PRAGUE AND MEMORY, 2018

Editor’s Note: This is the second installment in a three-part series of a new work by American poet and critic Burt Kimmelman.

Read Part I here

Read Part III here

____________________________________________________________________

To Forget

We’re sitting around the table in our friends’ backyard, in a small town near Pardubice University where they teach (an hour’s train ride from Prague). Over lunch, our talk drifts irresistibly into the uncertain moment. Our friends are Czech citizens. She’s from this part of Bohemia. Her husband’s half Silesian, half Slovak. Czechoslovakia dissolved well over two decades ago. In an amicable divorce, Slovakia formed a nation of its own. Our friends were students then. They both had Fulbright fellowships, which took them at different times to different parts of America.

The present Czech Republic is being led by two demagogues—Zeman the President, and Andrej Babiš, his Prime Minister. Diane and I are old enough to remember violence and turmoil, most of all the tragedy of the Vietnam War—fifty thousand dead Americans overseas, at home massive unrest, bombings of draft boards, unarmed American students shot by our own soldiers at point-blank range. Now, however, we experience firsthand what it’s like to have an American President who, like Zeman and Babiš, is a demagogue.

In Prague, political demonstrations usually start on Wenceslas Square, below the statue. People then make their way across the Charles Bridge to the monumental Prague Castle. The largest ancient castle in the world, it was begun in 870. President Zeman is commonly referred to as “the Castle” (just as Trump can be “the White House”). Babiš, the Prime Minister, in the depth of his corruption, is more like Trump (except that Zeman is the coarser of the two Czech politicians). Babiš is a businessman, and a thief. He’s referred to as “the Government.”

The two of them were narrowly reinstated in office with a popular vote (but they’ve not been able to win the required parliamentary consensus, so the nation looks away). The election was a shock to many, our friends included. Older voters, remembering Communism with some fondness, helped to put these two Putin-adorers over the top. The Czechs are as bitterly divided here as we are in America.

Diane presses this fact upon our hosts, over our lovely outdoor lunch, emphasizing that the present moment is crucial, when a coalition of liberal democracies must hold together. This is especially so as the US and UK are obsessively self-involved, fixated inward. Both nations are caught up in follies they’ve created on their own, which are crippling them. They seem to be acting as if on cue, in trying to emulate “illiberal democracies” such as in nearby Hungary and Poland (the phrase comes from the Hungarian leader, Viktor Orban), whose actions have created tensions in the EU.

So we’re puzzled by our friends’ vehement objections. Yes, along with other Czechs, they feel frustrated by the German behemoth, their fellow EU member. Germany draws off their excess wealth, I’ve heard Czechs complain. Still, Diane and I are struck by how bitterly our friends talk about Emmanuel Macron, not Angela Merkel. In the news, he’s just called the Czechs “traitors,” in making reference to the recent Czech election (but is traitor a mistranslation into Czech, and then at lunch into English?).

I point out the obviously larger need for solidarity with someone like Macron, who will hold steady in the coalition against Putin. Our friends’ resentment, however, which derives from the near chaos in the daily news, has to do with France’s role in crafting the Munich Agreement. (Huh? What was that? What did she say? The Munich Agreement? But—wasn’t that eighty years ago?) Yes, Great Britain, Italy, and France, three of the four signatories to the pact, sold out the Czechs in 1938, in trying to appease Germany, the fourth signatory. Between then and now the worst conflagration humanity has ever known has occurred. In Bohemia, Moravia and Slovakia, furthermore, there have been not one but two brutal foreign occupations.

* * * *

In Europe, it’s all about history. Prague Castle was begun to be built well over a thousand years ago. Charles University, named after the great Bohemian king, was founded two and a half centuries before Jamestown was settled in what would now be called Virginia. In Europe, one is always confronted by the past—an ancient castle, a world war cemetery, a death camp.

Prague’s ancient history has its own magnetism. It co-exists with what may be a willful lack of attention to the complexities of Czech history since the demise of the First Republic with the Nazis’ takeover—which is striking, given the outsized changes in the Czechs’ lives over this span of time. The past is not a fading specter here, a disappearance into the mists of time. But if there’s an absence of recent Czech history, for a new generation, which constitutes a kind of tacit silence, that is of quite another order from, let’s say, the disappearance of the recent past as has happened in Vienna, which seems to be the one glaring exception to Europe’s wider embrace of its past. As taught in its schools, the twentieth and twenty-first centuries in Austria have seemingly been removed, especially in this city. I was told that school children may not get beyond 1916—the sunset of the Hapsburgs.

