the act of remembering previous homes, and the impact that each home we encounter has on us, and how our last home stays with us. Bachelard discusses those ideas in his book Poetics of Space, and I think that for many immigrants, home is even more complicated because the home in which you grow up, that you inhabit with your family, is often lost, impossible to access again. There’s an impossibility to recreate home for certain people, and home is then a place that becomes consistently evolving and redefined by location and people, actions, and time or experience. Even if you’ve moved from place to place, a person’s idea of home is often impacted by that first childhood home. As you move from one location to another, you always enter that space thinking about the last home you lived in. So, it takes time to think about re-establishing the sensation of home. I find myself thinking so much that home is only truly treasured once you’ve left it.

B O D Y: Having also immigrated as a child, I really relate to what you’re saying, to the impact of that first childhood home. Can you share with us where that first childhood home was for you? Just so the reader can contextualize a bit.

Padma Rajendran: Of course. I was born in Malaysia, and when I was an infant, I lived with my family in the UK. But for me, I would consider my childhood home to be Riyadh in Saudi Arabia. I lived there for six years until I was nearly eight, and even though we lived in different apartments and houses, the location and the life that was there––going to the same school with the same friends, those formative years––was in Riyadh. And when I moved to the US, when I was just shy of eight, that really shifted, because even at that young age, I acknowledged what it was to be cast as an outsider. I spoke English but with a different accent and dressed differently than my peers, which created a difficult transition to American life. So even though my immigration was comparatively easier than most, these formative years impacted how I consider and empathize with immigrant experiences.

B O D Y: My next question is about the relationship between materials and methods in your practice. You’ve already touched a bit on that

Padma Rajendran: Yes, the relationship with fabric is one that everyone has; most people can read this material, unlike oil on canvas or print on paper. That ability to access it is important. I’ve observed hesitations within my own family, and when I was a teaching artist, I noticed adults were often hesitant to read other objects. So that’s a big part for me in terms of working with fabric. I also think fabric and even ceramics are tied to this association to folk art objects. That too is part of this opportunity of access for certain groups of people. I’m curious about removing those barriers.

B O D Y: Is that regard for accessibility something you’ve always been attuned to or did that come later in your practice?

Padma Rajendran: That came later in my practice. After graduate school, I became more aware of this as I was working and teaching, and then also seeing my own family interact with my work. I do feel that I’m trying to bring out a certain visual language and visual references that are more accessible to a specific group of people. This may present limitations to what is usually considered the traditional fine art audience, but for the most part, I don’t think that’s the case.

B O D Y: Within the realm of textiles, you use multiple techniques. For example, watercolour monotypes, appliqué, and then in your new work, you’ve done this really interesting and beautiful felting. Can you discuss some of the different textile techniques that you use?

