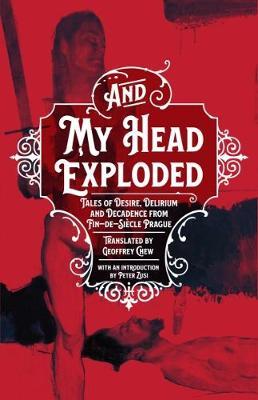

And My Head Exploded

Selected and translated by Geoffrey Chew

Jantar Publishing

2018, 200 pp

And My Head Exploded: Tales of Desire, Delirium and Decadence from Fin-de-siècle Prague, a new collection of short stories translated by Geoffrey Chew, is an extremely welcome addition to the corpus of Czech literature in English. While these stories are no longer as shocking as when they first appeared, they will likely surprise readers who might be familiar with Czech literature for a very different range of subjects and themes. This is due in large part to the paucity of translations of late 19th and early 20th century prose in the repertoire to date. These stories also shatter the widespread conception that prior to the 20th century Czechs were concerned with developing their own national literature and did not look to Europe for inspiration.

In his introduction to the book, American scholar Peter Zusi mentions the tendency to see “smaller” literary traditions in isolation, pointing out that they are gradually deformed by the choices of translators, publishers, and even readers. Jaroslav Hašek’s Adventures of the Good Soldier Švejk (1921–23), for instance, has long been the most famous Czech novel. As a result, authors writing in the tradition of Hašek’s beerhall banter, such as Bohumil Hrabal, may be likely chosen for translation. Readers have also been interested in dissident literature from the Communist period (1948–1989), and publishers have found it lucrative to meet that demand. The emphasis on translating these two kinds if writing has led many foreign readers to believe that Czech literature is generally realist and often humorously subversive. Zusi underlines the importance of And My Head Exploded in broadening this view.

One of the collection’s most significant aspects is its remarkable range. It includes stories published between 1892 and 1917, but, even more notably, their authors were born between 1841 and 1884 (an impressive range of 43 years). Julius Zeyer, for example, was known to the Czech Decadents as a member of the older generation. His work, which is representative of what I call Decadent Romanticism, evinces the nationalism typical of his generation, but it is a kind of mournful or even despairing nationalism.

It is no coincidence that the first story in the collection, Zeyer’s “Inultus: A Prague Legend” is set twenty years after the Battle of White Mountain, a devastating defeat for the Czech nobility that led to the Counter-Reformation and the consolidation of Habsburg power. Zeyer’s characterization of the Czech Lands influenced the Czech Decadents, especially Jiří Karásek, also included in the anthology, whose own portrayal of Prague as a dead city culminates in his novel A Gothic Soul (1900). The trope of the “dead city” is typical of Decadence throughout Europe, brilliantly culminating in Thomas Mann’s classic novella Death in Venice (1912).

Zeyer’s story highlights additional themes that migrated from Romanticism to Decadence, including “dying into art,” a trope beloved by writers of a certain bent from Edgar Allan Poe to Rachilde. However, what is typically Czech is that Zeyer makes this theme thoroughly Catholic – which is somewhat ironic, considering that most of the Czech nobility before the Battle of White Mountain was Protestant. Yet European Decadence is closely tied to Catholicism, with its aestheticism and mystery: Joris-Karl Huysmans, author of the “Decadent breviary” Against Nature, thematized Catholicism increasingly in his oeuvre.

Two other themes that are downright cliché in both Zeyer’s strain of European Romanticism and in European Decadence are “the apotheosis of art” and the femme fatale. These motifs reappear in Miloš Marten’s “Cortigiana,” which adds yet another major trope to this inventory – “the orgy before the collapse.” Marten features a femme fatale who plans to kill all of the celebrants at a luxurious party in the midst of plague-ridden Florence with her poisoned kisses, as she herself is infected with the plague. In Arthur Breisky’s “Prose Poem,” another story from this anthology, it is a man who consciously spreads syphilis, until he kills himself. This story bears an obvious resemblance to Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890), insofar as Dorian spreads corruption until his own self-destruction.

On a different note, I am heartened to see a woman, Božena Benešová, included in Chew’s anthology. A Decadent gloom permeates her stories, which are less hyperbolical and more intimate than the other stories in the book. “In the Twilight” may be read as a feminist critique of patriarchal society, especially marriage, reminiscent of Henryk Ibsen’s ground-breaking drama A Doll’s House (1879).

In short, this anthology broadens English-speakers’ perception of Czech culture by bringing new authors into the canon, and it clearly shows that, even in the 19th century, Czech literature was not simply a reflection of the Czechs’ search for a national identity. This volume makes it clear that Czech writers were familiar with major European authors, and that their work should be considered an integral part of European culture.

— Kirsten Lodge

_______________________________________________________________________

KIRSTEN LODGE is Associate Professor of English and Humanities and the Humanities Program Coordinator at Midwestern State University in northern Texas. She holds a Ph.D. in Russian and Czech Language and Literature from Columbia University, and she lived in the Czech Republic for seven years. Her recent translations include Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Notes from the Underground (Broadview Press, 2014), Jiří Karásek’s A Gothic Soul (Twisted Spoon Press, 2015), Leo Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilyich and Other Stories (Broadview Press, 2017), and Evgeny Zamyatin’s We (Broadview Press, forthcoming in January 2010). She is currently working on a new edition of Leonid Andreyev’s The Red Laugh for Broadview Press.

_________________________________________________________________

Read more by Kirsten Lodge:

Translations of three poems by Štěpán Nosek in B O D Y