The determined ignorance of history in Prague and Vienna, respectively, is worth this comparison, above all given the two capital cities’ cultural and economic ties and rivalries over centuries, including during the years of Austro-Hungarian rule. Just over the Czech border, the quintessential European metropolis that lies at the heart of Europe, Vienna is stopped-time. Vienna is another matter altogether.

The Viennese amnesia is extraordinary. What may be unique about Vienna is that forgetting has become a national, tribal act, and this is precisely because of Austria’s past. It’s a past that has a power for Vienna, and this power has nothing to do with the force of history. The motivation to let go of the past in Austria has little to do with the post-war order. A city that lay outside the Soviet perimeter, a city of the West, Vienna nevertheless became time-out-of-mind and -memory both. The city laid down a bet on tourism, once back on its feet after the Second World War. This decision was a symptom of something deeper, however. Vienna capitalizes on Austrian amnesia, and its stopped-time is this city’s most lucrative commodity.

Here, then, post-Nazi, a city—an entire nation—stands in diametrical opposition to today’s Germany, Berlin most of all. Germany made a necessary choice for its future. Berlin remembers, wants to remember. Vienna, on the other hand, is like Disney World. It’s the theme park’s ever-present faux real. Disney World evokes an ersatz elegance and purity, like The Sound of Music. It’s the cheap version of a hollowed out aristocratic grandeur.

Vienna’s quite a comfortable city to be in, from the tourist’s perspective. Its sights are hypnotizing. A great many of them have precisely to do with its past aristocracy, and its empire. That aristocracy was magnificence as show.

* * * *

The Vienna Opera House never puts on the same opera twice in succession, even when there’s a matinée. There’s no such thing as Tosca enjoying a week’s run. Would the spell of the city existing out of time be broken? Equipment trucks proceed to and from that magnificent building, transporting old and new stage sets, in a constant loop.

This perpetual cycle of opera productions happens to be a legacy of the Hapsburgs whose practice was to demolish all surrounding buildings within the area now referred to as the Ring, then to rebuild them. The cycle ran every third or fourth generation. In this manner—this planned, recurrent, destruction and rebuilding—the Hapsburgs let the world know how wealthy they were, therefore how powerful. Vienna’s Ringstrasse was once a wall circling the great palaces and other like splendors. What’s left inside the Ring today are the uncommon artifacts, along with the stories they tell, of the Imperial household. The objects show how the family lived and ruled.

The Sisi museum tells the tale of the last Empress. The tale’s a tragic one—operatic, actually. It goes like this: From age sixteen, she found herself trapped playing the role of a living relic. An outsider to the family, she was left powerless, not even allowed to raise her own children; decisions were made by their grandmother, her mother-in-law. Sisi turned to writing poetry, in gilded isolation. The maudlin tease, as her life is presented, each stop along a winding route in what was the household, is whether the poetry being replicated in the exhibition discloses Sisi’s descent not merely into grief but madness as well.

The Jewish Museum, located in another part of town, is a bit of a contrast—and its Annex too, in yet another neighborhood. It’s as if it has been sequestered within the large city, although the siting of it was dictated by the fact that the Annex is mostly dedicated to displaying and explaining recently discovered ruins of Vienna’s medieval Jewish ghetto. (You can examine them after descending some stairs.) On the other hand, the Annex building is so completely non-descript, on the outside, as to be unrecognizable. It’s not easy to find even when standing in the Judenplatz, looking all around. Inside, an armed guard is positioned near the ticket desk, in civilian garb, wearing a yarmulke.

There’s but one memorial to the Holocaust in Vienna. Enigmatic but fine-looking and powerful, it yields its secret slowly. It’s in another plaza. At the core of the monument is a sculpture of an elderly Jewish man on his knees, scrubbing the street with a brush. The figure is dwarfed within a complex of monolithic slabs of stone.

Nazism was alive and well in Austria. Nazi ideology was robustly nurtured in Vienna. Children were enrolled in youth corps and remained zealous Nazis for their entire lives, as members of various ideological organizations. Nazi party membership was proportionately quite sizeable. The presiding American General during the post-war occupation, Mark Clark, once he realized how deeply rooted and widespread Nazism had been there, scaled back his denazification program in order to be able to govern.