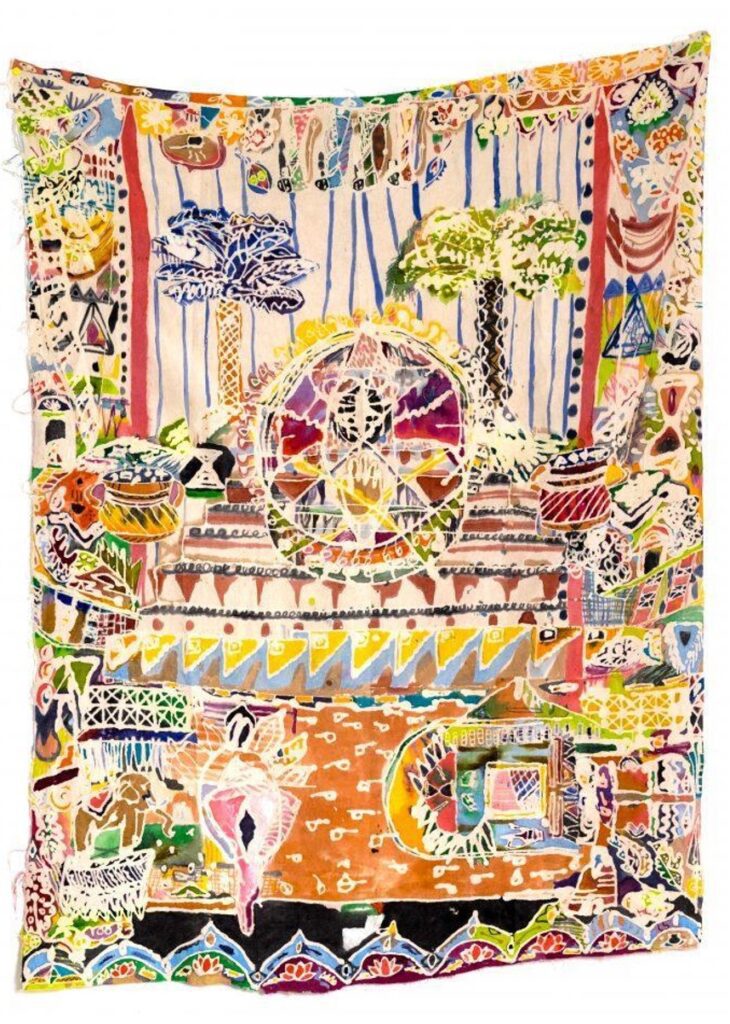

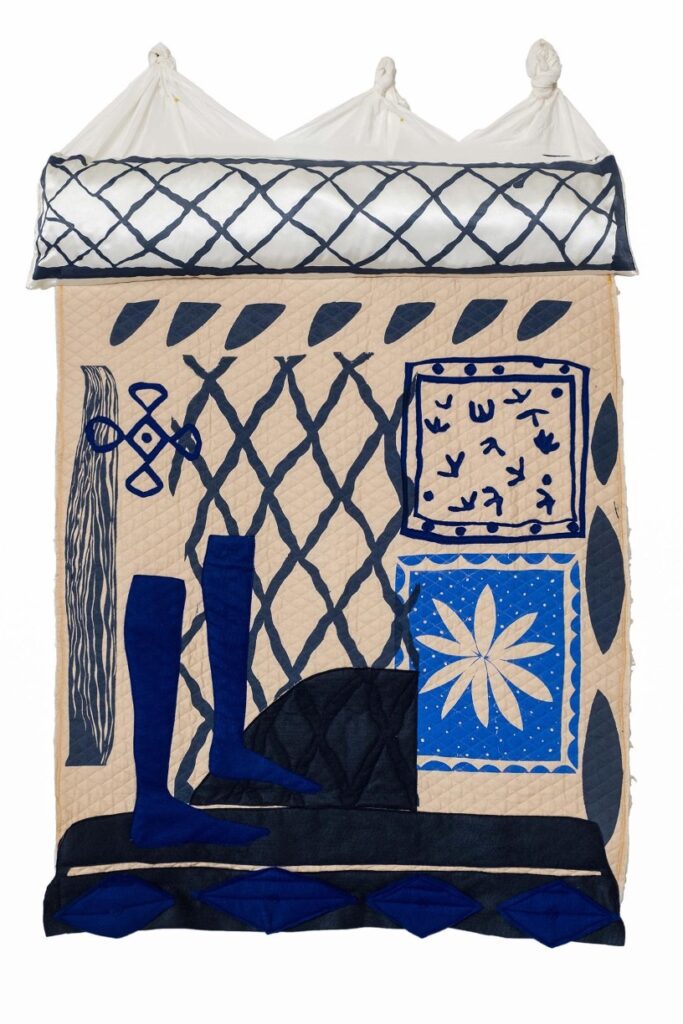

Padma Rajendran: Within printmaking on fabric, I’ve done watercolor monotypes, screen printing, some pochoir, which is stenciling, and I’ve used water-based resist and dye application directly on fabric. And then I’ve used appliqué. Sometimes I do use a combination of techniques, but most of the time, it’s just one technique at a time per work. I think about different ways in which the image can develop, perhaps I want to imply a certain hierarchy of information or I’m considering how depth can factor in. Most of the time I like the way there’s flatness occurring within the work. When I structure certain pieces, I think about the stacking of information visually; when a piece of information is on top of another, rather than there being a foreground, middle ground, and background. For example, in certain South Asian miniatures, the way pattern remains flat, the illusion of perspective or deep space is created by the perspectival line itself. My interest in the use of resist is this link to batik, which my mum collected and that I also grew up seeing in Malaysia. So, for me, that’s the link to location. Then the acts of working with fabric, setting dye, and ironing and washing fabric pieces is linked to domestic labor.

B O D Y: Your thoughts on composition segue nicely into discussing visual language. You have a very rich and distinct visual language, and there’s a lot going on in each of your works. Can you walk us through some of your reoccurring motifs?

Padma Rajendran: A reoccurring motif is the palm tree, which for me references home and the homeland, the othered place that one might always be looking back to. And I use a lot of mango or paisley motifs, which are signifiers of fruit, fertility, ritual. The paisley is a textile pattern, so it refers to that theme of regional motifs that are found in a lot of South Asian textiles. The paisley motif also speaks to the history of British imperialism in South Asia; colonialism is always there. And then there’s flowers, referencing fertility, beauty, water; the pitcher, vessel, and the spoon, again speaking to fertility and life of the female body. So, there’s a lot of fertility, which I think of as blessing