_______________________________________________________________________

US poet Francesca Bell recently interviewed German poet Max Sessner for B O D Y about his work, some of his thoughts on poetry and his upcoming book of poems, Das Wasser von Gestern.

_______________________________________________________________________

FRANCESCA BELL: I’m very curious to hear how you became a poet. At what age did you become interested in poetry, and how did that come about? Do you remember the moment when it occurred to you that you might become a poet yourself?

MAX SESSNER: In the house of my parents, there was not a single book with poems in it. I still remember that I wrote my first poem at the small public pool of our village. I was so proud that I read it to the swimming pool attendant. What this poem put forth, that I don’t know anymore. Sometimes, my grandmother cut out poems for me from her old ladies’ magazine. Possibly, one of these was the trigger, and my grandmother made me into a poet. That first poem, sadly, like almost all of the poems that I wrote up until the mid-80’s, is lost.

FB: You, like me, are unusual in that you are a published poet without a formal education and with no connection to the academic world. Like me, you do not teach writing or literature and have, rather, worked at a variety of unrelated jobs. What effect do you think this has had on your writing and on the reception your writing has received? Do you see advantages or disadvantages to this or both?

MS: Probably, I never would have studied literature anyway. More likely history or art history. I don’t know therefore if a formal education would have given my writing a different direction. There are many poets who keep themselves above water with all possible jobs. I have always liked that. One is then a little bit more firmly tied to everyday life. I never wanted to be a “freelance author.”

FB: I have by now translated almost fifty of your poems. I remain fascinated and flabbergasted by how you are able to write poems that are very surreal but that can be experienced as so, well, as so real. Can you talk a little about the role and purpose of surrealism in your work? And also about how you feel you achieve the effect of realism and surrealism at the same time?

MS: I always imagine that the objects that surround us daily lead a life of their own. Very philosophical, very tolerant. That they would like to understand us exactly as we would like to understand them. My manner of seeing results possibly from this desire to understand, the manner of not pulling the gaze too quickly back, of expanding the gaze; then, with some luck, things find their ways to each other that otherwise wouldn’t have managed it. One can call it surrealism or also just a slight displacement of reality.

FB: I marvel at the way you use time in your work. One has, reading your poems, the sense that a person lives their past, present, and future all at once. Can you speak about time in your poetry, as subject and device?

MS: Perhaps poems are something like clocks that stand still. While the time outside continues, they always display the time of their origin. That has something comforting in it, and, like thoughts or memories, poems are bound to no chronological sequence of time. One poem can then, I think, combine different times within it, and be situated, so to say, at a safe distance from successive time.

FB: Before finding you, I searched for a few years for a contemporary German poet whose work I wanted to immerse myself in. I read literary journals, the anthology JAHRBUCH DER LYRIK, and I also looked around online. I found a great number of poets writing in what seemed to me to be a very vague, abstract sort of style. It’s a style I am not very drawn to, frankly, and it is a style that I despaired of being able to translate well. Could you talk a bit about the current state of German poetry? What is popular, and why do you think that it is?

MS: To be honest, I don’t concern myself all that much with the actual German poetry scene. Trends and styles don’t especially interest me. There has never been more poetry. I don’t want to and cannot anyway keep up with it all. What is popular this year disappears under the oven by next year. It is all very suspect to me. The distribution of the prizes comes very close to relying completely on an often very one-sided literary criticism. I am friends with several poets; that is already my entire contact with contemporary poetry in Germany.

FB: Who are some of your favorite poets writing in German, from any era?

MS: Every poet whose poems I carry around with me longer than four weeks is actually a favorite poet. That goes for all eras. At this time, I am reading the poems of Andreas Altman, a poet of my generation, whom I find unbelievably good. But to name a few old ones: Claudius, Eichendorff (the Romantics in general), Theodor Kramer, Brecht. It could also be though that I simply have favorite poems more than actual favorite poets.

FB: You have a new book coming out soon, Das Wasser von Gestern (edition AZUR, 2019). I read that you feel your style in this new book has changed, has become closer to prose than in your previous work. Is this an intentional change? If not, how do you think it has come about?

MS: My poems had all along a certain amount of prose. There is definitely a narrative structure in them. This isn’t very common in German poetry. Why this amount has suddenly now become more was not a conscious decision. In the course of time, the imagery has reduced itself without the poems thereby really missing something. They are, though, as before, contingent on rhythm and structure, poems and not poetic prose.

FB: You’ve written many ekphrastic poems. Is this a conscious decision, or is it just something that happens? I know one writer, for instance, who keeps a basket of postcards on her desk in order to have inspiration waiting there. Do you keep art on hand to write from?

MS: It is always a conscious decision to write a poem based on a painting or a photograph. If one so wishes, it is a sort of resumption of the painting in the poem, a bringing of the painting into writing, not a describing. With some luck, a totally distinctive version of the master clicks for me, and the poem functions on its own. That doesn’t always work, some pictures simply insist too greatly on their sovereignty.

FB: Can you tell me a little about your process and your writing habits? For instance, do you keep to a schedule or write when you feel like it? Do you revise a little or a lot or not at all?

MS: No, I don’t have a schedule. It all happens rather randomly. On the way to work, a scrap of a sentence from someone walking in front of me, a glimpse of something. These small things, strewn in the day, that demand attention. Then I carry this around weeks- or months-long within me. As a note or in my head. The whole thing has something to it that resembles a very cryptic shopping list.