Arriving in Vienna, you find yourself in a gleaming, well functioning, modern city. In its confection of high-tech glamour and old-world reliquary, Vienna sells forgetfulness, although it depends on the historical to supply context and as a predicate for the city’s bad faith. Any museum frames the past, holding it in a stasis. Vienna’s museums, however, the past seemingly alive, keeps it in confinement.

To Remember

Yet Europe is contrary to Austria, as well as to the United States. Caught in the throes of its past, Europe in large draws strength from it, perhaps Germany most of all. The European Union’s raison d’etre is European history. Its mandate to reengineer European economies, hence Europe’s politics, is an attempt to avoid further internecine war. The EU, however, the greatest experiment of all, is unavoidably and stupendously clumsy in its administration from Brussels—so its half-billion inhabitants have come to feel, perhaps fatally, distant and detached from it. The design of the Union was meant to overcome this. It may not.

Meanwhile, Germany is doing exceedingly well within the EU, the largest of the Union’s economies. Germany faces challenges that were invented by the Germans themselves, on the other hand. What could Merkel have done but to welcome so many refugees since 2015, given Germany’s Nazi past? The Czech Republic, in comparison, has let in eleven people. It simply ignores EU rules! Some countries—Hungary, spectacularly, has fenced its borders—are especially defying the EU on immigration.

Austria has taken in refugees in number equivalent to one percent of its population. Of late it has filed for an exemption. The new Austrian Prime Minister is pushing for hard external borders in Europe—regardless of any problems that might arise for countries like Italy and Greece—in his striving to appease anti-immigrant hardliners as well as people like Merkel who embrace the progressive European idea of tolerance and an open society. The difference between Austria and Germany—between Vienna and Berlin, two cities on opposite trajectories—is stark.

* * * *

Diane and I could not avoid comparing Berlin, when we were there, with both Prague and New York. Berlin offers a very different kind of life than is to be had in Prague. I was seated on a Prague tram one late afternoon; across from me was a woman who was being a man. Dressed in bomber jacket, jeans and heavy leather boots, she reached into her canvas courier bag to pull out, of all things, a book of George Perec’s poems, which had been translated into Czech. What a rare delight!

We came to a stop in the busier commercial part of town; it was the rush hour. Lots of people got on, business types who were tired and eager to get home. A woman in a business suit, seeing my companion dressed in what the woman must have felt was a man’s clothes, openly glared at her. I was taken aback—especially because people in Prague, at least in public, maintain a cordiality—even as I had already come to realize that gay people in Prague keep almost entirely undercover.

It’s rare to see a gay couple strolling along as “gay” on a Prague street. Arriving in Berlin’s Hautbanhof, we sensed the city’s élan. We made our way to the station’s information office where we sorted through various pamphlets and guides, and came across a listing of the upcoming week’s “queer” happenings.

Berlin is inspiring. It’s a big cosmopolitan city. Unlike New York, it’s very green; a third of its area is parkland. It’s geographically much larger than Prague and has three times Prague’s population of a million. The trees, grass and birds have a calming effect. Everything works in Berlin (everything works in Prague too), and the sense of order—regardless of the fact that most of the city was rebuilt after the war—is part of the city’s experience.

Visually Berlin lacks the beauty, the imagination, of Prague. I don’t think the Germans are capable of designing beautiful cityscapes. I wonder if they ever were. But what a city! Berlin’s alive. It reminded us of New York although without New York’s massive, unrelenting energy and density. London also seems like New York but in another way. (Paris, Rome, other cities don’t, can’t.) London is a broad mix of people, which gives it a vitality. It’s reminiscent of New York, in any case, most of all, because of a sense that the city’s out of control.

Not so Berlin—and this is a reason to fall in love with it. Yet order, I think, can preclude soaring beauty. Prague is coherent, orderly—witness the Bohemians’ exquisite aesthetics, on the other hand (even at this moment when much of Prague’s infrastructure is in the process of change). Regardless of the great German painting as well as the forward-looking architectural movements in times past, is it really true that Berlin is now the center of the art world? Does Berlin’s reputation depend on the work of breakthrough artists who were part of the German generation growing up in the war, such as Gerhard Richter?