and burden. And mountains: fertile place, land of opportunity, which are also signifiers of the West, of the Americas, of this potential of place. In the composition of the works, there are “pockets,” these areas of space and time that are often separate, but they’re part of the overall story. That refers to this idea of epics, which I’m really fascinated by. These very particular Asian stories that span many generations and are usually about the lives of women and intergenerational struggles.

B O D Y: Have these epic stories always resonated with you?

Padma Rajendran: As a kid I remember watching films; they were on TV, and they were what my mom was watching. Nineties films like The Joy Luck Club, or even American sagas, chronicling American history, but that didn’t entirely feature white people. There was something in these stories that I connected with, that I enjoyed. Of course, as a child, you’re just watching something because it’s there, because your parents are watching. But those films are recollections from a part of my childhood, and I sometimes go searching for them now.

B O D Y: Is there a specific work or body of work that you created that more explicitly deals with that intergenerational epic? Or is that reference present in the background of all your work?

Padma Rajendran: For some works it’s present in the background. I would say in Sari Series it’s linked to personal experience, where I’m structuring these ideas of home in the past, against this practice of the present, or even future, this realm of the imagination. I think Close to Wishing or Lemon Life have these distinctive glimpses into what people are searching for––and I say people, but there are only body fragments, it’s always a hand or a gesture reaching out or perhaps even feet that indicate place. But it’s often more obscured, part of the making process.

B O D Y: Hands––also the forearm––and feet are a big part of your visual language. They are reoccurring motifs in your work and seem to indicate the theme of place.

Padma Rajendran: Yes, place in terms of what that person is reaching for. And most often, the hands have a distinctive color to them. And that’s something that I always want to be evident and clear, that connection to brownness, to dark skin.

