Rachelle Dang (b. Honolulu, HI) has exhibited her work in New York at Fergus McCaffrey, Nathalie Karg Gallery, Motel, Hunter College, Cooper Union, and SPRING/BREAK Art Show; and in Hawaii at the Honolulu Museum of Art and Hawaii Pacific University. Other exhibitions include the Haverford College Art Galleries in Philadelphia and the Korean Cultural Center and Gallery 825 in Los Angeles. Upcoming exhibitions in New York include the Socrates Sculpture Park Annual (2019), and solo presentations at mhPROJECT (2019) and A.I.R. Gallery (2020). Dang has been an artist-in-residence at the Studios at MASS MoCA, Shandaken: Storm King Art Center, Cooper Union, Vermont Studio Center, and Sculpture Space where she received an Emerging Sculptor Fellowship. She was awarded a 2019 Emerging Artist Fellowship with Socrates Sculpture Park, a 2019-2020 Fellowship with A.I.R. Gallery, and a 2019-2020 residency with the Smack Mellon Artist Studio Program. She was recently nominated for the Dedalus MFA Fellowship and the Rema Hort Mann Emerging Artist Grant. Dang received an MFA from Hunter College and a BA from Wellesley College.

I met Rachelle Dang while pursuing an MFA at Hunter College in NYC. Seeing her work develop over the course of her degree acquainted me with her remarkable thought process in parsing the biographical details of her life with the colonialist history of her home state, Hawaii, and the surrounding regions. The following interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. – Jessica Mensch

B O D Y: Your recent work explores your own history – specifically the ecological legacy of colonialism in Hawaii and the Pacific Islands. At what one point did you decide this was something you wanted to confront in your work? I’m asking because you were making abstract paintings just a few years ago.

Rachelle Dang: It seems strange to say I began this work when I was 19, but the journey of realizing these ideas in visual and material ways has been quite long. In a college printmaking class I made two works about the Pacific that perhaps anticipated the recent project: one was about sugar plantations and tourism, the other fused imagery from Gauguin with nuclear test images. I had a lot to figure out: where I was from, what that history was about, what kind of artwork I wanted to make. I was influenced by faculty members at Wellesley College who were engaged with dialogues about colonialism, and by artists at the college whose works were political and conceptual. Adrian Piper was teaching there at the time – that was huge for me. I had a very standard, Americanized education in Hawaii. I didn’t know how to recognize or understand the ways colonialism connected Hawaii to the rest of the world. And I didn’t know about contemporary art and all it could encompass. After college and a long absence from art, I began painting with much of the same content in mind, but it was hidden under formal investigations into pattern, color, gesture.