Berlin does welcome art and architecture great in imagination and sympathy, though. I think particularly of Daniel Liebeskind’s design of Berlin’s Jewish Museum. Simply being in it for any length of time, the museum becomes a sacred space. That’s in great measure because of Liebeskind’s architectural genius—the look, feel, dimensions of the rooms, for instance, the means of getting around within the building. The curation is to be admired as well. The photos and artifacts presented include everyday objects and letters, informational texts, and art works. But they’ve been kept to a minimum.

They’re presented within rooms and passages of various arrangements. The consequent elegance of memory foregrounds the Holocaust. The history is overwhelmingly powerful. Beauty and loss suffuse everything and everyone there, inside the building and in the garden beyond it. Such a museum, in Berlin, was what was needed.

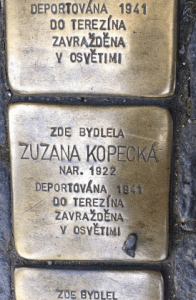

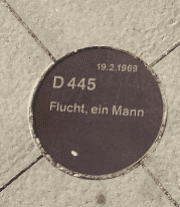

Unlike in Vienna, memorials to the Holocaust are ubiquitous in Berlin. In Prague, we’d discovered brass plaques embedded in sidewalks, meant to keep alive the memory of people who were taken from their homes, ultimately to their deaths during the Nazi years and thereafter. These people lived where the plaques have been set. We noticed these plaques in Berlin too. They’re of the same size and composition, and also embedded in sidewalks.

Memorial to an anonymous escape from East Berlin.

Memorial to an anonymous escape from East Berlin.Very many of them remember people who attempted escape from the eastern part of the city, most of them after the Berlin Wall was constructed, a plaque’s location marking the place of escape, at the precise crossing points. Some of these people didn’t succeed. The plaques document both the failed and successful escapes from East Berlin. They provide, when known, a name, otherwise a description (so-and-so wearing a tan overcoat and hat), or when not known then, simply, “ein Mann” (“a man”), and the date the escape was attempted.

* * * *

The Berlin Wall itself still stands in some parts of Berlin—in order to remember. At the East Side Gallery, an open-air affair, the murals and graffiti on the Wall left standing in that part of the city are a contrast to the plain slabs left up near where The Wall Museum has been sited. Further along the avenue there, only the steel struts of the Wall have been allowed to remain. In one spot they border a grassy field containing photos and captions.

The Wall Museum proper houses compelling, sweeping presentations in a variety of mediums (in such abundance we had to return a second day to take in most of what was on display). Many stories of individual people are told, in an attempt to lend some understanding of their lives, and generally the lives of everyone who was caught in the divided city as the greater Cold War developed.

There are few casual visitors to The Wall Museum, and the mood inside is sober. There are historical films and photos, along with audio or video recordings, many made in more recent times by survivors. There are other historical artifacts, prominent among them newspaper accounts. The story of the Wall, how the idea of it took shape, the circumstances leading up to its construction, and how people in both East and West Berlin came to cope with it, is told poignantly, in detail and with stunning clarity.

We visited the Stasi Museum. We knew some of the Stasi history yet we hadn’t grasped the depth of government insinuation into every facet and moment of people’s lives. East Germany, as a surveillance state, surpassed all other nations. What was achieved there was shocking when we considered the situation up close, as we came to realize what was at stake for the Berliners. In East Germany everyone spied on everyone else.

One bit of especially revealing footage at the Wall Museum shows an ordinary moment that turned weird, quite extraordinary, in seconds. At the same time, what unfolded was completely understandable. An East German soldier was standing guard as laborers were first building the Wall. They were troweling cement, and the wall was rising in small increments. In the film, you see that West Berlin was achingly within reach for these people, visible only feet away.

People were going about their lives there, right before the East Germans’ eyes. The difference in quality of living between East and West Berlin was already plain to all. In a split second, as a tram was coming along on the Western side, stopping to pick up passengers, the soldier guarding the workers made his break, still with his bayonetted rifle in hand, hurtling over the concrete blocks and cement not yet dried. He didn’t have far to run. The tram driver waited until he got inside before pulling away.