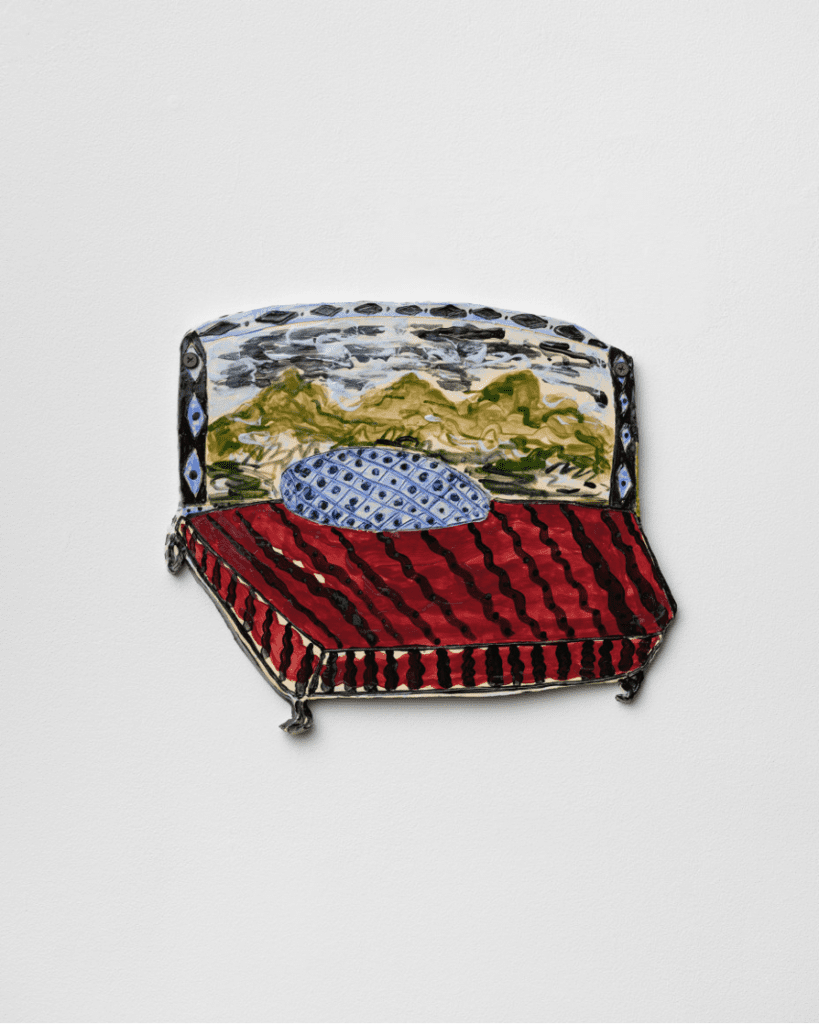

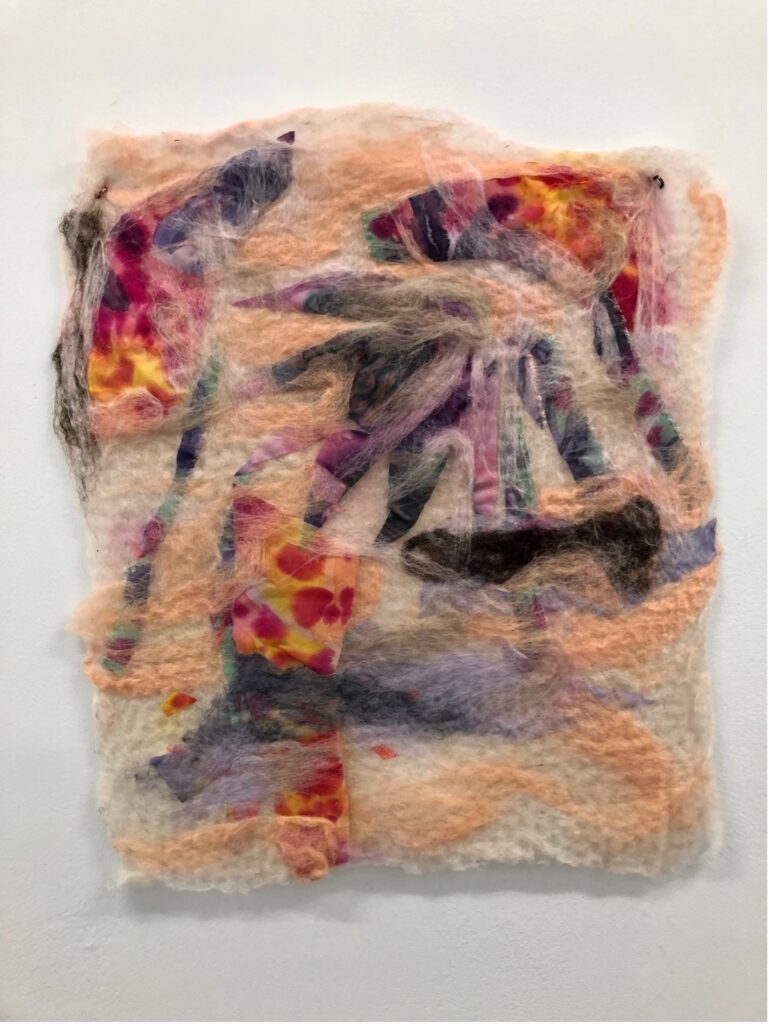

B O D Y: Let’s discuss your present practice. In the fall of 2022, you had a three-person exhibition at the Hudson House, in New York State. I was really intrigued by your new felted works––I don’t think that you’ve done felting before, right? I love these felted works, they’re really different from what I’ve seen in felting.

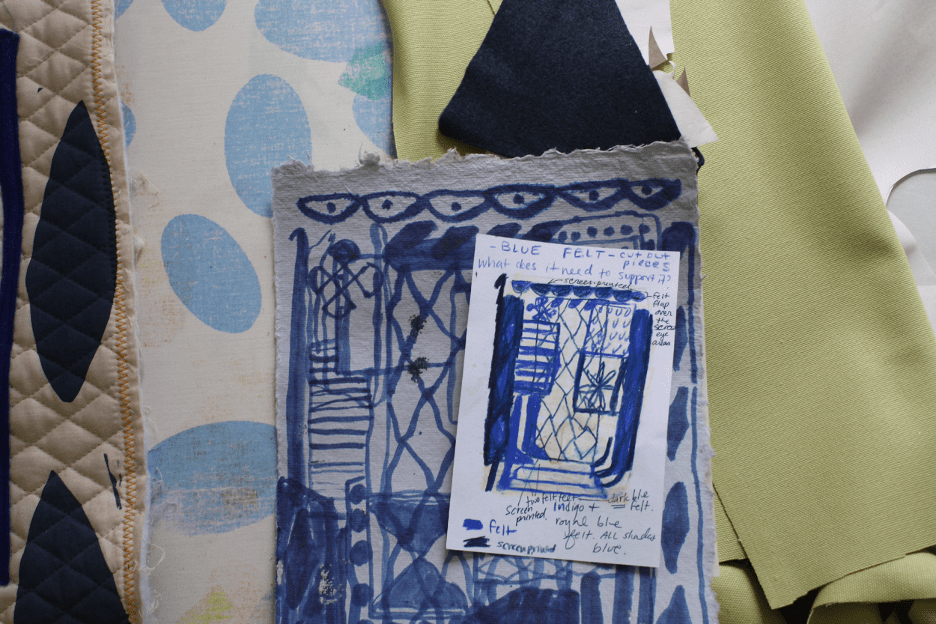

Padma Rajendran: Thank you! Those felted works came about because the organization River Valley Arts Collective provided me with a money and materials grant and the opportunity to work with a material––wool––that I had never worked with before. It took me a moment to understand what I was going to do. At first I was going to treat the wool like a placeholder for something I already do, such as for some stuffed pieces––I was going to just insert the wool in a certain way and dye it. But I decided to try felting, and it was great because I treated it like drawing. I thought about collage and fused it with some of the silk pieces that I had dyed; some of which I had set the color. And there’s this kind of watercolor moment happening with the effect of the dye and the wool, and that was really exciting to me. You had asked earlier about my approach to fabric, ceramic, sewing, appliqué, and felting. I do find that I don’t do things the technical or “right” way. And that’s just part of the exploratory process, which is really fun for me. I also consider my approach part of my “hand”, that the work is going to look like mine regardless of the material that I’m using, because I’ve made it, and it is of me. So, with the new felted works, it was fascinating and fun to create new structures with wool, but also with other materials and processes––in this case silks and dyes––that I’ve used in other works. Because I was working with this new material, it made me feel like the stakes were lower, even though I knew they’d be exhibited. It just didn’t have the baggage of previous works or previous ideas or expectations. And so that show and that work has really prompted me to do more with wool, such as working in a larger scale and incorporating different fabrics.