Hard to say when the muses will then show themselves to be generous. Sometimes, the poem is suddenly there, and I am astounded when it lies before me. I am seldom immediately satisfied, change here and there a little, in order to leave it then usually how it was from the beginning.

FB: How does it feel to read your poems in English? Do they still feel like your poems? Is there an English-speaking poet that you admire? And how do you feel about suddenly being published in so many foreign journals?

MS: The English suits my poems very well. They sound like my poems yet also a little bit different. As if a singer were to sing the songs of someone else. Lovely is, that the older poems, due to the very good translation, have moved closer to me again. I had neglected them a little and now have read them newly again, that is a big win. That they are being published at the moment so frequently in English-language literary journals surprised me in the beginning; now it pleases me, naturally.

An English-speaking poet I admire? William Carlos Williams, as always.

_______________________________________________________________________

Read Max Sessner poems in B O D Y:

Three poems in the December 2018 issue

Two poems in the May 2018 issue

_______________________________________________________________________

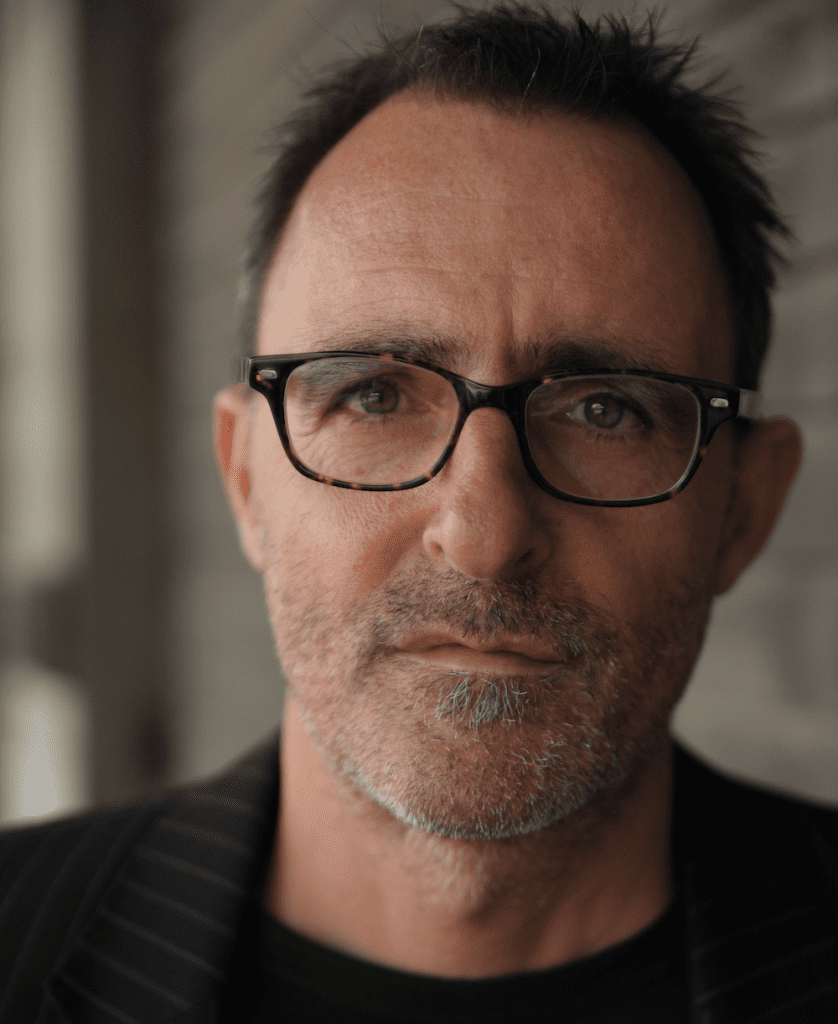

MAX SESSNER’s poems are widely published in German-language magazines, and he is the author of seven books of poetry including, most recently, Küchen und Züge (Kitchens and Trains) and Warum Gerade Heute (Why Especially Today), both from Literaturverlag Droschl. An eighth book, Das Wasser von Gestern (The Water of Yesterday), will be published by edition AZUR in 2019. Sessner’s poems, tinged simultaneously with melancholy and humor, have been described by the Nürnberger Zeitung as “singing the blues of ordinary objects.” He lives with his wife in Augsburg, Germany where he works as a bookseller.

_______________________________________________________________________

About the Interviewer:

FRANCESCA BELL’s poems appear in many journals, including B O D Y, ELLE, New Ohio Review, North American Review, Prairie Schooner, Rattle, Spillway and Tar River Review. Her work has been nominated ten times for the Pushcart Prize, and she won the 2014 Neil Postman Award for Metaphor from Rattle. Her translations from Arabic and German appear in Berkeley Poetry Review, Blue Lyra Review, Circumference, Four by Two, Laghoo, and The Massachusetts Review. She co-translated Shatha Abu Hnaish’s book of poems, A Love That Hovers Like a Bedeviling Mosquito (Dar Fadaat, 2017), and Red Hen Press will publish her first collection, Bright Stain, in 2019. She is the events coordinator of Marin Poetry Center and the former poetry editor of River Styx.