Our apartment in Berlin was a block from the dividing line. On Sunday, we strolled through Mauer Park (mauer, wall). The day was sunny until everyone fled in a sudden torrent. The festive, ad hoc ambience in the park, before we got rained out, reminded me of the sixties in New York and San Francisco, where young people enjoyed violating the norms of the time—the Be-Ins and Smoke-Ins. We had hope for a future we’d help to create.

Now, in Mauer Park, Diane and I were enjoying the weekly karaoke assemblage, seated in an amphitheater. There were about fifteen performances before the weather turned. Only one of them was by a native German. People have come to Berlin from all over the world. Most of them in the park that Sunday are now living there. The event was run by a couple of Irish guys who were on a European karaoke circuit. With their sound equipment, they’d arrived in Berlin that morning.

* * * *

Like everywhere in Europe, Berlin’s wars, its holocausts, are never far from one’s awareness. Germany has devoted itself to memory and bearing responsibility. (German school children make the journey to Auschwitz.) In return, the city is diverse, alive. There’s a warmth people in Prague normally extend to others, which I didn’t find in either Vienna or Berlin. Yet in Berlin there’s a lifting spirit of laissez-faire, which is so very necessary right now.

Berlin’s at a crossroads. I don’t think New York is, while it should be. Dear Praha’s found its new direction. The city’s filled with the offices of multinational corporations. English is everywhere, to be seen and heard. That includes lots of mixed Czech and English phrasing, or sometimes just straight-ahead English. Scrawled on a wall near the entrance to a Prague metro station: “Graffiti saved my life.”

The English graffiti is an artifact of American cultural hegemony. I make this stipulation while sitting in a restaurant named Hamburg, a block from our apartment in Holešovice, a Prague neighborhood recently become artsy and increasingly gentrified. Michael Jackson’s singing is being pumped through the bar’s sound system.

It seemed like everyone in Berlin spoke idiomatic English. German and English are similar, of course, while Czech and English have nothing to do with one another. Czech attempts at the American idiom are sometimes strange. This may have as much or more to do with cultural miscues.

In a small Czech town we saw a baseball cap on the head of a ten-year old boy, on the front of the cap the phrase “extreme obscene.” In Pilsen, kitty corner to the main square, there’s a big sneaker store named “Snow Bitch,” which earned a second turn of our heads. When we asked one of Diane’s students, who lives in Pilsen, about it, she simply said that people didn’t really know what was wrong with it, but anyway that wasn’t the point.

The Czech Republic is an old-world society that was paved over by Communist historical, artistic and architectural revisionism. Then that was supplanted by post Cold-War Capitalism and all that it conveys, and now by the multinational and high-technology version of it. I’ve had the thought more than once that, if Brexit actually happens, Prague could attract some of the financial services and other aspects of the digitally sophisticated economy that can no longer thrive in London, thus challenging Paris and Frankfurt.

There’s more English in the center of Prague to be heard and seen than German, Russian, Ukrainian and Polish combined. (Sizable minority populations of Roma, and Vietnamese, their language-flows, weave through Prague on their own.) But in Berlin everyone speaks really good English. It’s difficult to avoid marveling over how World War II and then the Cold War made Germany what it has become.

Berlin’s truly an international city. Indeed it’s on a par with a city like New York in a number of ways, or London, both larger in population. In the liberal democracies’ present struggle for survival, along with Paris Berlin is key. Berlin’s earned its seat at the big table for many reasons.

I suppose this city’s geo-political cachet may call for, in some people’s minds, the city’s emotionless buildings. The remnants outlasting the war’s saturated aerial bombardments, such as the remaining portion of the Brandenburg Gate, seem to me beset by gravity. This may have been the point. No one is as efficient as the Germans. But again, I don’t think the Germans have it in them to create visual beauty with the brilliance and verve of the Czechs.

I can’t help but think that some of Prague’s cultural authority, which in times past could have been felt abroad, such as in Vienna, has to do with the city’s utter beauty, certainly rivaling the Austrian capital among other Central European societies. Not just the old Prague, now—what city, other than Prague, displays postmodern architecture as undulation, as well as in juxtaposition to the elegant, graceful older buildings and streetscapes? Most of the new, snazzy high rises are far enough from the old city to avoid such association.