B O D Y: That’s another reason why I’m drawn to your work–– it doesn’t feel technically rigid, and your hand really comes through. I’m wondering how that relates back to printmaking, because in printmaking there’s that tradition of doing multiple editions and this requires a level of skill and perfectionism. Is that tradition something you pursued in printmaking, or did you go in a different direction?

Padma Rajendran: I definitely went in a different direction. I’ve made a few editions, but when I’ve made the print or the plate––the matrix for the prints––it was in a non-traditional way. Ultimately, I’m not interested in editions. I don’t love to make them! And when I have, they’ve always been fairly small editions, maybe 25 to 30 prints. In the past, I’ve screen-printed or block-printed small cards for people, and I don’t necessarily consider this part of a print edition. I take a lot more pleasure in printing those, because I’ll print about 100, and even on that scale there’s not too many layers to consider, and they have this very intentional purpose. I know when I’m making something, this kind of specific gesture, ultimately, the work is not about the printed edition, it’s about the gesture to someone else. And I think that in terms of the physical work in textiles or the lunch project that I’ve done, it’s about this connection to others. And how that can potentially be nourishing or a kind of offering.

B O D Y: Can you tell us a bit about the lunch project?

Padma Rajendran: I started the lunch project in 2014. I provided a homemade lunch to someone I didn’t know very well. I would drop the lunch off and ask them to eat the meal alone and participate in the project by filling out provided prompts. This project was an attempt to record the labor involved in a domestic task––connecting the cooking process in the kitchen to the art making process in the studio and embracing the concept of gift or offering, and how this is so commonly carried out across the globe through food.

B O D Y: Do you consider the lunch project relational aesthetics?

Padma Rajendran: Yes, when I started that project, I was thinking about that! Of course, there’s been a history of artists working with food and really considering relational aesthetics, but because it’s been a few years since I’ve done a lunch project, it feels really distant––my last one was in 2019, then the pandemic put a stop to them. So, I feel a little distant from speaking about it now versus the ideas that I had formed around it when I was doing the project.

B O D Y: What’s next for you?

Padma Rajendran: I definitely plan to continue the felted wool pieces and to let them be a little more complicated. They’re guided by drawings, and so they can have more elements within them. And I would like to get back to ceramics, it’s been almost a year since I’ve worked in that medium. There’s a lot of tending to in clay––you’ve got to be around for the material. Also, I’m preparing for a two-person show in the summer of 2023. I want to create new work for that show because the past year has been really occupied with caring for my daughter and the life transition to motherhood. So, I feel really excited and ready to get back to the studio. And I think that parenthood has also brought about different ideas and expectations of what’s happening visually and how the work should function. These days, I consider how I want to feel or what I need from the encounter with an art object or art experience. I also find myself considering the elements of connection to storytelling a little differently. It is harder for me to be in the studio and my energy level is different for the moment, but I have a different kind of focus when there.

B O D Y: Going back to your felted works, I was thinking about wool as a local and regional material. Does that material tie you to your home in Catskill, New York State, the region that you now inhabit?