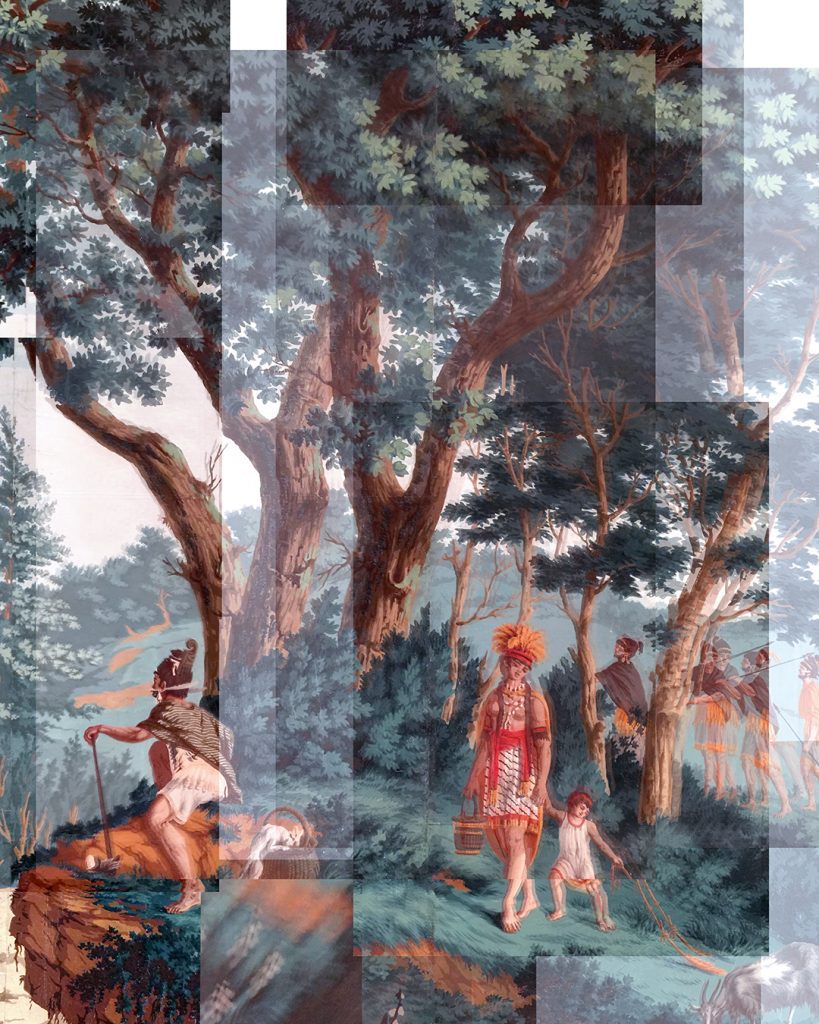

B O D Y: Ok, so it was during your MFA that you transitioned to sculpting and returned to an arena of thinking that was more overtly political. There’s a real tension in your work between beauty and the abject. I’m thinking of your recent show, Southern Oceans, at Motel in Brooklyn, NY. Here, the subtle color of your ceramic glazes, your treatment of the copper botanical cages and your soft focus, low saturation reproductions of panels from the 18th century French neoclassical panoramic wallpaper, Les Sauvages de la Mer Pacifique, work to create an alluring and sensorial experience. Yet upon closer inspection the same jewel-like ceramics that are cast from breadfruits reveal tearing and disfigurement at their edges. Even the panorama, collaged together from low-resolution phone photos, betrays the assumption of visual continuity that is the hallmark of the panorama. And the image the panorama itself depicts, one learns, is a testament to the brutal colonialist history of the islands.

Rachelle Dang: It helped a lot to engage with this difficult content in a material way. The work began through my initial encounter with the wallpaper at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and by working with ceramics. Handling clay opened up ways for me to comment critically on the wallpaper and the projects of empire, while relating to the natural world: ecological cycles, environmental devastation, vulnerability. I did things with my hands in shaping the cast clay breadfruits that were disruptive, that conveyed rot. Bringing in sculptural forms such as the copper-covered plant transport carrier, along with the 250 ceramic breadfruits, contributed to an immersive space that was seductive and yet disturbing. The viewer is immersed, there is a lot to look at, and lingering there invites introspection. The paradox of the beauty and violence, the fragility and the rupture, the seductive and the uncomfortable, makes it possible to have an active viewer – someone who would stay to question, wonder, reflect, scrutinize.

B O D Y: The closeness with which your sculptures relate to their referent, the cast ceramic breadfruit for example, evoke the logic of a found object. Yet, how you engage with their referent via the materials you use and the manner in which you use them all work to mythologize the referent. This results in a shift or expansion in the viewer’s perception. Where would you say you stand in relation to the referent object?

Rachelle Dang: Studying with Nari Ward at Hunter had an incredible impact on me. At the time I began studying with Nari, I was creating installation work from found items placed alongside each other and arranged in a room environment. He told me two things that just startled me: transform the found objects, and go theatrical – go for drama. I spent the next four semesters trying to figure that out. Collage and appropriation are important for me, but with the current work I use the referent as a starting point – remaking, reconstructing, and rebuilding differently. Whether it is the wallpaper, the breadfruits, or the 18th century botanical shipping carriers, recreating these objects is my way to examine this history and make it more relevant, more complex, more timely. It is how I bring this history back into our moment and our physical space. And to have some authority and creative power over this history and what these objects represent.

B O D Y: You are participating in a fellowship and exhibition at Socrates Sculpture Park in Queens, NY, this fall, and you’re also an upcoming artist fellow with A.I.R. Gallery in Dumbo, Brooklyn. What sort of ideas are you floating for your next series of works?

Rachelle Dang: I am trying a major shift in scale for my outdoor work at the Socrates Sculpture Park Annual this October. I will have a giant, outsized seed box with an open lid modeled after 18th century boxes for transatlantic seed exchange. The work is titled “Seed Box: Trees of New York” and will contain six living trees along with large hand built concrete sculptures modeled after a winged seed, chestnut, and pinecone. The work relates to enlightenment-era science and ecological systems that have been connected through economic interest, colonial trade routes, and global commerce. And I love artist boxes too, such as those by Joseph Cornell. The work at Socrates will have an educational dimension to it, in addition to being a wonderful living sculpture that relates to the natural world. With my other work I’m trying to get at something more psychological. Roberta Smith wrote about Louise Bourgeois that her work demonstrates “with a special force that the child is mother to the woman, as well as to the artist.” I want to see how my engagement with botany and colonial history can merge in my work with the domestic space and the space of childhood.

Further Reading:

To see more of Rachelle Dang’s work go to her website at: http://www.rachelledang.com/