What’s known as the Dancing House is another matter. The classically beautiful older building had to be modified due to a mistaken aerial bombing during the war (Prague didn’t suffer other such attacks). The building was reconceived as a conscious amalgam of old and new, one or the other creating its motif, depending on where you stand, from where you look. The building’s both swervy and understatedly straight up.

But the Dancing House, which had been an effort to restore an older structure partially destroyed by the bombing, was the product of Bohemian wit (albeit Frank Gehry also worked on it), and it may have planted the seed that has led to recently constructed high rises in other parts of town. Prague as city, taken whole, could be headed toward an aesthetic unity that would comport with the multinational system. The newer—they could be called irreverent—tall buildings (such as in the Holešovice and Karlín districts) are the consequence of this multinational, corporate, economic order that looks to be absorbing Prague—while allowing the older “classical” urban scapes to hold onto the city’s memory. It’s an intact history if only because of the tourist trade.

There are major infrastructure projects, on the grand scale, underway. They likely could not have gotten going were it not for EU “catch-up” funding, which has been dispensed to the newer members. The Czechs seem to be using it well. Although people in Prague have mentioned a level of corruption that prolongs the time-to-completion of these projects, there’s a new water tunnel being constructed, visibly progressing, and new highways.

Yet Berlin is really cosmopolitan. Prague is visually stunning in a way neither New York nor London can ever hope to be. Maybe in theory Berlin’s architecture could have been so, a city more on a scale with Prague. In any case, Berlin is open and free in ways these other cities should be. Berlin’s human embrace is astonishing. The city is rich; at the same time it’s comfortable, and welcoming.

Freedom, in Prague, is often expressed only through codes of body language and speech that were bred during the totalitarian half-century (if not earlier) subsequent to the First Republic. People in Prague are heartfelt but watchful. Tentative, simultaneously full of hope, they look for the right signals.

No city can stand comparison with Prague. Some of that has to do with the geography—the meandering Vltava River and the hills rising up sharply from it. Berlin, nevertheless, so very green—trees and birds ever present, enveloping you in the warm months—has its rivers. They too create an urban ambiance.

* * * *

And then there’s Russia. On the morning the news broke, in Berlin, that Trump had refused to sign the G7 joint statement, Diane and I were breakfasting at an outdoor café a block from Mauer Park. I noticed a German couple at the next table. They were grimly smiling at the widely circulated photo of Merkel with her fists on a table as she confronted Trump, leaning into him, looking into his face, as he sat across from her and the other G7 leaders with his arms folded in front of him. The photo was featured on the front page of the German newspapers. (People in Berlin still read newspapers.) These Berliners were proud of their leader. And they were waiting to see what would come of both Germany—as Merkel faced a challenge from the right—and liberal democracy.

At our garden lunch near Pardubice, our Czech friends could well understand what the Poles may be thinking. Poland shares a border with Russia. No one at lunch wished to offer a fig leaf for the burgeoning fascism in today’s Poland (the Poles, finally, have been cited by Brussels for their government’s new anti-democratic laws, which were instituted in the face of EU standards and expectations) or for that matter the naked fascism in Hungary, and as may develop in Austria and Italy—except for Tomáš’s rejoinder that the Poles suffered terribly under the Nazis.

In the meanwhile, we all worry about the Czech Republic. Will it continue to veer rightward? It’s a prosperous country, with very low unemployment. It has the highest per capita car ownership in Europe. It enjoys the lowest infant mortality rate in the world. Children in Prague are being parented well, with fathers also intimately engaged in the kids’ lives.

Prague’s businessman-prime minister realizes how important it is to stay within the EU. It’s just that the Czech Republic is merely along for the ride. With a total aggregate of ten million people (the Poles are four times as many), the Czech Republic is a bit player.

____________________________________________________________________

Read Part I here

Read Part III here

____________________________________________________________________

BURT KIMMELMAN has published seventeen books of poetry and criticism, and more than a hundred articles on literature, art and other matters. His poems are often anthologized and have been featured on National Public Radio (in the United States). Interviews of him are available in print or online. His ninth collection of poems, Abandoned Angel (Marsh Hawk Press), appeared in 2015. A new collection, Wings Apart, is due to be published by Dos Madres Press next year. He teaches literary and cultural studies at New Jersey Institute of Technology. More about him can be found at BurtKimmelman.com.

____________________________________________________________________

Read more by Burt Kimmelman:

Three poems at B O D Y