Padma Rajendran: Yes, the wool that I received for my grant is a regional material, which is a very raw wool that has a lot of plant matter in it. I incorporated this wool with merino wool that is a bit more refined and has been dyed. For me, the connection and conversation between these different categories of wool coming together is meaningful. The process of communication between materials happens a lot when I structure my fabric pieces, for example when I combine different silks together in a work or different cottons. I also consider the implications of different surface treatments, how the materials are lending themselves to part of the surface, that drawing aspect, and how things are resting within and on that structure.

B O D Y: Can you discuss your process of combining textiles?

Padma Rajendran: For some of the fabric pieces, I’ll create the structure first before drawing or piecing the parts together. I use a combination of different silks, sometimes you can really see the seams of the multiple pieces. Often things look a little wonky. I really love that because it reminds me not just of collage, but references how a surface is established by the sum of its parts. I have an admiration for and feel a connection to quilters: they’re making images, making paintings, from all these different fabrics. I’m not doing anything close to that, but I do think a lot about how quilt-making involves piecing parts together––be it materially or narratively––which I do in my own process, even though this may not come across.

B O D Y: I think this relationship to quilt making really comes across in your work. You’ve mentioned collage and assemblage, and I’m wondering if you could speak to what that means to you and what you’re drawn to in those practices?

Padma Rajendran: In collage––and I think that’s also why I like silk screening––there’s this sharpness in the form, that cut line is really distinctive and declarative. With pochoir (stenciling) this occurs too. And it all comes from cutting. For me when I silkscreen, I love making rubylith stencils. I just love how this process functions graphically. I’m also curious about how layers emerge within that. I think about if there’s a hierarchy happening in terms of the information that’s being laid down and the story that’s emerging because of this process.

B O D Y: Do you carefully design the works beforehand? Or, for example, in your appliqué works do you just piece fabric together without drawing the whole work out?

Padma Rajendran: I do draw things out, and when I do make the appliqué pieces, I still do that. I draw things out multiple times. Once I decide on a design, I will cut things out, and then still play with the different pieces when they’re on the surface structure. But I do find that things move faster when I’m doing a lot of drawing and considerations of the piece beforehand. I do love just kind of going into it without planning, but I don’t do that very often, as the process is a lot slower if I don’t have a roadmap. I even draw the dye pieces out, even though they change a lot, as I’ll create around five or ten drawings of the same thing while I’m making them; this sketching out process is just faster and sometimes I have deadlines to meet.

B O D Y: That makes sense as drawing is your first medium. I came to drawing through creating textiles, and I rarely draw out any of my works beforehand, so I find your process really interesting! Let’s move on to the final question, which is about colonialism. As a Tamil person and member of the South Asian diaspora, how do you unpack that history of colonialism in your work? Is it a consideration for you?

Padma Rajendran: Colonialism enters my work through object, pattern, and food. I reference our reliance and histories though the inclusion of (Cavendish) banana, paisley, and the intentional assertion of dark skin and gesture. I consider my own part of being of somewhere else, of traveling, and how I view land and its generation of occupants. Colonialism has impacted so many reasons why we are not in certain places despite being from there and occupying the identity markers on our bodies that signify our belonging to other places. The work very much comes from this place of wanting to have connection to where I’m from, but also acknowledges that I’m not fully from there either. The work also makes a point of making visible stories connected to being South Asian that don’t necessarily get considered in North American mass culture. I find myself wanting to showcase these stories and to reclaim and explore certain narratives, because I often feel like the ones that are told are not the ones that I feel connected to. Some of that has to do with the aftereffects of colonialism, for example, how race and colourism are considered within our own culture as well as the model minority myth. I’m also incredibly fascinated with the paintings and objects that were looted from India. As artists or academics those are the objects that we can easily access. But it’s really complicated to engage with them; to consider how I engage with them, and what kind of reference I want them to have in my work. Something that I’ve been thinking about a lot is the fact that I’m learning about my own culture through the lens of the oppressor. And of course, my learning has also been pieced together by my personal experience and memories of going to India––even though I haven’t been there in a few years. Sometimes considering one’s culture is really rooted in family relationships, and I think it’s common for people to search for an understanding that goes beyond those relationships. Much of the cultural art objects seen around the world away from their original homes are through collections and often came to view by looting. There’s a force, a violence and hidden stories behind these objects. Textiles have a systemic history of appropriation. I have always been fascinated by this and haven’t yet fully researched all the layers of this specific global relationship.

B O D Y: For example, people don’t often know that the madras print and the paisley print were appropriated. When my father read my research paper on Sari Series, he found it really interesting to hear about the origins of these prints, because he didn’t know any of that history.

Padma Rajendran: It’s fascinating because it doesn’t occur to us that the paisley print is a South Asian print, because the British named the print after the town in Scotland called Paisley, where the print was later manufactured. I think it’s really interesting that there’s an assigned name to that print, which is independent of our culture.

B O D Y: In a previous conversation, we discussed the influence of bell hooks’ book Art on My Mind. Can you share how this book impacted you?

Padma Rajendran: I first fell in love with that text because of the essay “Women Artists: The Creative Process.” I felt an immediate connection to the message of the text; it allowed me to really understand myself and what I needed to become a successful visual artist and to make my work; bell hooks is so declarative about that. I appreciate how she asks questions, that’s part of her process, part of her stance. And it gave me permission in my own writing and work to simply ask questions, to not feel that I needed to always have the answers; the work isn’t always the answer, the work is the question. That feels really good. I hadn’t read that essay in a few years, and I read it earlier before our conversation; it’s short, but still feels very much in line with what I’m thinking about now and with the issues that are occurring now, even though the essay was written some time ago.

B O D Y: I feel the book was so ahead of its time. I read it for the first time a couple of weeks ago on your recommendation. That essay also really spoke to me. How old were you when you read it? Was it at the beginning of your journey as an artist?

Padma Rajendran: I read it in graduate school. It was after I had completed a semester or maybe a year. But I remember reading it in the winter and just immediately feeling at home. The way hooks writes, the way she brings up these ideas, even though she’s talking about the Black experience, I found myself connecting to a lot of the content and questions that she posed. That entire book just authenticated so much of my own process and the way that I think. At the time, I felt like perhaps my ideas were too simple, especially in an academic setting. While there I didn’t hear from many diverse voices. A lot of my peers and faculty members didn’t share my background and experiences. In graduate school, there’s just this idea of what feels like graduate-level conversations, like this idea of food, it didn’t necessarily always feel like worthy of investigation within that context. It felt too simple, and I wondered if my ideas were too sweet or homey. But they’re coming from a much deeper place. So, reading hooks played such a large part in me thinking, “Oh, my perspective and ideas are valid, something real, even if only a couple people are seeing it, it exists, and it’s important to talk about.”

About the Interviewer:

Antoinette Karuna (she/her) (b. London, England, 1981) is a visual artist working primarily in textiles and film. Her work has been shown nationally and internationally, including at the Toronto Intl Film Festival, Vancouver Intl Film Festival, Bucheon Intl Fantastic Film Festival, the Khyber Centre for the Arts, and the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia. Her projects have received funding from the Canada Council for the Arts, the National Film Board of Canada, and Arts Nova Scotia, among others. Karuna holds a BA in Communication Studies and Creative Writing from Concordia University, Montreal. She is currently enrolled in an MFA in Visual Arts at Memorial University, Newfoundland and Labrador. There she is undertaking a creative inquiry into the complexities of mixed-race identity with the assistance of a Canada Graduate Scholarship – Master’s grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC). Karuna is Sri Lankan Tamil through her father and French Canadian through her mother. She spent her childhood in London, England, then later a decade each in Montreal and Berlin. She teaches Filmmaking at St. Francis Xavier University and resides in Antigonish, Nova Scotia, Canada.

Visit antoinettekaruna.com or follow her on Instagram to learn more.